Summary

Strategy needs to be tailored not only to the moves of competitors but also to the sources of competitive advantage, which shift over time — resulting in different eras of competition. Being well-positioned in one era does not guarantee success in the subsequent one.

The next era of competition will be characterized not only by continued rapid change and high uncertainty, requiring ongoing renewal to sustain performance but also by tighter constraints on resources, including capital. Coupled with rising investor desire for short-term profitability, this will make it both harder and more necessary than ever for firms to simultaneously execute their current business model and search for new sources of advantage — to be ambidextrous.

Breaking the inherent trade-off between search and execution will require new approaches. We describe one such approach, “co-ambidexterity,” which interweaves firms’ and customers’ search and execution processes.

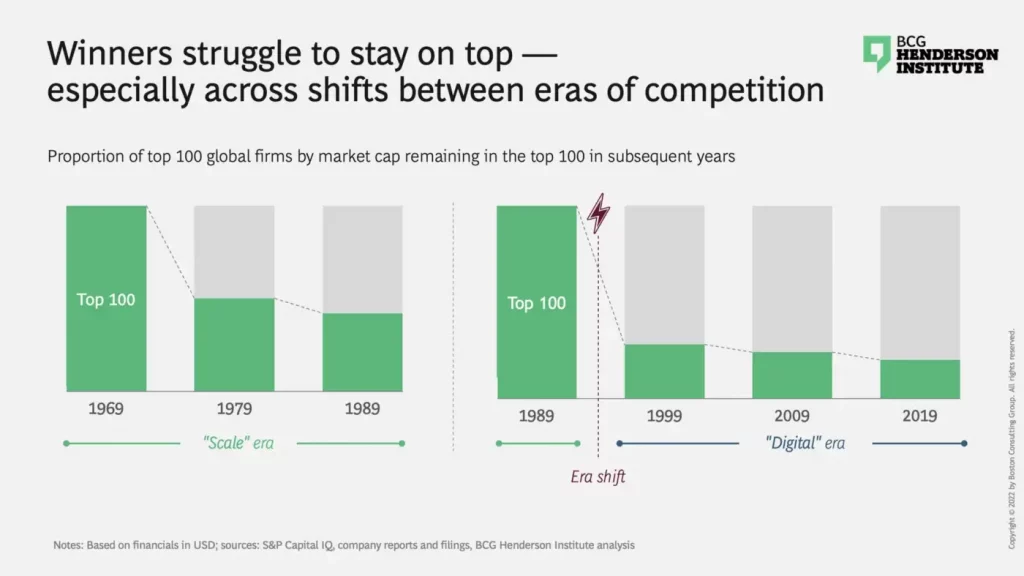

“Nothing wilts faster than laurels that have been rested upon,” wrote English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. He may not have had a competitive advantage in mind, but the idea translates perfectly to business: Even the world’s most successful firms struggle to stay on top, as competition and change eventually erode their advantages. For example, of the world’s 100 most valuable firms in 1969, only half remained in the top 100 a decade later. The pace of this drop-off has since accelerated, with a mere 28% of the top 100 in 1989 remaining 10 years hence. What changed?

Distinct eras of competition

Our research indicates that the basis of competition shifts over time, creating distinct eras, with winners finding it much hard to sustain outperformance across era shifts. As a result, competitive decay is faster across than within eras (see exhibit 1) — as was the case with the onset of the digital revolution, which began in earnest in the early 1990s.

Underlying this phenomenon is the fact that, as sources of competitive advantage shift, so do the skills required to win.

Prior to 1990, competition was largely a game of physical scale, which was capital- and time-intensive to replicate, creating an effective barrier to entry. Driving this scale advantage was the “experience curve” effect, which Bruce Henderson and colleagues codified after observing a reduction in unit production costs as cumulative volume increased, which resulted in a strong correlation between competitive profitability and market share. To be successful in this era of competition, firms needed primarily to be skilled at building scale and defending their market share by efficiently executing their business models.

The digital revolution radically changed the nature of competition. By building or leveraging digital platforms that connected suppliers and consumers, small start-ups became able to extract rents as ecosystem orchestrators, such as Airbnb, or contributors, such as Adyen. Thus, physical scale lost its role as the key driver of advantage. Indeed, it even became a hindrance, a source of inertia in dealing with rapidly evolving technologies and the business models that exploited them. At the same time, low costs of capital, as reflected in the Fed Funds rate, fell from an average 10% in the 1980s to an average 3% in the 2000s, while hovering near 0% throughout the 2010s. This meant that new entrants could relatively easily obtain financing to quickly scale new solutions. Thus, traditional barriers to entry were eroded and incumbents were less able to defend their historic sources of advantage. This created the “digital era,” in which constant disruption was the norm. As a result, 5 of the world’s 20 most valuable companies today (and 10 of the top 50) were founded after 1989. These new winners, born and bred in the digital era, disrupted scale-era champions that found it hard to adapt to the new context.

Changing capabilities between eras

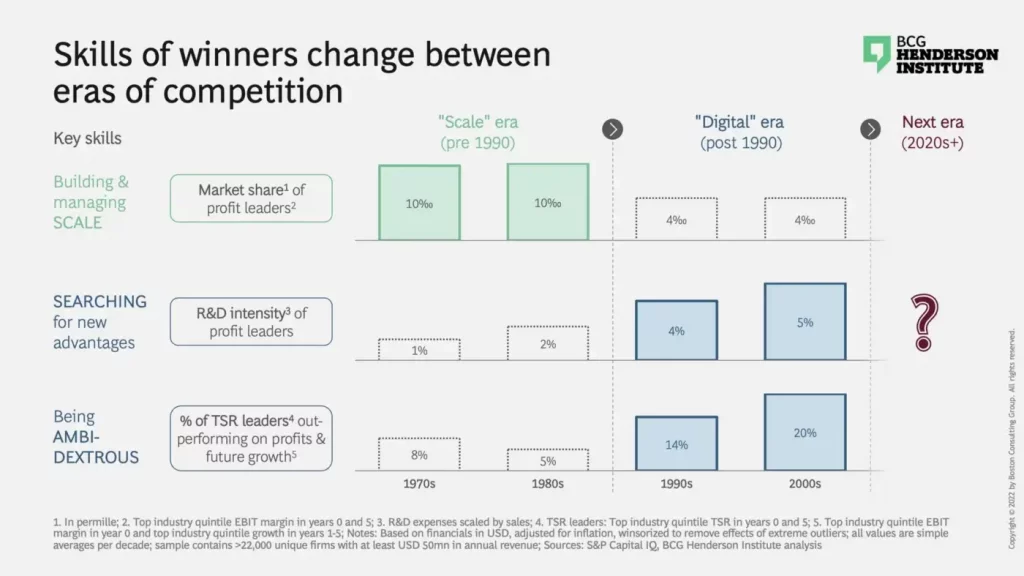

Evidence from a large, global set of firms confirms the fundamental shift in winners’ skillsets between the two eras of competition (see exhibit 2): The importance of scale diminished after entering the “digital era” — with a greatly weakened correlation between profitability and market share. Instead, the ability to search for new sources of competitive advantage to drive or pre-empt disruption became crucial. This is captured by a sizable increase in the R&D intensity of winners. Being able to simultaneously run and reinvent the business has always been key for sustaining outperformance. The ability to combine these apparently conflicting activities in “ambidextrous” organizations only gained importance as the threat of disruption increased and required timespans for reinvention contracted. Consequently, today’s most successful companies rely more than ever on their ability to balance the search for new advantages with the execution of their existing models.

But will mastery of these skills be sufficient for winning the next era of competition?

Raising the bar on ambidexterity

The next era will continue to be one of rapid change and high uncertainty, perpetuating the imperative of constant reinvention. This is driven by four key factors: First, technological innovation will continue to disrupt the ways we work, consume, and live — as AI frees up human minds from menial tasks and as the metaverse shifts many social and economic interactions to the digital realm. Second, in an increasingly polarized society, companies’ words and actions will have significant and hard-to-predict impacts on performance. Third, as geopolitical tensions and protectionist tendencies increase, the threat of supply chain disruptions rises. Finally, climate change will continue to drive volatility, both through crises related to extreme weather events, as well as by creating fundamental shifts in consumer demand, regulation, and — as a result — asset valuations.

At the same time, resource constraints will tighten significantly, along two dimensions: We are increasingly aware of our ecological limits, which continue to close in on us. Natural resources are becoming scarcer or harder to obtain (e.g., copper, cobalt, and freshwater) and our planet’s capacity to absorb pollution is close to critical limits.[1]E.g., the current Global Carbon Budget report indicates that, to reach the temperature goals set in the Paris Agreement, we would need to permanently cut anthropogenic CO2 emissions to 2020 levels, … Continue reading Moreover, we face the “end of free money”: Interest rates are rising and experts agree that there will likely be no rapid return to the near-zero levels of the past two decades. The U.S. Federal Reserve currently projects its funds’ rate to remain higher in the long run than at any point since the beginning of the new millennium, with the exception of the 2007–08 financial crisis.

In this new context, the need for constant reinvention to pre-empt disruption will endure. However, this will need to be achieved under much tighter resource constraints — so the search for new advantages must become more efficient and productive. At the same time, rising discount rates will induce a shift in investor preferences away from long-term growth towards short-term profitability — so the realization of existing advantages will also be more important than ever.

While ambidexterity will remain a crucial skill, it will be harder to achieve than ever — with additional pull on both ends of the search–execution–spectrum. We believe that winners of the next era of competition will be those that seek to break rather than balance this trade-off by becoming “co-ambidextrous” with their customers.

Introducing co-ambidexterity

Traditionally, ambidexterity has been seen as a balancing act, wherein firms allocate resources and management attention between execution–serving customer’s needs–and the search for better ways to serve these needs and, thus, renew their competitive advantage. These processes are often compartmentalized, being run by different parts of the organization and on different timescales–with new insights from the search being incorporated intermittently and haphazardly into execution.

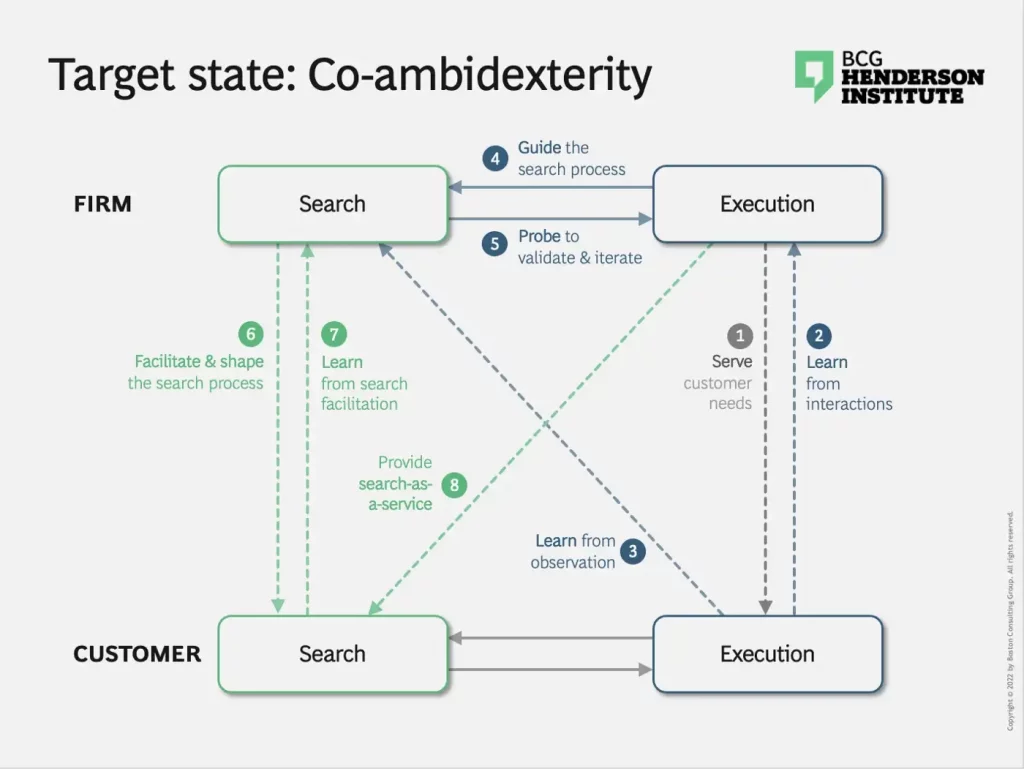

We believe that this approach can be fundamentally enhanced in two key ways: First, by fostering a deeper integration between search and execution; and, second, by recognizing and leveraging the customer’s own ambidexterity and directly interacting with their search process, not just their execution process (based on immediate needs). These actions will unlock new efficiencies and paths to generate value by satisfying existing needs in new ways and by identifying deeper or new needs. Exhibit 3 illustrates the key activities of a co-ambidextrous organization.

Deeper integration of execution and search

The first element of co-ambidexterity is creating a deeper integration of execution and search, by continuously leveraging the data resulting from natural or induced variance in execution. This will require a shift in mindset away from viewing execution and search as largely distinct processes, instead treating the execution of routine tasks as an opportunity to identify new ways of enhancing efficiency.

Practically speaking, this means leveraging learnings from interactions with the customer’s execution activities (number 2 in exhibit 3), during the sales process or by observing how a customer interacts with a product or service. For example, in the era of sales pitches conducted via Zoom, sales executives can leverage recordings to analyze the ways clients engage with message and messenger. As a result, every sales call also becomes an exploration — turning the sales process, the epitome of execution, into a treasure trove for the firm’s search for new advantages. Moreover, firms can leverage data from connected devices to learn how customers use a product, what alternative uses it may have, and infer what the customer wants next.

Firms can also actively embed search components into execution, by embracing experimentation — striving not for optimal execution of an established process, but rather constantly testing different permutations to artificially introduce variance. For example, companies like Booking.com or Microsoft conduct thousands of online experiments per year to identify potential improvements to user experience.

Finally, companies can learn by observing customer execution (number 3) even when it is not directly linked to their own sales processes or products, by leveraging information on customer behavior gained from third parties. For example, based on data provided by the Chinese online retailer TMall, which suggested that customers who bought Snickers chocolate bars also bought spicy snacks, Mars created a “Spicy Snickers Bar,” which became an instant hit.

The information gained in these ways can be used to guide the firm’s search (number 4) for new offerings and models.

Tightening the integration between search and execution also works in the opposite direction, by having the search process probe execution (number 5), i.e., testing new ideas in the marketplace early and regularly to validate them. For example, SmartWool, a New England-based apparel company, has used its Facebook page to recruit field testers who buy and test new products, providing the company with crucial insights about their performance, suggestions for improvements, and even ideas for new products.

A tighter integration of search and execution can yield tangible economic benefits. First, increased precision in search: Based on learnings from customer interactions (and observations via third parties), firms find out more about their customer’s immediate, explicit, as well as potential, implicit needs — information that can enhance search productivity. Second, by regularly colliding potential new solutions with the marketplace, firms can accelerate search cycle times to select, scale, and realize new offerings. Third, based on experience gained from conducting regular trial runs of new products or services, firms will also become better at rolling out product or process improvements.

Leveraging the customer search process

The second key component of co-ambidexterity relates to recognizing the customer’s own ambidexterity.

All too often, customers are viewed by firms as being only executors — satisfying their known, immediate needs. However, customers are also engaged in a search process of their own. This can be a functional problem-solving process, the search for a better solution to a known issue. Or the search can be a goal in itself, representing a journey of self-discovery and personal growth. For example, purchasing a bottle of wine may not only be the expression of a desire to taste the beverage (and enjoy its effects) but a learning journey in winemaking and culture. Similarly, buying a pair of running shoes is an expression of a deeper desire to stay active and fit.

Recognizing this, firms can engage with the customer’s search process: They can act as facilitators (number 6) — helping the customer to identify how to best satisfy a specific need. For example, NZXT, an American computer hardware manufacturer, offers a custom PC building service, which differentiates itself from the competition by allowing customers to specify, alongside their budget, which games they want to play on their PC and what graphical performance they expect, before recommending a set of components that fits these requirements. This enhances customer convenience, as they do not have to navigate confusing third-party performance benchmarks or reviews to select the appropriate hardware.

In facilitating the search process, companies will learn (number 7) more about individual customers’ desires, which can serve as a crucial input to their own search process. Google, for instance, is constantly leveraging its insights into what people search for not only to improve the service of search but also to monetize it through advertising revenue. Finally, firms can also shape (number 6) customers’ needs by intervening in the search process and guiding it in a certain direction. For example, fashion e-commerce websites like Zappos, through their “wear it with” or “complete the look” recommendations, nudge customers to purchase other items complementing a selected piece.

These activities also hold significant potential for value creation. First, based on improved knowledge of the customer’s individual needs, the firm can provide a superior value proposition, by tailoring or targeting their offerings. For example, LEGO has introduced the BrickLink Studio service, where customers can use a digital tool to create a virtual design of whatever they want—which LEGO then analyzes to sell them exactly the bricks needed to create that design at home. Second, firms can shape the customer’s search, which can be remarkably powerful. For example, it has been reported that about half of all products sold by Amazon are first presented to customers by a personalized recommendation engine. Going one step further, firms can anticipate and act on potential future needs, increasing revenue and, if done right, customer satisfaction. For example, both HP and Brother have programs that automatically ship replacement toner to customers whenever their printers send out a “low ink” signal.

Finally, firms can find new ways to monetize the customer interaction, executing the customer’s search by providing search-as-a-service (number 8). This service may be targeted at helping customers to find the best solutions for their explicit needs, which some companies have made the core of their business, e.g., metasearch engines that allow comparing offerings, such as US-based travel firm Kayak. Others, such as Nike, have found ways to enhance their core offering: The Nike Fit app allows customers to measure their foot size and shape, helping them to find the right shoe size, which may differ among sneaker models. This makes customers feel more secure in their purchasing decisions, while also allowing Nike to improve inventory management and reduce the number of costly returns. Alternatively, companies may monetize the customer’s journey of growth and self-discovery itself: For example, the Raj Parr Wine Club is a subscription service that offers biannual shipments of 6 bottles of wine for a fee of USD500 per shipment. While much more expensive than competing services, it includes sommelier Raj Parr’s phone number and encouragement to discuss the world of wines with him, which is appealing to (aspiring) wine connoisseurs.

Together, the key components of co-ambidexterity hold the potential to be crucial advantages in a new era of competition — enabling more efficient and productive search in a resource-constrained setting, as well as opening up new paths to value creation in an era where pressure on profits is increasing.

Plotting the path towards co-ambidexterity

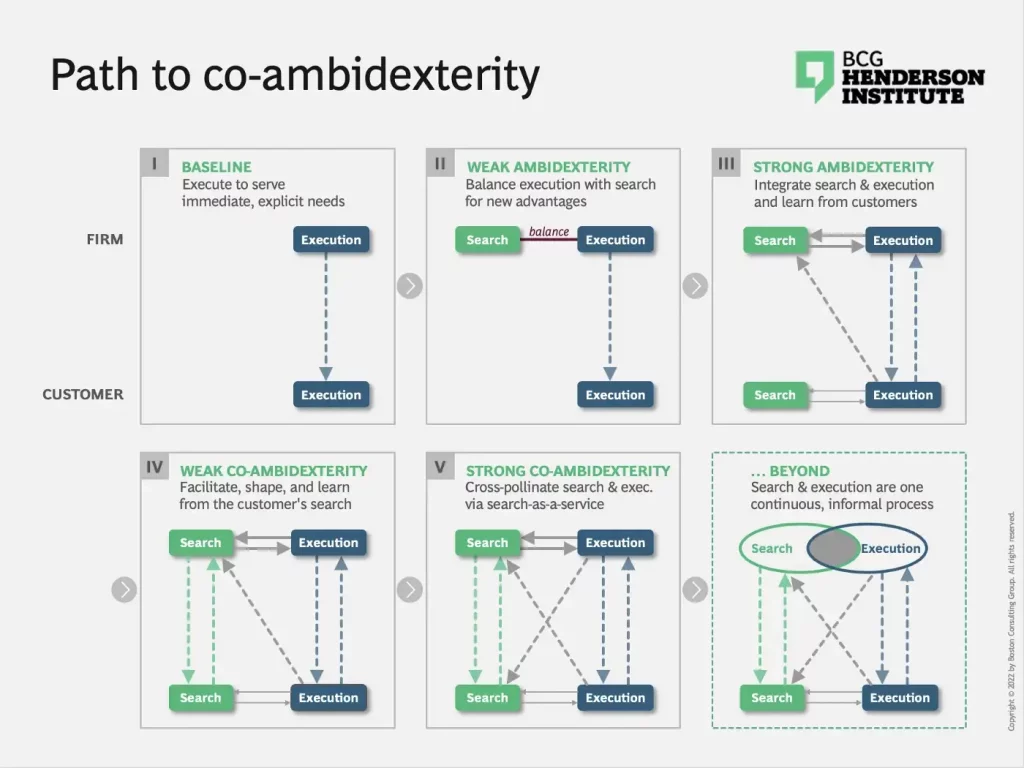

The path to co-ambidexterity may differ from company to company. In exhibit 4, we plot a plausible evolution for a company, starting from a traditional model focused on execution efficiency.

Initially, the firm is purely focused on execution, serving the customer’s immediate, explicit needs. In stage II, a parallel search process is being run, which the firm tries to balance with the demands of the day-to-day running of its business. Insights from the search are intermittently integrated into the core execution activities. We call this weak ambidexterity. In moving to stage III, the firm strives towards a tighter integration, embedding exploratory components into its execution activities, using this to guide its search, and regularly probing into execution to iterate and validate new solutions.

In stage IV, the customer’s search process is facilitated and potentially shaped by the firm, with learnings from these interactions guiding the firm’s search for new advantages. Based on its more complete view of the customer, the firm works to also satisfy their potential, implicit needs. This is a weak form of co-ambidexterity. Finally, the company reaches stage V by executing the customer’s search process by providing search-as-a-service, thereby cross-pollinating its search and execution activities with those of the customer and becoming strongly co-ambidextrous.

We can envision a stage beyond our current target picture of co-ambidexterity, at which the firm’s search and execution are fully integrated: Rather than being institutionalized as separate activities, they become one continuous, informal process, wherein each employee is both executing and searching.

This may entail small- and large-scale decisions being made by algorithms, based on a detailed and fully up-to-date understanding of customer desires and market context — akin to Netflix’s recommendation engine, which constantly updates its suggestions based on an evolving understanding of users. It also implies an increasing consolidation of roles. For example, at algorithm-based hedge funds, which constantly tune their trading strategies to adapt to changing market situations, traders and coders are one and the same, because the timeframe of operation does not allow for separation.

By moving to this stage, firms further enhance search accuracy and achieve cycle times at algorithmic speed.

Putting in place the pre-requisites for co-ambidexterity

So, which concrete pre-requisites can companies put into place now in order to start their journey towards co-ambidexterity?

Shift the mindset away from execution vs. search

First, a mindset shift is required: From merely striving to balance search and execution activities, to integrating them in order to harness synergies. This means dissolving temporal, spatial, and bureaucratical boundaries between these activities — by making search continuous, rather than discrete (i.e., constantly feeding information from execution to R&D, and constantly testing potential solutions) and by making search a part of every role, every team, and every meeting.

Rethink customer interactions

Second, firms need to rethink customer interactions: Rather than focusing on optimally serving the average customer’s needs, companies need to embrace the variance across customer interactions as a source of information on clients’ individual, implicit, and potential needs. Moreover, companies need to actively engage with clients (and non-clients) search processes outside of sales discussions. This may take the form of classical market research. However, firms can also embrace more ambitious approaches: For example, in 2010, to kickstart new thinking, Hindustan Unilever, the Indian consumer goods giant, sent all of its fifteen thousand employees — from the CEO to the receptionist — to meet customers for unscripted conversations, and to record their observations regarding new ideas. This resulted in a significant uptick in innovation and portfolio freshness.

Bolstering imagination capabilities

To extract maximum value from the wealth of information obtained by reconceiving the customer interaction, the search process must become part of every employee’s job. To enable this, firms need to foster non-traditional skills in their employee base, e.g., contingent thinking, analogical reasoning, and richness of mental models. In our book The Imagination Machine, we detail the key capabilities required for developing novel ideas, as well as the environment conducive to systematically harnessing imagination.

Leveraging technology

Once human imagination has been fully activated, companies can deploy digital tools to enhance it: For example, to spark new ideas, firms can leverage AI to detect interesting patterns that may be beyond the perception of humans. When it comes to designing new offerings, the metaverse holds significant potential to enhance efficiency: Costs and challenges of generating options can be decreased significantly by representing, developing, testing, and communicating ideas digitally, bypassing the obstacles of inertia and cost in the physical world.

Building or using digital platforms is another key to success: It is no coincidence that the companies closest to achieving co-ambidexterity operate large, highly customizable, marketplace platforms — e.g., Alibaba and Amazon — which allow them to interact directly with customer execution and search.

Evolve the business model

To capitalize on their broadened customer interactions and enhanced capabilities, firms need to upgrade their business models in substantive and non-incremental ways.

This may entail creating processes to shape and proactively execute on customers’ potential future needs. For example, McGraw-Hill has created a powerful learning ecosystem, wherein students use electronic textbooks to study and complete assignments — with progress being transmitted not just to their teachers, but also to the company itself. Leveraging this connection, McGraw-Hill can, for example, point someone struggling with an exercise to a book or video course that may provide assistance. Going one step further, McGraw-Hill could infer career interests from observing the kinds of topics users are interested in learning about, and could use this information to, for example, set up an interview preparation service it could direct them to.

Companies may also foster capabilities for mass personalization, in order to translate their more in-depth knowledge of customers’ desires into tailored offerings that improve the customer value proposition. This personalization should extend beyond inserting a customer’s name into a marketing email or having their data ready when they call customer service: The goal should be to tailor the entire experience, physically and virtually, to the customer. For example, San Francisco-based start-up Unspun manufactures jeans to order, based on a 3D body scan of the customer, conducted either in-store or remotely with an iPhone. The jeans are 3D-printed, requiring a much closer integration of sales and manufacturing processes than that of conventional apparel brands. Key benefits are enhanced customer satisfaction and significant cost-savings due to the lower need for inventory space and fewer returns.

Finally, companies can strive to extract value from the customer’s search process. While not every company can create a (meta-)search engine, comparison platform, or wine subscription service, we believe that many will be able to generate additional value by viewing their offerings as something that could satisfy not only immediate needs but enable a journey of self-discovery or growth. Nike has been particularly successful in this regard with its “Run Club” and “Training Club” platforms, which go beyond selling sports apparel — the Nike customer’s immediate need — by offering social events, challenges, and personal training provided by third parties. This has not only allowed Nike to tighten its bonds with customers, but also acted as a springboard into fitness-adjacent categories, such as mental health and nutrition, thereby opening up new revenue streams.

Defining new measures of success

Finally, to achieve and sustain co-ambidexterity, businesses will need to define new measures — that go beyond the traditional focus of exploitative proficiency, such as market share and profitability. Instead, firms need to measure their ability to holistically approach the customer interaction and synergize search and execution activities: For example, by tracking the rate and success of experimentation (relative to competitors), the rate of learning, and the value created from providing personalized offerings or proactively executing on customer needs.

The next era of competition is at hand. To succeed in an environment of rapid change, high uncertainty, and tighter resource constraints, firms must raise the bar on ambidexterity — breaking the inherent trade-off to achieve both more stringent execution and a more productive search for new advantages. This requires deeper integration of the firm’s search and execution activities, as well as interacting holistically with the customer across both types of activities. In other words: becoming co-ambidextrous.