Business is built on collaboration. Working together with others toward a common goal has many obvious advantages: it enables dividing and conquering complex tasks, bringing diverse perspectives to a problem, reducing burnout, and increasing motivation and happiness. Because of this, as Michael Watkins put it, teaming and collaboration are “seen as the workplace equivalent of motherhood and apple pie—invariably good.”

In recent years, our ability to collaborate anytime and anywhere has skyrocketed; we meet 60% more today than we did before the pandemic. So, if collaboration is like apple pie, shouldn’t this increase in collaboration result in better outcomes for businesses? Our research suggests that the answer is sometimes—but that it can also be a hindrance. Given the strengths and limitations of collaboration, leaders need to foster a more balanced and productive approach. They can do so with an understanding of when collaboration is the right choice—and when it makes sense to look for alternatives.

Why collaboration is more like a hammer than apple pie

Previous research has found that collaboration takes time and energy, produces stress, requires significant logistical coordination, and can result in “collaboration overload.” But our hesitation to recommend collaboration as a default way of engaging doesn’t stem from these costs or risks—rather from the fact that collaboration simply isn’t always the best tool to achieve the primary goal for which business leaders use it: developing ideas and solutions to problems.

It’s well-known that corporate hierarchies can inhibit employees from sharing their ideas. But psychologists have also shown that, even when there aren’t issues of power in play, groups tend only to discuss information they have in common rather than share their unique insights. This means that collaboration doesn’t effectively enable the collaborators to pool their information or ideas.

Collaboration can also cause groups to dismiss good ideas too quickly. The larger a group is, the more likely it will be to converge on a set of views and be too fast to dismiss novel or disruptive ideas that don’t align with the consensus. As philosopher Kevin Zollman showed, collaboration can even cause groups to investigate ideas less thoroughly and converge too quickly on wrong answers.

These factors can have significant impacts: A study by researchers Lingfei Wu, Dashun Wang, and James A. Evans looked at more than 65 million scientific articles, patents, and software projects and found that large collaborative teams are less likely to advance innovative or disruptive ideas than smaller teams. Collaboration causing groups to become cognitively homogenous and overlook good ideas is also believed to explain why the board of Swissair continued investing in failing airlines, which eventually led to its grounding in 2001; why Blockbuster’s board laughed Netflix out of the room in 2000; and why Kodak was so slow to embrace digital photography, despite being a pioneer of the technology.

Our claim is not that businesses should give up on collaboration. Collaboration is an organizational tool that’s good for many purposes. But it’s not always the best tool if the goal is innovating, disrupting, exploring the space of new ideas, or deeply developing those ideas. Like any other tool, leaders must think carefully about when it makes sense to use it—and when it doesn’t.

Choosing the right model

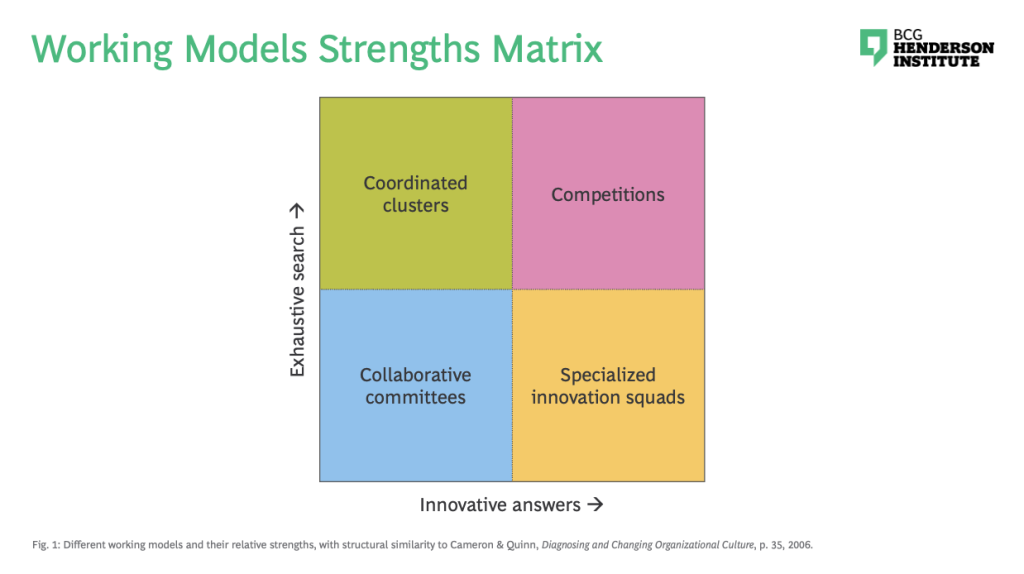

When faced with a decision about how to organize a group to solve a problem or generate ideas, there are two crucial factors to consider: innovation (how innovative or disruptive, rather than incremental, do the outputs need to be?) and exhaustiveness (how important is it for the group to explore all possible solutions to ensure that the absolute best output is discovered and developed?). If we plot the two factors on a matrix, four broad group working models emerge.

- Collaborative committees: In 1982, when then Johnson & Johnson chairman James Burke heard the news that poisoned Tylenol was being distributed in Chicago, his top priority was to find a safe, low-risk solution quickly. Collaborative teams and committees are effective at helping to incrementally advance thinking in cases where innovative solutions and costly exhaustive searches either aren’t needed or are impossible. They’re also good at getting buy-in from the group and can be used to make fast decisions. It made sense, then, that Burke’s first step was to form a strategy team, which immediately took steps to warn consumers and eventually order a national recall. The collaboration worked, and Tylenol is still one of the most popular pain relievers in the market.

- Competitions: In 2006, Netflix sought ways to improve its recommendation algorithm. To do this, the company launched a public competition, in which individuals and teams from around the world competed over a $1M prize for the top submission. Competitions work well for situations like these, where both innovation and exhaustive exploration are needed. The prize incentivizes many teams to participate, each searching different parts of the space of possible answers and bringing their own distinct ideas—and it encourages teams to develop innovative approaches to beat the other teams. For Netflix, the competition worked: The winning algorithm was twice as good at producing recommendations as their previous one. Paypal and L’Oréal also both use Shark Tank–like internal competitions to get innovative ideas in front of senior management without the risk of exposing confidential information to the public.

- Specialized innovation squads: When firms need innovative or disruptive ideas, the above research from Wu, Wang, and Evans shows that small teams are the best bet. In these cases, we recommend the use of small, specialized innovation squads (in the range of 3 to 4 team members). Amazon, for example, attributes many of its innovative market disruptions to its use of small teams like these, and even has a two-pizza rule that limits teams to a size that can be fed by two pizzas. Because of their size, innovation squads can’t be expected to exhaustively search a large space of options. But small teams are more likely to develop innovative ideas, and they have other virtues, including requiring less coordination and resources and increasing employee satisfaction.

- Coordinated clusters: In cases where exhaustively exploring the options is the top priority, collections of small teams can be expected to perform better than a single large team—as long as there is a coordinating body to divide the options among the small teams and ensure evaluations happen in comparable ways. Unlike competitions, because a coordinating body sets the agenda of options to be explored, coordinated clusters are less likely to come up with truly outside the box innovative ideas. But, for the same reason, coordinated clusters can be expected to more thoroughly explore a given agenda of options—and to do so more quickly. Google, for example, is well-known for using different teams to test new products, and Amazon is using this approach to test new last-mile delivery options (Prime Air drone delivery, Scout autonomous robot delivery, and its Delivery Service Partner program). Using coordinated clusters isn’t about ensuring each cluster’s idea is good; rather, it is to test multiple ideas in parallel to explore what’s possible.

Of course, the demands of some projects might not neatly fit into this simple framework. When that happens, modifications and hybrids of these four broad working models might help. Consider, for example, corporate strategy. Major strategy decisions are typically made by large committees involving a significant portion of the C-suite. A benefit of this traditional approach is that it’s more likely to generate broad buy-in.

But for innovation and exhaustive exploration of strategy options, a hybrid, two-step process might work better: First, use small strategy discovery teams to explore the space of possibilities, either competitively or in a coordinated way. Then task a larger collaborative group (likely involving top management) to evaluate the proposals and decide which to pursue. The first step of this hybrid approach uses the innovation and investigation powers of smaller, less-collaborative teams to flesh out the ideas, and the second generates the buy-in needed for strategic decisions.

How to set up your organization to work more, or less, collaboratively

To harness the potential of this framework, your organization needs the talent, incentive structures, support systems, and culture to both enable the working models that make sense for your organization and switch with agility among them as needed. Most organizations will need to make the following three changes:

- Invest in the right balance of collaborative talent

Leaders tend to focus their talent strategies on T-shaped talent—employees who have both deep expertise and sufficient general knowledge to collaborate across the organization. This assumes, of course, that the organization needs everyone to prioritize collaboration, which may or may not be true in a particular case. Instead, businesses should foster the mix of collaboration-oriented (T-shaped) and less-collaboration-oriented talent that works best for them.For many companies, a balance of T-shaped and more content-focused expert talent will enable a healthy mix of collaboration and other working models. But, if a company more highly values innovation and disruption, it might make sense to focus on more independently-minded expert talent—those you might typically associate with start-ups—who can maximize the value they produce as individual contributors.

- Develop a culture that sees collaboration as one among several viable approaches

To take full advantage of a mix of both more and less collaborative working models, an organization must view collaboration as just one among many organizational tools—one that’s good for some purposes but not others. For example, common actions like adding one more person to a team or prompting two teams to collaborate should be recognized as things that can create positive or negative effects, depending on the context.Leaders can set the tone, but they will need support systems to enable and sustain the mind-set shift. For example, leaders can establish a “competition support unit” and a “teaming team” to teach and consult on best practices for structuring teams. And when collaboration is needed, leaders can foster a culture that embeds some of the innovation, disruption, and investigative powers of less collaborative groups, for example, by normalizing the use of “idea advocates” in meetings to ensure views are not prematurely dismissed.

- Establish systems and incentive structures to support the right balance of collaboration

Incentivizing the right balance of collaboration involves training team leaders and evaluating them on their working model choices, and where possible, embedding default team working models into business processes. Once the teams are set up, they’ll need collaboration tools that support their working model, too. Perhaps counterintuitively, to promote innovation and exploration, the tools might be set up to limit access to internal knowledge libraries for some teams to prevent them from falling into established approaches and ideas. Similarly, to facilitate independent work, internal communication tools can prompt employees to avoid discussing team content with other teams.

Leaders often default to collaboration when thinking about how teams should work, so for many, it will be a big shift to think of collaboration as just one tool in the organizational toolbox. But this shift is critical: To maximize advantage, leaders should consider the context and team goal before deciding how a team will work.