In a world of accelerating change, firms trying to sustain a competitive edge need to constantly reinvent themselves. This has become increasingly challenging as businesses confront uncertainty and complexity across multiple dimensions, compounded by encroaching resource constraints. Indeed, our research shows that change efforts fail more often than they succeed: A startling three out of four such programs fall short of their targets.

We argue that change leaders can improve their odds by learning from moviemaking—an industry whose product has inspired people for more than a century but that has remained largely untapped as a source of insights for driving change.

The movie industry can be considered the epitome of successful project management. Movie productions, much like complex corporate projects, are temporary systems that require meticulous coordination among specialized teams, sound decision-making, and ways to stimulate and manage creativity. Over decades, the industry has amassed considerable experience, following a process that has been repeated and honed, and which is still evolving today.

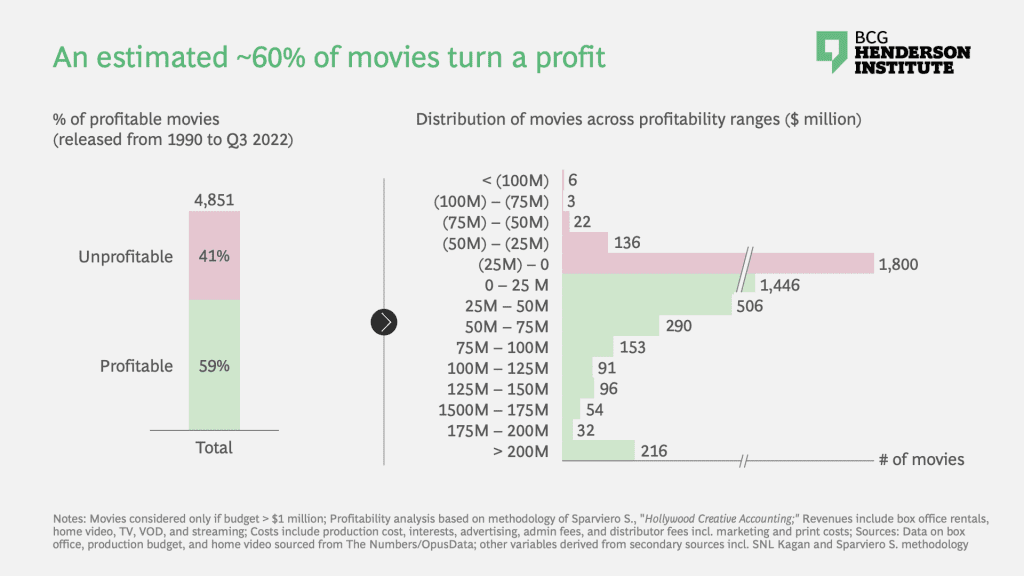

Some have labelled the film industry as a volatile, hit-driven business in which executives have to place substantial bets with the hopes of landing a blockbuster success.[1]Elberse, Anita, “Blockbusters: Hit-Making, Risk-Taking, and the Big Business of Entertainment” (2013) But by the standards of corporate change, moviemaking is disproportionately and consistently successful—despite having to contend with the subjectivity and unpredictability of human taste. According to our research, roughly 60% of movies turn a profit (see exhibit 1).

In this article, we detail practices employed in the film industry and discuss how they can be applied to corporate change projects to boost your odds of success. We tackle four important strategic questions:

- How can one optimize decision-making for selecting and executing projects?

- What steps can one take to foster alignment and coordination for effective execution?

- How can one ensure that discipline does not stifle creativity?

- How can one continuously evolve and learn from past successes, without becoming trapped by them?

1. Adopting a Choiceful Approach

Contrary to popular perception, moviemaking is not solely guided by artistic intuition. Rather, it is as much science as it is art, particularly when it comes to the processes of selecting and executing projects.

Assess the Drivers of Success, Scientifically

The film industry faces considerable uncertainty: Because movies are experiential products, their quality cannot be fully assessed until they are experienced by the consumer, and their success largely depends on the subjective interpretations and ever-changing taste of moviegoers.

To mitigate uncertainty in this high-stakes industry (the average movie budget is roughly $40 million)[2]According to a database of nearly 5,000 movies released between 1990 and 2022 (The Numbers, Opus Data); the database only includes movies whose budget is above $1 million , filmmakers have adopted a rigorous and systematic approach to discern success factors (see “A Playbook for Movie Success?”). This has helped shape not only project selection, but also marketing and distribution strategies and—in recent times—even parts of the production process itself.

This approach entails extensive data collection, which was traditionally conducted primarily through audience research (polls, focus groups, and test screenings). An average film has three test screenings, though some go through as many as 10 or more.[3]Goetz, Kevin quoted in “The iconic Hollywood films transformed by test audiences,” BBC (2022) Movies like Jaws (1975) and Titanic (1997) were altered before release due to feedback from a test screening. A particularly famous example of such an alteration is the addition of a scene at the end of The Shawshank Redemption (1994): the unforgettable reunion between Red (Morgan Freeman) and Andy (Tim Robbins) in Zihuantanejo.

In recent years, these approaches have been complemented by access to new data sources (such as social media feeds, online reviews, and streaming platforms) and modern data science techniques, which have enabled filmmakers to secure insights of unprecedented depth and granularity. For example, firms like ScriptBook and Epagogix have developed natural language processing algorithms to predict whether a film will be commercially successful solely based on its script and use these insights to recommend changes to filmmakers during the writing stage.[4]Retrieved from https://www.scriptbook.io/#!/ Analytics have also begun to play a role in optimizing the production process. For example, Netflix has developed an algorithm to compare the cost of different shooting locations.[5]“Data Science and the Art of Producing Entertainment at Netflix,” Netflix Technology Blog (2018) Finally, 20th Century Fox has partnered with Google Cloud to create Merlin video, a deep learning computer vision tool that can analyze trailers and predict a movie’s audience, which helps the studio decide how to best market its movies.[6]How 20th Century Fox uses ML to predict a movie audience,” Google Cloud Blog (2018)

Contrary to moviemakers’ scientific approach, change leaders in other industries often rely on intuition or generalizations from past experiences. Our research also suggests that executives lean on flawed heuristics—for example, adhering to “known best practices” or outside “expertise” without systematically looking at the data, which often results in untailored decisions.

➤ Instead, corporate executives need to embrace an evidence-based approach to change. This entails thoroughly preparing the journey by assessing the organization’s readiness and developing a detailed understanding of the drivers of success, drawing insights from the full range of historical evidence, including beyond their own firm. For successful execution, corporate leaders should build analytical capabilities that will help generate insights and improve decision-making throughout all stages of the change process. For example, corporations can implement real-time tracking or workplace analytics tools, such as pulse check surveys and performance dashboards, and a database of analogous projects.

A Playbook for Movie Success?

Forecasting and understanding success has been a longstanding goal in the film industry. In 1983, screenwriter William Goldman concluded: “Nobody knows anything […]. Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess.”

There is no shortage of examples to illustrate that success (or failure) might just be a matter of (bad) luck or timing. For example, Iron Eagle and Top Gun were released around the same time (1986) and had similar budgets ($18 million and $25 million, respectively) as well as storylines, but Iron Eagle only grossed $25 million at the US box office, whereas Top Gun made $180 million.

Over time, however, academics and practitioners have decoded a set of factors displaying significant statistical relationships to box office success. A movie’s production budget is considered the most important factor, but this may be an instance of reverse causality, as movie studios usually use expected revenues to set the budget. The budget is also a proxy for other considerations, like the number of cinema screens on which the film will be played or the studio’s bargaining power. Historical box office performance of actors and directors matters a lot, along with their popularity and artistic recognition. Some genres, such as action and adventure, typically do better than others. Certain storyline patterns, like a happy ending, are also more likely to succeed. Sequels or adaptations usually do well because they already have a fan base. The opinion of critics and online reviews matter too, both in predicting and influencing success.

However, this “formula” is no panacea, and the industry is far from being able to fully explain, let alone predict, success. As an illustration, many movies that checked all the boxes still failed: The Adventures of Pluto Nash (2002), John Carter (2012), and The Last Duel (2021) all had popular stars and a budget of $100 million or more, but were commercial failures.

Similarly, a model developed by The Economist could not account for 20% of the variation in revenues across movies, suggesting that other unidentified factors must play key roles.[7]“Silver-screen playbook: How to make a hit film,” The Economist (2016) In particular, as Abhijay Prakash, President of Blumhouse Productions, pointed out to us, “The production process itself matters. One of the largest failings of this data science and modelling is that they [often] do not account for execution.”

Establish a Systematic Approach to Project Selection

Movie studios and production companies may review hundreds of ideas and scripts, out of which only a handful will ever receive the go-ahead for production.[8]Epstein, Edward J., The Big Picture and the New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood (2005) Underlying this is a structured approach to project selection based on criteria honed over decades: the green-lighting process.

Every movie project begins with an idea, often generated by a writer or creative team. If this idea shows potential, it receives funding for a development phase, where it is fleshed out into a complete script, and an initial budget is developed to set the financial boundaries of the project. The project then undergoes an exhaustive assessment that considers a set of selection factors, including predicted return on investment and strategic alignment with the studio’s pipeline. Based on this assessment, movie executives and financiers decide whether to green-light the movie.

In stark contrast to this systematic process, the initiation of corporate transformations is often overly simplistic: projects may be accepted as recommended and a monolithic change management approach is applied.

➤ Instead, leaders need to fit, vet, then optimize and de-average organizational transformations, adopting strategies that correspond to the specific nature of the change required. This approach involves delving into the problem’s complexities, systematically assessing the options available, and ensuring that a plausible business case supports the project.

2. Fostering Alignment and Coordination

It is tempting to idolize masterpieces that emerged from a chaotic production—for example, Apocalypse Now (1979), which faced numerous challenges during production and resulted in cost overruns of roughly twice the original budget. Or Jaws (1975), nicknamed “Flaws” by the crew after the number of shooting days nearly tripled. Nevertheless, the reality of most moviemaking is strikingly different. Michael Beugg, an executive producer known for Little Miss Sunshine (2006) and La La Land (2016), told us: “There was a theory that the most chaotic films led to the greatest creative successes, but I don’t hear this wisdom repeated anymore.” Rather, modern moviemaking exemplifies managerial rigor and disciplined execution: As Beugg says, “creative success is not a single magical moment, but the culmination of a process.”

Empower Hands-on and Dedicated Leadership

The movie industry owes some of its executional discipline to the hands-on and dedicated nature of its project leadership, particularly the film director and producer, who are responsible for the creative and strategic or operational dimensions of a movie, respectively. Directors and producers are highly dedicated to their projects: Once a movie is green-lit, it becomes their sole preoccupation. Directors, in particular, are immersed in every detail of the story—every scene, costume, and set design.

Moviemaking is also special in that managerial layers can easily be bypassed, and communications channels do not always mirror hierarchical structure: Directors are hands-on and interact directly with teams across all layers, from actors to technicians, and sometimes even operate the camera themselves. This level of involvement enables direct and short feedback loops and supports effective communication. While not all moviemakers exert the same level of control, leadership is usually involved throughout the entire project, overseeing all aspects of a movie’s production, from conceptualization to the final release.

Relative to moviemakers, change leaders in other industries often assume a weaker role—becoming distracted by the ongoing demands of their daily business or line function and having to rely on the project’s administrative machinery to move things forward. A common pitfall is the artificial separation of strategy and execution, a byproduct of hierarchical structure.

➤ Instead, change leaders should foster alignment by engaging in both strategy formulation and execution and by being more hands-on (or nominating executives who can be). They can set the project’s tempo by acting as a drumbeat function, creating regular communication channels and checkpoints to monitor progress, removing obstacles, and rapidly adapting as circumstances change.

Institute Sacrosanct Guiding Documents

The need for seamless coordination becomes paramount during the production phase of the moviemaking process, which must align multidisciplinary teams while adhering to a strict budget and timeline. About 50 to 60% of the costs of a film are typically incurred at this stage, so any delays can quickly lead to significant cost overruns. To facilitate discipline, moviemakers rely on what Blumhouse Productions’ Prakash described to us as a set of “sacrosanct documents.”

At the heart of the administrative and creative machinery is the script, the bedrock from which all other documents derive. The production schedule also plays a crucial role, offering a highly detailed roadmap that outlines daily milestones and activities of the production process. The budget encapsulates all financial aspects of the production, while the shot list details each scene that needs to be captured, working in tandem with the storyboard, a set of sketches providing a visual representation of the film sequence. Lastly, daily call sheets help organize shooting days by specifying required cast, crew, and equipment. Together, these documents form the backbone of any production, providing a framework for aligning and coordinating teams: As Prakash says, they ensure that “everybody knows the rules and […] exactly what they are supposed to be doing.”

But filmmakers also rely on supporting mechanisms: “There is a lot of process put into adhering to these documents,” Prakash told us. Progress is tracked regularly with reports such as the daily production report, which tracks the accomplished work, including scenes shot, film footage recorded, and crew work hours. Additionally, daily hot costs provide real-time tracking of the day’s expenses. Specific teams oversee these activities: For example, the producer’s unit and its accountants report on spending activities, while the script supervisor ensures that everything is shot as scripted.

Corporate change efforts also employ a variety of alignment tools such as Gantt charts, roadmaps, and governance matrices. But their usefulness is often limited, as these tools lack standardization and are unfamiliar to most employees—transformations are, after all, relatively rare events in a professional lifetime.

➤ Enhancing effectiveness demands a refined focus on a few select tools, frequent iteration, and effective information sharing. Finally, change leaders must educate all relevant stakeholders on these tools, instead of assuming prior familiarity.

3. Bridging the Gap between Discipline and Creativity

While the execution of a movie project emphasizes discipline and control, it is crucial to recognize that moviemaking is also an artistic endeavor, which requires creativity. Here is how moviemakers tackle this trade-off.

Set Boundaries to Safeguard Creativity

One approach is to set well-defined boundaries within which creativity can thrive without jeopardizing the discipline of the execution. As Prakash told us, “Creative freedom is usually undergirded by some simple rules.” These rules are established during the movie creation process, which gradually transitions from a flexible to a more fixed context: In the early stages, iterations are encouraged, for example on the budget or the script. Once these are finalized, they form the boundaries for the subsequent stages of production. For example, directors have flexibility in how they interpret a script, providing they adhere to the budget and timeline. Actors may be encouraged to experiment with how they interpret a scene—but this creative freedom operates within the previously defined boundaries.

A crucial component of balancing the trade-off also lies in the explicit distribution of responsibilities among leadership roles, especially between the director and the producers: Their collaboration ensures a balance between artistic integrity and commercial viability.

Corporate change projects also need to balance control and ingenuity—but are instead often managed with a mechanical mindset, over-emphasizing control while downplaying soft factors.

➤ The movie business shows that it is possible to safeguard creativity by establishing clear decision rules and processes as well as other constraints (for example, budget and timeline), thereby ensuring that employees know the extent of their autonomy—and feel empowered to experiment within these boundaries. Finally, decision-making power must be balanced between creative and operational roles.

Motivate through Ownership and Purpose

Moviemakers’ approaches to motivation also play a crucial role in ensuring the process remains focused while fostering creativity. Admittedly, the film industry benefits from certain systemic characteristics that enhance motivation: These include the public nature of the work, the opportunity to inspire audiences, and the possibility of external recognition, for example at film festivals or award shows. However, filmmakers do not only rely on these extrinsic elements, but also nurture a culture of ownership and purpose.

For one, every individual involved in the moviemaking process gets credit, regardless of their position in the hierarchy—giving every team member a sense of personal accountability. Additionally, the division of responsibilities into specialized jobs allows employees to exercise their competences and be recognized for it, which fuels their intrinsic motivation. Importantly, while tasks are subdivided, it remains clear how they contribute to the final product. Finally, the moviemaking process is highly collaborative, which means that leaders—such as the director—can inspire their teams by displaying their passion and proficiency.

In contrast, corporate approaches to motivation usually rely on top-down prescription, presenting change as an event imposed on employees rather than as an opportunity for their active participation. But traditional management tools, such as goals, quotas, or monetary incentives have become insufficient to motivate today’s workforce.

➤ Instead, corporate leaders should energize the organization and foster alignment by appealing to “head and heart.” A well-articulated, activated, and embedded purpose can serve as a powerful motivator—not dictating only what to change but explaining why. Additionally, leaders should allow employees to work on, or at least see, the whole problem, by encouraging ownership from end to end.

By incorporating the above tactics, companies can increase the chances of successfully navigating their next change project. Our script could have ended here, but we feel the story would not have been entirely complete.

4. Institutionalizing Renewal—Lessons from Recurring Success

Given the pace of change in our world, corporate transformations are becoming more frequent. And while pulling off a successful transformation once is hard enough, doing so repeatedly is another matter entirely: Organizations that have successfully concluded one change project may become overly reliant on their past recipes for success. This will lead to trouble as circumstances change, rendering previous success factors obsolete. Conversely, some organizations might fail to understand why a certain approach worked and codify the practices that once led to success.

Thus, we must address one further essential question: How can one continuously evolve and learn from past successes, without becoming trapped by them?

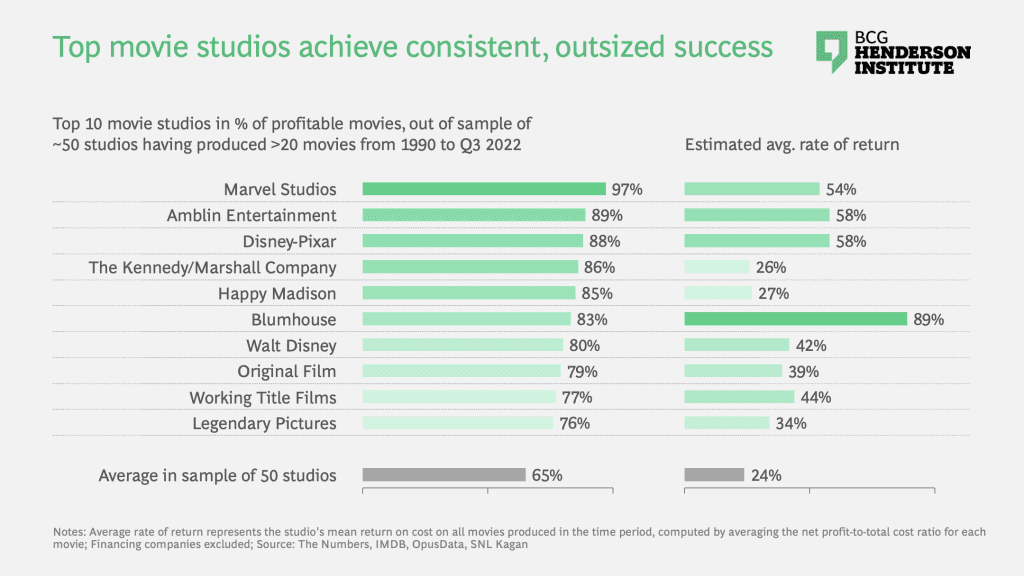

This is also a conundrum in the film industry, but some organizations have demonstrated a remarkable capacity for learning and renewal by staying relevant and competitive over time. From 1990 to Q3 2022, a set of studios and production companies have achieved both recurring and exceptional results, consistently making profitable movies (see exhibit 2).

These companies have found a way to institutionalize learning, employing a set of practices that support continuous change, innovation, and adaptation.

Cultivate a Culture of Constant Learning.

These studios have managed to create an environment conducive to learning by facilitating the collision of ideas among teams. Pixar exemplifies this approach, “being as close to a learning organization as there is,” argues management writer Peter Sims.[9]Sims, Peter, “What Google Could Learn From Pixar,” Harvard Business Review (2010) The animation studio encourages iterative, honest feedback to facilitate learning, underscored by robust peer-review processes. During production, Pixar uses its famous dailies—sessions wherein incomplete work is presented for feedback. Another pivotal aspect of their open feedback culture is the brain trust: When directors and producers face difficulties, they can convene a small group of trusted Pixar colleagues to discuss work in progress and receive non-binding feedback. Moreover, the exchange of ideas is encouraged regardless of hierarchy, fostering a culture where everyone feels safe to share new thoughts. Ed Catmull, co-founder of Pixar, states in his book Creativity, Inc. (Random House, 2014) that he worked to ensure that “anyone could be able to talk to anyone else, at any level, at any time, without fear of reprimand.”

Furthermore, Pixar and other successful studios have put an emphasis on self-assessment and on embracing errors as learning opportunities. This helps to reveal underlying difficulties at the organizational level, which may be concealed by success. “We must constantly challenge all of our assumptions and search for the flaws that could destroy our culture,” Catmull explains. Pixar has operationalized this idea by instituting postmortems: Upon project completion, teams dissect challenges faced and discuss lessons learned. Importantly, these lessons are codified.

➤ Firms striving for a culture of learning should consider adopting similar practices. For example, leaders can institutionalize lessons learned from crises by following a three-step approach: evaluating performance, extracting insights through a post action-review, and identifying capabilities that need to be improved or introduced to be better-prepared for the next challenge. More generally, corporations need to learn how to learn. To that end, they should make learning a priority for the C-suite—which entails embedding learning into everyday workflows and putting learning at heart of the company mission.

Incorporate Fresh Perspectives in the Organization.

The most successful studios also achieve renewal by systematically looking for expertise and ideas that are complementary to what their organization already has. This allows them to source new insights and see challenges and opportunities from a different angle. “Do not discount ideas from unexpected sources. Inspiration can, and does, come from anywhere,” Catmull writes.

One way they achieve this is by closely collaborating with the broader ecosystem—both other organizations involved in the moviemaking process and the moviegoers themselves. Disney, for example, has created a startup incubator called “Disney Accelerator.” According to Disney’s former chief strategy officer Kevin Mayer, “the accelerator program is less about earning a quick profit and more about […] injecting Disney’s upper management with energy and ideas.”[10]Nakashima, Ryan “Disney taps startup for BB-8 droid toy,” The Seattle Times (2015) For example, an incubated company called Sphero co-created numerous robotic toys with Disney, including the BB-8 droid toy featured in the most recent Star Wars trilogy.

Another way to bring in fresh perspectives is through staffing decisions. For example, out of the 15 directors that led movies in the Marvel Cinematic Universe until 2019, only one had prior experience in the superhero genre.[11]Harrison, S., Carlsen A., Škerlavaj, M., “Marvel’s Blockbuster Machine: How the studio balances continuity and renewal,” Harvard Business Review (2019) This management decision resulted in the varied tones of the movies. At Pixar, to ensure the success of this approach, Catmull emphasizes the importance of ensuring that external hires have the confidence to speak up and question pre-existing mental models.

Incorporating fresh perspectives is also a challenge in the context of change efforts. As corporations grow, they inadvertently become inwardly focused. We recommend that organizations engaging in change efforts pursue opportunities for novelty, for example by mobilizing their ecosystem, or by co-creating with collaborators.

➤ Furthermore, recruiting new external leaders can help bring a distinct or complementary perspective to a company’s current situation. In fact, our research has shown that a change in the broader leadership team often improves the odds of transformation success.

Keeping up the movie industry’s success rate will require continuous learning as the world keeps changing: For studios, this means further reducing the residual unpredictability of movie projects as production costs keep climbing; it means keeping up with changing habits of consumers, particularly as competition for time and attention with other forms of entertainment increases; and it means taking advantage of new technologies and distribution models.

Corporate change should embrace these valuable insights from the world of moviemaking—not only to improve their odds of navigating one change project successfully, but to be able to do so, time and again.