As change in the business environment accelerates, it requires the same of not only businesses but also their boards of directors. Given the increased variety of business environments and the growing importance of non-competitive forces, corporate strategy is increasingly complex — and also an increasingly important driver of performance. Furthermore, directors are facing increased calls from other stakeholders, including management and investors, to be more deeply involved in setting strategy.

However, the current reality is that the extent and manner of engagement in strategy still varies widely from board to board. What benefits can directors bring to the table, and what are the best practices of forward-looking companies when it comes to the board’s role in strategy?

Strategy Is Increasingly Important

Corporate strategy is increasingly challenging for today’s leaders. Business environments are becoming more and more varied, which requires companies to actively choose strategic approaches that match their own specific situations. External forces such as political pressures, social expectations and macroeconomic circumstances are having greater impacts, adding to the complexity of strategy. And the increasing pace of change means that strategic assumptions must be re-evaluated constantly.

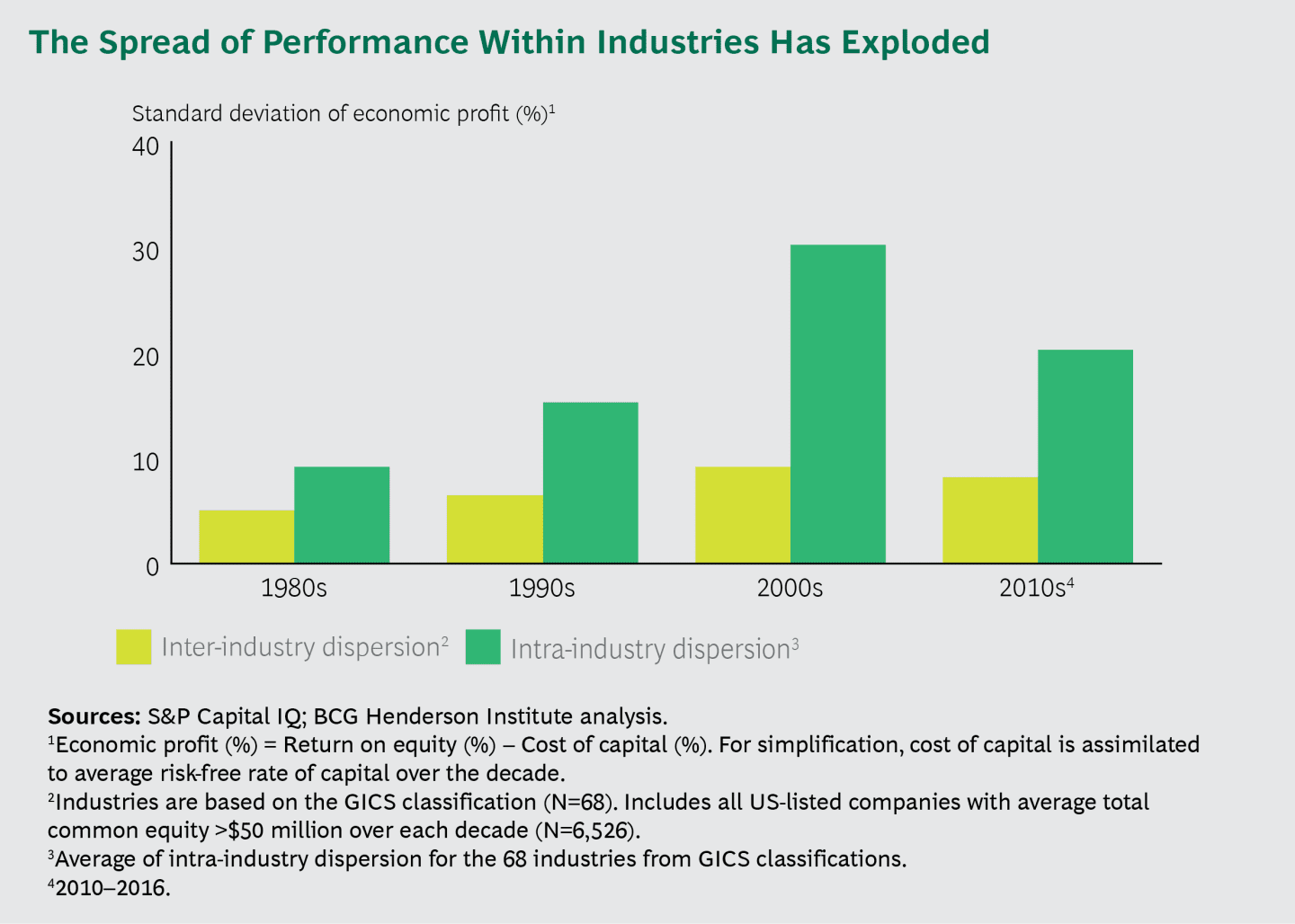

At the same time, corporate strategy is also becoming more important. With aggregate growth trending downward globally and new competitors presenting a constant threat of disruption, companies can no longer count on merely extending and exploiting historical strategies over the long term. This means that strategy has become a more important source of differentiation between firms: Within a given industry, the average dispersion of performance has doubled since the 1980s. (See Exhibit 1.)

Given the growing importance and complexity of strategy, other stakeholders are demanding that directors focus more on the topic. For example, the leaders of Vanguard, Blackrock and State Street (the three largest shareholders of U.S. corporations) have all publicly called for boards to be deeply involved in setting strategy within the last year.[1]Vanguard Chairman William McNabb’s key questions for CEOs for the Strategic Investor Initiative (February 2018); Blackrock CEO Larry Fink’s open letter to CEOs (January 2018): State Street Global … Continue reading

In the past, shareholder activism has generally been associated with financial engineering and other actions with an immediate payoff. However, passive investors, which have long term holdings and do not benefit from any short-term value creation that is not sustained, account for an increasing share of ownership. This suggests that we should expect an increase in a new type of shareholder activism, focused on corporate strategy and issues with long term impact. (Indeed, a majority of institutional investors already say the most important factor in supporting activist campaigns is a “credible story focusing on long-term strategy.”[2]“Institutional Investor Survey 2018”, Morrow Sodali https://www.morrowsodali.com/attachments/1517483212-IIS_2018_final.pdf) Accordingly, directors must make sure they are attending to strategic issues responsibly.

Similar demands are not limited to investors: Nearly all CEOs also say that their boards should spend more time on strategy. Based on the business environment and the beliefs of other stakeholders, board members have a clear mandate to become more involved in strategy. So why is this often challenging in practice?

Board Involvement Is Challenging, But Can Add Substantial Value

At first glance, it sounds like a trivial observation that boards should be highly involved in corporate strategy. Directors themselves recognize the need: Collectively, they rate long-term strategic planning as the top issue demanding attention by the board.[3]“What Directors Think”, NYSE/Spencer Stuart (2016) https://www.nyse.com/publicdocs/WDT_Report_2016.pdf

The fact is, however, many boards are ill-equipped to deal with strategy in the modern environment. They may not have the appropriate expertise: Many directors at incumbent companies built their careers in a “classical” business environment, and may not have proven capabilities to master the variety of strategic approaches that are required today.

Furthermore, directors typically have many different roles and competing commitments, limiting their available time and energy. Their legal mandates center on topics like audit, compensation, and governance. Regulatory changes, such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, have increased their focus on compliance. And new risks, including cybersecurity, data privacy, and harassment, are drawing more attention from boards. These demands can collectively crowd out directors’ attention to strategy.

As a result, there is wide variation in board engagement in strategy. On one end of the spectrum, some may lean toward a less active role: For example, more than half of directors said that management, rather than directors, is responsible for identifying potential strategic disruptions at their company in a recent survey.[4]NYSE/Spencer Stuart, “What Directors Think” (2017) http://boardmember.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/WDT_Report_2017-1.pdf Yet at the other end of the spectrum, some boards have a very hands-on approach: In the same survey, a small minority said they have a separate board committee that studies disruption risk.

Boards can add significant value by focusing on challenging and shaping strategy in a number of ways:

- Focusing on the long run to complement management. Management often has a tendency to focus on the short-term picture. This is understandable — and necessary — given that running the business presents constant challenges. (CEOs themselves recognize this tendency: 86% say they focus more on short term than the long term.[5]CECP Board of Boards, Executive Report (2016) http://cecp.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/BofB16_Executive_Summary_FINAL_Web.pdf ) But for the firm to remain vital over time, it must also pay attention to the future. By sitting outside the day-to-day operations, directors are in an ideal position to counter-balance management’s tendencies and focus on the long run — enabling the firm to act strategically on multiple timescales.

- Leveraging embeddedness. The impact of external forces on business is increasing. Reflecting this, our research shows that companies discuss political and economic factors more frequently than ever in their annual reports. Board members can uniquely use their external connections to understand the broader picture and use it to help build a resilient firm. By leveraging their different backgrounds, as well as their connections to other stakeholders through concurrent involvement in different businesses or industries, directors may be able to detect emerging threats or opportunities more quickly and ensure that the firm responds accordingly.

- Contributing cross-domain insights. As industry boundaries are blurred by new technologies and business models, sector-specific knowledge is no longer sufficient. Given the risk of digital disruption, leadership must be informed about emerging technologies and new competitors. When selected thoughtfully, directors can fill gaps in management’s skills or knowledge in key areas.

- Governing firm strategy and execution. Given the increased stakes and complexity of strategy, its governance is more and more important. Boards are in a unique position to pressure-test management’s decision-making, ensuring that the strategy is tailored to each business environment and continually probing key assumptions to make sure they remain valid. Furthermore, directors can use their role to monitor execution of the strategy, and ensure it is being carried out properly.

Together, these actions transform the board’s engagement model for strategy well beyond a “rubber stamp.” Instead, boards should take an “activist” approach and think about how to challenge and disrupt their own strategy — before an actual activist (or competitor) does so.

Strategic Focus Requires a New Board Model

As the strategic demands of directors evolve, so too do their required skills. A board that is drawn from a homogeneous industry or financial background will leave some strategic benefits on the table. Where possible, firms should aim to select directors with a variety of relevant skills, which may include technological knowledge or political expertise.

Yet at the same time, boards must balance the risk of becoming too bloated, and therefore unable to effectively make decisions and provide governance. According to our research of large U.S. firms, companies with larger boards have lower average growth over the following five years even when controlling for relevant factors such as company size and age. This relationship is not limited to any one industry in particular (e.g. tech companies), and it is statistically significant and predictive of future growth.

Therefore, boards should not attempt to check off every possible box of expertise, especially in emerging areas such as cybersecurity, where finding directors with legitimate skills is very difficult. Instead, management and the board should regularly seek advice from independent experts who are more up to date with new developments in these fields. This way, leadership can recognize and address any gaps in its thinking — perhaps in the form of information on new technologies, or perhaps through a different viewpoint on the firm’s strategy as a whole. For instance, directors might ask a successful tech entrepreneur, “How would you disrupt our company?”

Best Practices of Highly Involved Boards

How can companies build boards that are capable of effectively shaping strategy?

1. Board meetings feature a range of ideas and viewpoints. Directors themselves should represent a diversity of perspectives to improve the group’s collective decision-making. Gender and ethnic diversity certainly help in this regard, but they are not enough: Additional sources of heterogeneity — such as age, industry or educational specialties, and international experience — also increase the potential range of innovative ideas.

Diversity may be an obvious goal, but is often elusive in practice. A recent study indicates that directors with similar backgrounds (male, financial experience, served on other boards) remain overrepresented today, with negative impacts on firm performance.[6]“Research: Could Machine Learning Help Companies Select Better Board Directors?” (HBR, 2018) https://hbr.org/2018/04/research-could-machine-learning-help-companies-select-better-board-directors This does not mean that companies should try to “check every box” of representation, which risks a bloated and ineffective board. However, they should ensure that a variety of viewpoints and backgrounds are always represented.

Board meetings should regularly involve external experts, adding fresh perspectives that can be tailored to the most pressing issues. To ensure that outside voices are integrated into the strategic process, directors should also be chosen for their ability to engage in productive debate — for example, being receptive to new views, challenging others’ ideas in a constructive manner, and being motivated to engage in strategy deeply and collectively.

2. The board challenges management adeptly — and management is receptive to challenge. No matter how capable the executive team is, an external perspective can always help ensure the strategy is more robust. However, board members may have difficulty asking the tough questions — perhaps because they do not know what or how to probe, due to information asymmetry; or perhaps because they do not want to appear disruptive. (This is a long-standing problem: As Warren Buffett wrote thirty years ago, “At board meetings, criticism of the CEO’s performance is often viewed as the social equivalent of belching.”[7]1988 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report) And some CEOs are less receptive to challenges, perceiving tough questions as hostile.

To avoid these pitfalls, directors must act as “loyal critics,” mastering the art of challenging management while preserving trust. This starts by building a working relationship outside of formal meetings, so directors know what issues to focus on and the CEO is prepared to engage productively in the process. Then, the board should ask challenging questions — ones that make critical hidden details explicit by foregrounding strategic assumptions and essential features of the broader context. Examples of probing questions include:

- What are plausible scenarios for the future of our industry?

- Will our strategy be robust to changes in the macro environment?

- What are the sensitivities of key assumptions?

- How do you ensure adequate implementation of the strategy?

- Do we have the right talent to execute it, for now and the future?

- What are the potential downside risks and mitigation plans?

The board and management should iterate until these questions are answered with sufficient clarity and precision. To ensure every decision receives thorough scrutiny, directors might institute a rule of “compulsory dissent”: No strategy may be endorsed until at least one robust counterproposal has been explicitly offered and considered.

3. Directors monitor execution of the strategy. Execution cannot be separated from strategy — they are intertwined. Just as the approach to strategy should be modulated according to the environment, so too should the approach to execution. The board can play a vital role in ensuring that strategy is implemented throughout the organization, but it can be difficult in practice: According to a National Association of Corporate Directors survey, 67% of directors say it is important to improve their monitoring of strategy execution.

Effectively monitoring strategy execution is not as simple as watching a dashboard of results. The board should make sure that management is evaluated on both financial and non-financial dimensions, with a clear prioritization of metrics in line with the firm’s overall goals. This avoids the pitfalls of an excessively long list of measurements, in which a few good ones can be highlighted while others are explained away or overlooked.

Additionally, directors should meet with management frequently to test that the original assumptions behind the strategy still hold. Follow-up meetings should involve not only the CEO but other layers of management, ensuring that strategy is being implemented throughout the entire organization. These can be complemented by employee surveys to understand the execution in even more detail. For example, during a large transformation, the board might identify where in the organization employees do not understand the strategy, do not see progress in the change effort, or do not believe they have sufficient resources to implement it.

4. Boards dedicate more time to strategy and keep discussions focused. Given directors’ other responsibilities and the infrequent nature of board meetings, it is challenging for them to stay up to date on key trends and continuously validate the firm’s strategic direction. Though directors say they want to spend more time on strategy, the reality is that instead they are increasing their time spent on other topics, such as governance and risk.

To ensure sufficient focus on strategic topics, boards should schedule dedicated time to discuss strategy in the agenda of every board meeting — not only on an annual cycle. Furthermore, a robust knowledge system can give directors the information they need: Frequent updates should keep directors apprised of changes in the environment and resulting impacts on firm strategy. Extensive communication before and after board meetings can streamline the sessions themselves, freeing up time for strategic discussion. And directors should have access to a repository of on-demand materials to increase their inside knowledge of the company.

Time and information alone are not sufficient, however: Even when time has been carved out for strategy, the discussion often devolves quickly to more familiar territory, such as granular details or the firm’s current operations. For example, if the board intends to discuss marketing strategy, it may soon find itself focusing on sales strategies instead, and eventually questioning the firm’s practices in managing a sales force. These discussions may yield useful suggestions, but by ignoring the bigger picture, they represent a missed opportunity for the board to add even more value. The best board chairs can keep discussion focused on key strategic issues — a very difficult task, but one that is crucial.

A changing business environment calls for an enhanced role of directors in relation to strategy. Strategy is becoming more challenging yet more important, increasing the value of boards that can actively partner with management and guide the company’s future direction. By practicing “self-activism” — challenging assumptions, offering counterarguments, and closely monitoring execution — boards can help develop a strategy to succeed in the modern age.