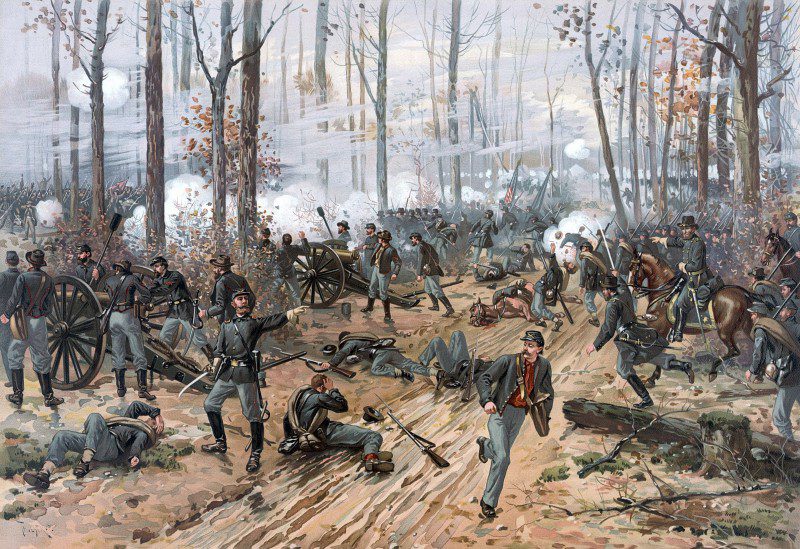

Featured image source: Thure de Thulstrup — Battle of Shiloh (Restoration by Adam Cuerden)

When politicians talk about waging war on something, my heart sinks.

They usually do it because they want to turn a crisis into a drama in which they can appear on centre stage and act out the role of tough, heroic leaders. Good judgement gets left behind in the dressing room. So as the rhetoric of waging war on COVID-19 spread around the world, I felt some foreboding.

That said, political and business leaders can in fact learn a great deal from the great commanders of history, if they know what to look for and where to look.

What to look for is how the great commanders handle crisis, the usual state of affairs in war. They do not turn a crisis into a drama — rather the opposite.

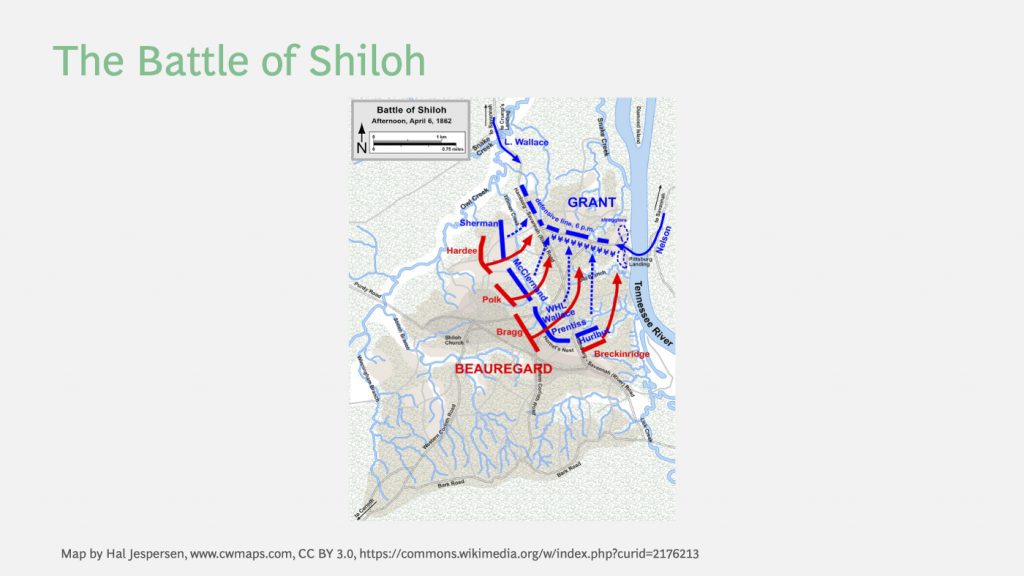

As for where to look, a good place to start is on the western bank of the Tennessee river on the morning on 6th April 1862, almost exactly one year in to the conflict which was to become the bloodiest war in American history.

Survive, Reset, Thrive

At about 8:30 am on that morning a small man wearing a battered slouch hat and a rough soldier’s coat disembarked from a steamboat at a place called Pittsburg Landing, mounted his horse and began galloping through the dense woodland to find out what was happening to the troops he had assembled there. Their positions extended out westwards towards an unprepossessing log meeting-house which served as a church and was known as Shiloh. It was now the headquarters of the division on the far right of his line, commanded by William Tecumseh Sherman.

The small man’s name was Ulysses Simpson Grant, the commander of the Union Army of Tennessee. What he found was mayhem.

He must have felt pretty bad, for it was partly his fault. Having beaten Confederate forces at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in February, Grant had been pushing south along the Tennessee river in order to take the railroad at Corinth, Mississippi, a vital link for the South. He expected the Confederates there to wait for him to attack them so that they could benefit from their strong defensive positions. At Pittsburg Landing, his raw troops, many only recently recruited, spent their time practising much-needed musket drills rather than digging defensive entrenchments. Now unexpectedly under attack, they and their open camps were being quickly overrun.

Grant visited each of his five divisions in turn. Many of his greenhorn troops were panicking. Just two hours after the main Confederate assault, ammunition was already running short. Actually, there was plenty available, some of it just lying about. Grant gave orders for ammunition to be distributed and told others to do the same. No-one else had thought to do so. ‘The men only wanted someone to give a command’, he wrote later.

Regiments were breaking. Some of their Colonels were galloping off in retreat ahead of their men. Where this was happening, Grant stepped in and rallied them. In the centre, he encouraged the divisional commanders who were holding on in what became known as ‘the Hornet’s Nest’, bringing them reinforcements. As units to the left and right withdrew to shorten Grant’s line, the position’s exposed flanks made it the epicentre of Confederate attacks. He told his commanders that they must ‘maintain that position at all hazards’. They held on till 5:30 pm, when they were finally forced to surrender.

But by then, Grant had established a continuous defensive line about a mile back and massed artillery on his left flank by Pittsburg Landing, where he expected the most threatening attack to come. So it did, at around 6:00 pm, and the artillery concentration of 50 guns beat it back. The fury of the Confederate assault abated and as dusk fell it petered out, just as heavy rain began to fall.

He had summoned reinforcements hours earlier. At 8:00 am, before getting off his boat, he sent word to his 3rd Division to join him from the north as soon as possible. Once on the field he worried about a bridge over Snake Creek over which he expected them to arrive and another further west over Owl Creek, at the end of Sherman’s line, both out of sight to his flank and rear. The 3rd Division was stationed only 5 miles away, but as dusk fell there was still no sign of them.

At about 9:00 am, with chaos and panic around him, Grant had penned a note in the saddle to General Don Carlos Buell, commander of the nearby Army of Ohio, which had been due to join him in his planned push south down the Tennessee river.

He urged Buell to come with all speed to Pittsburg Landing, leaving all his baggage on the east bank. The note was short, perfectly phrased, and without any ambiguity. He told Buell where he would be and that a staff officer would guide him to his place on the field. Buell himself arrived at 1:00 pm, but then Grant himself was occupied, personally rallying three regiments in succession as the crisis in the centre developed.

The first of Buell’s units crossed the Tennessee at about 5:00 pm and helped to repulse the final Confederate attack. At midday, the commander of Grant’s 3rd Division had started to march his men towards Owl Creek in the west, then learned that the Union line had moved further east, and so counter-marched back to the bridge over Snake Creek . They arrived after dark.

The night was quiet.

That evening, Sherman found Grant standing beneath a dripping tree, his coat collar around his ears and a cigar clenched between his teeth.

Sherman had sought him out with the intention of advising a retreat. As he spied his face, ‘some wise and sudden instinct’, he later recalled, prompted him otherwise. ‘Well Grant’, he said, ‘we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?’ ‘Yes’, said Grant. ‘Yes. Lick ’em tomorrow though.’

So they did. Whilst creating order out of chaos to make sure his army survived, Grant had been simultaneously re-setting, and the following day, they thrived, launching a counter-attack which took the Confederate commanders by surprise and drove their forces from the field in confusion.

From Good to Great: the difference

This late evening encounter, if it occurred as Sherman related, is arresting.

Both men had had very similar experiences during the previous 12 hours. Both sets of experiences had been traumatic, for Grant perhaps more so, because he bore a greater responsibility for what had occurred.

Yet Sherman and Grant were in very different places. The one saw defeat, the other sensed victory. Sherman was a very fine general, but Grant was a great one.

The difference is that Grant was a master of the executive’s trinity: leadership, management and command. In a business context I call command ‘directing’. The trinity can be thought of as three overlapping circles:

Each is a quite distinct discipline, drawing on very different qualities.

Leadership is about motivating people to achieve objectives. Management is about providing people with the resources they need to achieve them. Directing is about deciding what those objectives should be in the first place. It is an intellectual discipline, at the heart of which is strategy — the art of achieving a determinate goal with limited resources, against opposition, in an environment of high uncertainty.

Each aspect of the trinity demands different skills, but an organisation needs all three. Most of us have a natural inclination towards one or the other, so for most of us the answer is to strive for minimal competence in them all, and put together a leadership team which can cover all the bases. Those who are outstanding at all three are rare, and therefore celebrated. Grant was one them.

Confronted with a crisis, Grant placed himself in the centre of the trinity where the circles overlap, and shifted between all three so fast that he did them more or less simultaneously. War is in fact just a series of interlocking crises, even in a planned battle. Shiloh, which was not just unplanned but a daunting surprise, is a dramatic microcosm.

It is as if Grant’s mind was a clock with three hands:

The second hand is the leadership hand which whirrs round: he rallies his men, supporting and encouraging his strong divisional commanders and stepping in personally when the weak ones fail. He had the emotional discipline not to show his feelings. He hated the sight of blood so much he never ate red meat. That day he saw plenty of blood, mostly human.

The minute hand is the management hand which ensures people get critical resources, the most urgent of which at the beginning of the day was ammunition. He knew they couldn’t do everything at once so he sorted priorities and delegated execution.

The hour hand is the directing hand, which was thinking at a higher level all the time, discerning patterns and putting together a picture of the whole situation which included the state of the enemy. This was the one that was thinking about what was out of sight — such as the bridges — and wrote the note to Buell; that, as he rallied his regiments, was also thinking about where to move them; that decided to concentrate his artillery by the river; and that positioned his reinforcements to hit back the next day. For most of his generals it was a case of what Daniel Kahneman calls WYSIATI — ‘what you see is all there is’. Not for Grant. He overcame that and all the other usual biases.

Sherman’s mind-clock just had the second hand and the minute hand. At Shiloh, that was fine, because Sherman was a divisional commander and he only needed to lead and manage. Grant was the Army commander, and he needed to direct as well. Directing only needs to be carried out by a few, but they make a huge difference.

Grant’s qualities

Born in Ohio as the son of a foreman in a tannery, Grant was a West Point graduate, trained as a soldier. His business ventures were failures. The Civil War made him, and he went on to become the 18th President of the United States. He learned to master the trinity through experience, but a few traits of character helped him.

He was modest in manner, dress and habits. Famously unconcerned with his appearance, he ate even more simply than his staff, spoke simply and little, and hated pomp and ceremony. His ego was never going to get in the way of his dedication to his cause — the union. Not all of the great commanders were modest. But though some sought personal glory, none allowed personal interests to get in the way of achieving results. Dedication to a cause is something they all have in common.

That dedication may have strengthened another characteristic: courage. His physical courage was clear. He did not seek danger, and at Shiloh he only exposed himself to it when he had to, but when he did, he remained conspicuously unconcerned. Of possibly greater significance was his moral courage and resilience — an indifference not to danger but to setbacks. He made unpopular decisions when he felt them to be necessary.

Intellectually, Grant was comfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity, but he abhorred confusion. He constantly sought to understand reality, his mind dedicated to sense-making. Consequently, he was completely open to new information and to the ideas of others. But Grant also possessed the self-confidence to always form his own final judgements. He was a conceptual type, unconcerned with the formal processes and procedures of military life and the obsession with details that it often entails. In his dealings with subordinates he was no authoritarian. But in the end, he called the shots.

His judgments were not infallible, but most of the time he was right. For, despite his unimpressive record at school, Grant was a man of formidable intellect. He absorbed large amounts of information very quickly. He read voraciously and acquired an encyclopaedic knowledge of military campaigns. He also had an eye for detail, but was very selective about which details interested him. His mind was constantly working on integrating and interpreting information, looking for patterns and boiling things down to their essence. His mind, it appeared to others, was never still. One observer noted his habit of whittling sticks with a small knife, and attributed it to a desire to occupy his hands whilst his mind was ‘all the while intent on other things’.

Though he was highly conceptual, Grant was not a theorist. His judgments were informed by common sense. Common sense drove logic. He could reason his way through a problem with very little information whilst others wanted to find out more. Logic combined with pattern recognition derived from experience enabled him both to make up his mind whilst others hesitated and remain comfortable with residual risk and uncertainty.

If these traits might be considered matters of disposition or character, Grant also possessed an acquired skill he honed to a very high level. It is not the first thing to come to mind in listing the core skills of the great commanders, but it is shared by all of them. Grant was a superb writer.

He wrote all his despatches himself, often at night, often at high speed, and all were concise and clear. One staff officer once observed of Grant’s orders that ‘no matter how hurriedly he may write them on the field, no one ever has the slightest doubt as to their meaning or even has to read them over a second time to understand them’. The note Grant penned to Buell at Shiloh was one such:

‘The attack on my forces has been very spirited since early this morning. The appearance of fresh troops on the field now would have a powerful effect both by inspiring our men and disheartening the enemy. If you can get upon the field, leaving all your baggage on the east bank of the river, it will be a move to our advantage and possibly save the day to us. The rebel force is estimated at over 100,000 men. My headquarters will be in the log cabin on top of the hill, where you will be furnished a staff officer, to guide you to your place on the field.’

For Grant as for most commanders, reliable information about the enemy was a rare luxury. The ‘estimate’ of the Confederate strength is out by almost 150%. It was actually closer to 40,000. Despite that, his decisions, and the actions they implied, were clear.

What Grant did

These characteristics, partly innate and partly acquired are just the foundation. What is more important is how Grant chose to act. His actions on that day at Shiloh exemplify patterns of behaviour which he and all the great commanders exhibit under almost all circumstances, but become critical when the situation is critical. The patterns in what they do, and what they do not do, set them apart from most.

As a leader, Grant gave good leaders support and encouragement according to their needs. Though he visited them all, he spent least time with Sherman, though his troops were raw and bore the brunt of the first attack, because Sherman needed the least help. Only when leaders failed did Grant step in and temporarily take over.

Despite that, one thing that Grant did not do was to issue rebukes or seek someone to blame for what occurred. He could easily have blamed his divisional subordinates for the lack of entrenchments. He chose to bear that responsibility himself. Instead of shaming failing subordinates, Grant focussed everyone’s efforts on getting through the day, for if they were to do so, they had to act as a team as they were, with weak members as well as strong.

That did not mean he did not notice. In the days and weeks that followed, commanders who failed were quietly side-lined. Those who stood the test of the day were given greater responsibilities, Sherman prominent amongst them.

In leading, the great commanders motivate people to do what is needed in the moment, build teams and develop other leaders.

As a manager, Grant defined priorities throughout the day, the first being ammunition, and delegated responsibility for execution. Even as his thoughts were on strategy, Grant still paid enough attention to critical operational matters to ensure that they were being properly attended to. In his memoirs Sherman observes that on the second day of the battle, cartridges ran out several times. ‘But,’ he adds, ‘General Grant had thoughtfully kept a supply coming from the rear’.

Having assessed what resources were available, he organised them, but in doing so he did not attempt to do the job of the level below him. He gave the job of creating the gun battery that defeated the final attack to one of his staff officers, Colonel J D Webster.

Other resources, he re-deployed. His cavalry were useless in the wooded terrain, so he formed them up in the rear to stop stragglers and send them back to the front as reinforcements. Some Confederate soldiers ran away too, but nobody on their side thought to do this, and so they were lost to their army. Grant found some use for everything he had. In a crisis, identifying and deploying all your resources is important.

But Grant also devoted effort to acquiring resources which were not yet available, not just to stabilise his front on that day, but to be ready for the morrow. At the same time as he was taking resolute action in the ‘now’, Grant had sufficient spare mental capacity to be thinking about his next move.

In managing, the great commanders make maximum use of all available resources, and gather more for tomorrow as well as today.

Which brings us to what Grant did as a director.

As he rode around during the day, he was integrating what he saw into an overall picture of the situation. He moved around more and so saw more than any of his subordinates did, but he also noticed things they didn’t and used patterns of experience to integrate them into an overall picture of the situation. Whilst others’ minds were completely filled with their own troubles, Grant also thought about what must going on on the other side.

Everyone was struck by the ferocity and determination of the Confederate attacks. But Grant noticed that most of the attacks were uncoordinated ‘dashes’, telling him that their units had become intermingled and their commanders were unable to direct them effectively. This lack of cohesion was a weakness he could exploit.

He knew that attacking troops become more exhausted than defending ones, that they would spend a cold, wet night in the open, and that it would be hard for them to be given food or ammunition. He saw to it that his men got both, and knew that he now had fresh troops available. It was a great opportunity to turn defeat into victory. He visited each of his subordinates during the night to make sure each one knew their part in his plan for the morrow.

That opportunity existed because he had taken time out to give calm, clear direction during the day. He was very clear about his main effort. First it was holding the centre, to buy time to shorten the line; then it was the defence of Pittsburg Landing; then it was deploying his reinforcements. What kind of crazy guy takes time to write a little note to one of his old college mates when his organisation is disintegrating in front of his eyes? A great commander.

In directing, the great commanders form a complete picture of the overall situation, grasp its essence, and use common sense and logic to decide what to do next

In his memoirs, Grant remarks that there was in fact ‘no hour during the day when I doubted the eventual defeat of the enemy’. As he steadily worked on building up an advantage, there was one thing he did not do. Give up.

After Shiloh, the northern press vilified Grant for being caught by surprise. There were stories that he was drunk and that Buell had saved the day. When Pennsylvania politician Alexander McClure visited the President late one night to demand that Grant be dismissed, Lincoln sat silent in his chair for a while before gathering himself up to reply: ‘I can’t spare this man. He fights.’

Others did not fight. Some fought and lost. Grant fought and won. He won because he was not just a great manager who understood logistics, nor a great leader who could inspire his staff and his men, nor just a great director who grasped the essentials of strategy — but a master of the trinity.