Many companies are grappling with disruption. Today, new and relentless competitors with more money, more people, and more advanced technology appear seemingly out of nowhere, attempting to grab customers and gain market share.

Companies serious about dealing with this threat (which some describe as “existential to their survival”) have mobilized their entire corporation to come up with new solutions. This isn’t a small undertaking, because threats are coming from multiple areas in multiple dimensions. Incumbents must consider, for example: How do they embrace new technologies? How do they convert existing manufacturing plants (and their workforce) to integrate a completely new set of technologies? How do they bring on new supply chains? How do they become present on new social media and communications channels? How do they connect with a new generation of customers who have no brand loyalty? How do they use the new distribution channels competitors have adopted? How do they make these transitions without alienating and losing their existing customers, distribution channels, and partners? And how do they motivate their most important asset — their people — to operate with speed, urgency, and passion?

Quite often time is short — companies have just a handful of years to solve these problems before their decline becomes irreversible. Current best practices have companies organize formal corporate-wide initiatives to out-innovate their new disruptors and fight the tidal wave of creative destruction engulfing their industry. But to succeed, companies realize this isn’t simply coming up with one new product. It means pivoting an entire company and its culture: the scale of solutions needed to dwarf anything a single startup would be working on.

Leaders should start by identifying critical areas of change across the enterprise, then setting up action groups and subgroups with people from across the company: engineering, manufacturing, market analysis and collection, distribution channels, and sales. This should even include close partners. A large corporation that is “dealing with disruption initiative” could have a thousand more working on the projects in offices scattered across the globe.

After recently observing one such corporate initiative, I have developed some suggestions for how they can be improved.

Are these the real problems?

As with many of the innovation initiatives I have seen, this effort seemed to be well organized. Topic areas to be addressed and solved came from the company’s corporate strategy group, and the people who generated these topic area requirements offered the action teams their advice. The company also created a transition team to facilitate the delivery of the products from these topic action teams into production and sales.

However, I noticed that often, several of the requirements from corporate strategy seemed to be priorities given to them from others (“Here are the problems the CFO or CEO or board thinks we ought to work on”) and/or were from subject matter experts (“I’m the expert in this field. No need to talk to anyone else; here’s what we need”). It appeared the corporate strategy group was delivering problems as fixed requirements, for example, to deliver these specific features and functions the solution ought to provide.

Here was a major effort involving lots of people but missing the chance to get the root cause of the problems.

Clearly, some requirements were known and immutable. However, when all of the requirements are handed to the action teams this way, the assumption is that the problems have been validated, and the teams do not need to do any further exploration of the problem space themselves.

Those tight bounds on requirements constrain the ability of the topic area action teams to:

- Deeply understand the problems — who are the customers, internal stakeholders (sales, other departments), and beneficiaries (shareholders, etc.)? How do you adjudicate between them, priority of the solution, timing of the solutions, minimum feature set, dependencies, etc.

- Figure out whether the problem is a symptom of something more important

- Understand whether the problem is immediately solvable, requires multiple minimum viable products to test several solutions, or needs more R&D

I noticed that with all the requirements fixed upfront, instead of having the freedom to innovate, the topic area action teams had become extensions of existing product development groups. They were getting trapped into existing mindsets and were likely producing far less than they were capable of. This is a common mistake corporate innovation teams tend to make.

When team members get out of their buildings and comfort zones, and directly talk to, observe, and interact with the customers, stakeholders, and beneficiaries, it allows them to be agile, and the solutions they deliver will be needed, timely, relevant, and take less time and resources to develop. It’s the difference between admiring a problem and solving one.

Having all fixed requirements is a symptom of something else more interesting — how the topic leads and team members were organized. From where I sat, it seemed there was a lack of a common framework and process.

Give the Topic Areas a Common Framework

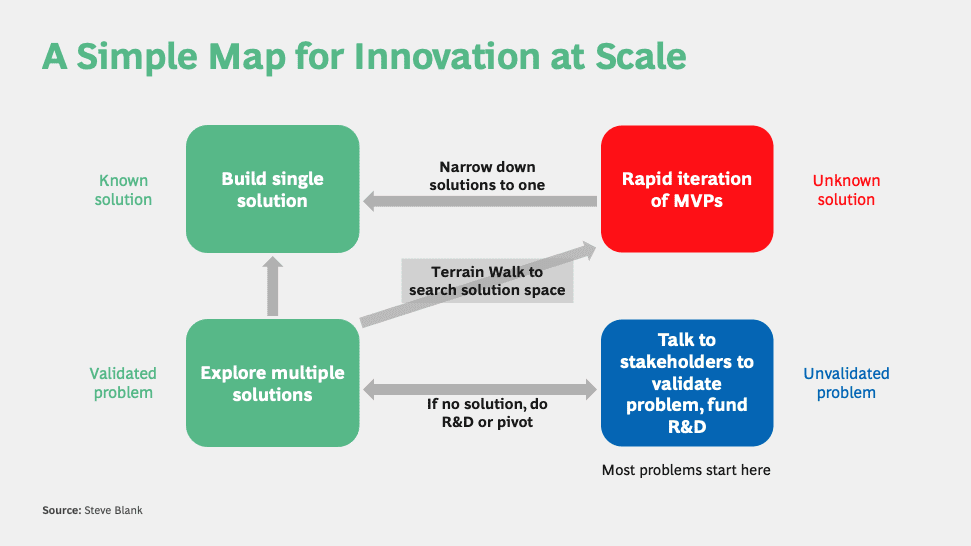

What would help these “dealing with disruption initiatives” is giving the topic action team leaders and their team members a simple conceptual framework (one picture) and common language. This would allow the teams to know when and how to “ideate” and incorporate innovative ideas that accelerate better outcomes. The framework would use the initial corporate strategy requirements as a starting point rather than as a fixed destination.

A simple chart (see diagram) explains that most problems start in the bottom right box. These are “unvalidated” problems. Teams would use a customer discovery process to validate them. (At times some problems might require more R&D before they can be solved.) Once the problems are validated, teams move to the box on the bottom left and explore multiple solutions. Both boxes on the bottom are where ideation and innovation-type of problem/solution brainstorming are critical.

If a solution is found and solves the problem, the team heads up to the box on the top left.

Very often the solution is unknown. In that case, think about having the teams do a “technical terrain walk.” This is the process of describing the problem to multiple sources (vendors, internal developers, and other internal programs), debriefing them on the sum of what was found. The terrain walk could reveal that the problem is a symptom of another problem or that some of the sources see it as a different version of the problem — or that an existing solution already exists or can be modified to fit.

But often, no existing solution exists. In this case, teams could head to the box on the top right and build minimal viable products (MVPs) — the smallest feature set to test with customers and partners. This MVP testing often results in new learnings from the customers/beneficiaries/stakeholders; for example, they may tell the topic developer that the first 20% of the deliverable is “good enough” or the problem has changed, or the timing has changed, or it needs to be compatible with something else, etc. Finally, when a solution is wanted by customers/beneficiaries/stakeholders and is technically feasible, then the teams move to the box on the top left.

The result of this would be teams rapidly iterating to deliver solutions wanted and needed by customers within the limited time the company has left.

Creative destruction

Creative destruction — where the old replaces the new — is inevitable in any industry, it’s only a matter of when.Few companies make the transition.

Those that make it do so with an integrated effort of inspired and visionary leadership, motivated people, innovative products, and relentless execution and passion.

Lessons Learned

- Creative destruction and disruption will happen to every company. How will you respond?

- Topic action teams need to deeply understand the problems as the customer understands them, not just what the corporate strategy requirements dictate. This can’t be done without talking directly to the customers, internal stakeholders, and partners.

- Consider if the corporate strategy team should act more as facilitators than as gatekeepers.

- A light-weight way to keep topic teams in sync with corporate strategy is to offer a common innovation language and problem and solution framework.