No company is an island. This has never been more apparent than it is today. Business is more vulnerable than ever to political forces, economic upheaval, and social change. Consequently, the view of public companies as standalone machines to be optimized to deliver the highest possible short-term returns to shareholders is increasingly untenable. Rather, as participants in complex adaptive systems — in which outcomes are shaped by interactions among members — companies need to fulfill a purpose that is beneficial to those systems.

This requires a departure from the insular models that underpin traditional management thinking, epitomized by the narrow goal of maximizing total shareholder returns in the short term, toward a mindset that considers the impact of strategies and actions on broader systems. Think of it as a shift from a mechanistic to a more humanistic view of the corporation.

Interestingly, Aristotle advocated this perspective more than 2,000 years ago. He argued that wealth maximization as an end in itself is likely to undermine society and must instead be directed toward a higher purpose — a purpose that is in line with larger goals related to the welfare of all. In fact, our research leveraging natural language processing (NLP) shows that firms pursuing such a purpose have been rewarded by faster growth, higher employee engagement, and, paradoxically, superior financial performance. We suggest some principles of a strategic agenda that leaders can follow to humanize their companies in ways that generate benefits for both the business and the broader system.

The limits of the TSR-maximizing machine

In complex adaptive systems, local interactions can give rise to unpredictable global effects, which in turn shape local interactions. Companies are themselves complex adaptive systems. They are also nested within larger systems: companies are part of business ecosystems that are embedded in local and national economies, which in turn are interwoven with societies. The recent political tide against global economic integration is an example of an intersystem feedback effect. It could soon be compounded by another: the emerging backlash against technology, motivated by fear of its impact on employment and equality.

A root cause of the negative feedback to two major drivers of economic growth — globalization and technology — can be traced to the mechanistic mindset that prevails in many corporations. The goal of maximizing short-run TSR can easily lead to the dehumanization of business: companies can be stripped of human qualities and run as short-term extractive machines to maximize their own financial benefit, without giving adequate consideration to spillover effects on broader systems. This risks alienating internal and external human stakeholders, whose actions are influenced by values, not purely by financial self-interest. A study by ManpowerGroup showed that the top career priority for more than 40% of millennials is not to maximize earnings but to make a positive contribution to society or to work with great people.

The pursuit of narrow goals has contributed to several negative feedback effects:

- Disengagement in the workplace, with only 33% of US employees feeling engaged

- A mistrust of business, reported by 42% of Americans

- Inequality between winners and losers, and the political and economic repercussions of that, as the top 1% of the population in the US takes home more than 20% of the income

These trends could be reinforced as companies look to deploy technology primarily to cut labor costs. Fear of unemployment could increase the popular mobilization against technology, impairing companies’ ability to innovate and grow.

To survive and thrive under such circumstances, corporate executives should expand their focus beyond their companies’ immediate profits and consider the impact of their strategies and actions on broader systems.

Rethinking purpose

Businesses enjoy a social license that is based on the assumption that they respect the rights of those affected by their activities. This license gives management virtually unrestricted freedom to set whatever goals it deems appropriate. Some CEOs have used this freedom to pursue initiatives that can have a positive impact in the world, but others have focused on the goal of short-run TSR maximization, leading to frictions with society. As Tom Wilson, the CEO of Allstate, explained, “There’s no reason corporations have to exist in history. To the extent we don’t live up to their expectations, people can revoke those rights, levy harsher taxes, summon more regulations, or, in a bleaker scenario, change the corporate framework entirely.”

The challenges that arise from a sole focus on short-run TSR maximization were anticipated by Aristotle, who distinguished between two kinds of economics. The first is chrematistike (from chrema, money), or wealth maximization as an end in itself. Chrematistike (in our context, short-term TSR maximization) is arguably appropriate under two conditions: first, that there are minimal negative externalities affecting systems beyond the company; and second, that the game is established enough that the emphasis on exploiting it makes sense, but not so mature that the exploration of new possibilities has become an urgent necessity. Clearly, these conditions do not hold today — consider the conspicuous externalities of climate change and inequality, to mention but two, and the urgent need for companies to reinvent themselves in response to rapidly evolving technological and social conditions.

According to Aristotle, a second, and superior, kind of economics is oikonomia (the art of managing the household, from oikos,house, and nomos, rule), which subordinates financial considerations to the higher purpose of family welfare. As he described it, “The art of household management must either find ready to hand, or itself provide, such things necessary to life, and useful for the community of the family or state.” To ensure survival in the long term, companies must fulfill a goal that serves the larger system. Failure to do so puts them at risk of being gradually starved of the support they need from other system participants.

Focusing on ESG (environmental, social, and governance) issues and CSR (corporate social responsibility) may not fully address the problem if such efforts are intended primarily to limit negative spillover effects. While some companies have embraced ESG and CSR as a fundamental shift, for others these approaches are merely additional factors to be considered when trying to maximize TSR. In particular, an ESG or CSR agenda doesn’t necessarily plant the seeds of broad-based prosperity gains because it doesn’t necessarily push companies beyond their own narrow interests.

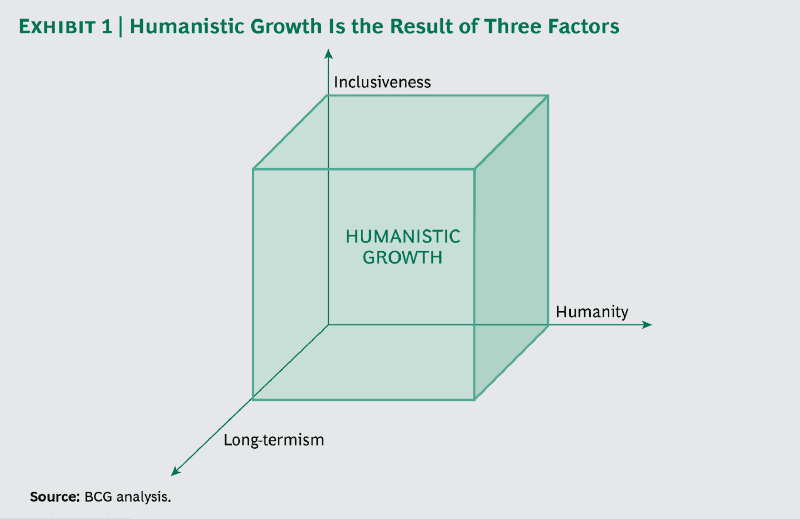

To renew the social license companies currently enjoy, the focus on maximizing short-term results should be balanced by factoring in the long-term implications of current decisions, defining a purpose aligned with human ends, and setting objectives that are inclusive. (See Exhibit 1.)

Recent political events around the world have been shaped in large part by frustration with economic stagnation and inequality: 70% of the US workforce has experienced no real wage increase in the past four decades, and the English West Midlands, the region with the highest number of “leave” votes, has experienced stagnating median household incomes for nearly two decades. Similar patterns can be observed in Canada, Germany, and other European countries. Companies’ strategies and actions can magnify these inequalities or shrink them by ensuring that the gains of economic activity are distributed equitably.

The change in mindset requires companies to move from the quantitative maximization of one goal (chrematistike) to the qualitative optimization of multiple goals (oikonomia). Companies that make this shift place themselves at the intersection of a need in the world and a distinctive aspiration and ability to address it. We call them human companies.

Measuring the character of corporations

To test the idea that human companies produce better outcomes, we developed a methodology to measure the essential character of companies. Language is a defining human feature, enabling us to express our values, intentions, and character. Companies use language, too, and we can assess their character by leveraging natural language processing (NLP) technology. Using nearly 100,000 company filings from 2005 to 2016, we developed an algorithm to detect semantic fields around keywords reflecting companies’ orientation toward TSR maximization (chrematistike) or higher purpose (oikonomia). We controlled for instances of insincerity by considering the consistency, volume, and diversity of data. In particular, our analysis excluded companies with excessive variation across data sources, which we took as an indication of attempts to paint a different picture to different audiences.

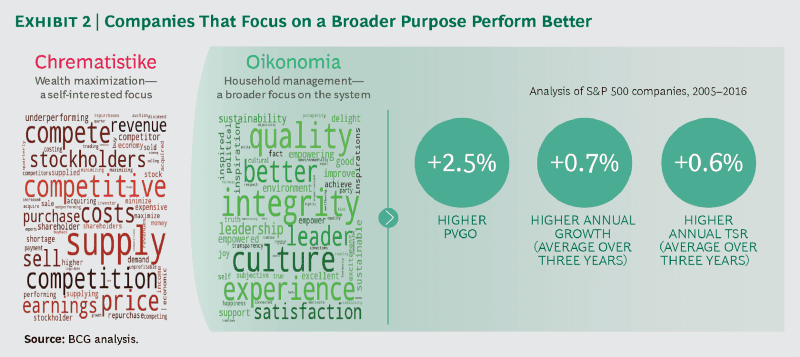

Unsurprisingly, results show that more than half of the companies we analyzed seldom use the language of oikonomia — words such as “integrity,” “culture,” “mutualism,” and “contribution.” Overall, corporate language remains dominated by words aligned with chrematistike, such as “competitive,” “earnings,” and “stockholders.” But we discovered that some companies repeatedly and consistently put more emphasis on words associated with oikonomia.

Our research found that some of the differences in the language companies use can be explained by their industry. Unsurprisingly, businesses that do not serve individuals have less orientation towards oikonomia. We also observe that younger companies tend to use more human language. But even adjusting for age and industry, companies differ markedly in their humanity. Pursuing oikonomia is a choice each company can make, and those doing it are consistently rewarded. Because human companies focus on a broader set of objectives, they tend to score better on nonfinancial metrics: they record higher engagement, better ESG scores, and more diversity among top management. Paradoxically, they also have better financial performance: 0.7% higher growth per year and 0.6% higher annual TSR (both over a three-year period), and 2.5% higher PVGO (present value of growth options). (See Exhibit 2.)

Rewriting the strategic agenda

How should companies change their mindset and rewrite their strategy agenda to focus on a broader purpose? We suggest eight steps:

Define your purpose, the higher social goal of your company.This should be at the intersection of a need in the world and a distinctive aspiration and ability to deliver it. Crucially, companies then need to take actions consistent with their stated purpose, even when they might appear to impair short-term results. Consider CVS Health, the first US retail pharmacy chain to stop selling tobacco products. The company made this move in keeping with its purpose of “helping people on their path to better health.” This led to a nationwide decline in cigarettes sales.

Adopt metrics that assess the well-being of the broader system. Such metrics can include, for example, a focus on inclusiveness and equality. The pharmaceutical company Merck launched a program in 2010 with the goal to make its drugs available to 80% of the world’s population. The company employed a number of levers to achieve this, some with direct application to the business and others that could be targeted at specific markets and products. For example, Merck has made changes in packaging, distribution, and storage to ensure that its products can reach patients in developing markets.

Put more emphasis on the future. As our research has shown, in order to keep growing companies need vitality — the capacity to explore new options, renew strategy, and grow sustainably. Today, large, established companies are increasingly vulnerable because of their inability to create a sufficient portfolio of growth opportunities. Unilever CEO Paul Polman strongly believes in the need to balance the short and the long term when defining corporate strategy, and to adequately invest in the future of the company. “You cannot create long-term value if you’re not able to grow your business,” he notes. “You can’t save your way to prosperity.” This approach has been consistently rewarded by superior financial performance: during Polman’s tenure, Unilever has overperformed both its peers and the broader market.

Invest in technology “front to back.” That is, stress growth and the fulfillment of unmet human needs, rather than the easier prize of cutting costs (and often jobs) in the back office. Some basic needs, such as education, health care, and housing, have become more expensive, and the cost burden has often fallen disproportionately on the less fortunate. Nvidia CEO Jen-Hsun Huang believes that “there has to be a connection between the work you do and benefits to society” for companies to be successful. When he realized that Nvidia’s machine learning platform could play a crucial role in improving patient outcomes, he teamed up with leading health care solutions providers to bring AI to medical imaging. Ultimately, Nvidia’s goal is to improve the reliability of disease detection, diagnosis, and treatment. While this will undoubtedly be a major growth driver for the company, it will also benefit millions of people.

Reeducate employees and citizens to make them better equipped to deal with changes wrought by technology. This would both reduce unemployment and alleviate talent shortages in emerging areas such as data engineering and artificial intelligence. For example, Google aims to improve the lives of as many people as it can by leveraging its unique digital skills. The company is backing this up with various initiatives to create more opportunities for people, including Grow with Google, which aims to address the shortage of digital skills by offering self-learning tools and certifications.

Rethink and reshape the future of work. In particular, understand and redefine the role of employees in organizations powered by AI so that the technology can take over mundane tasks and free up time for more rewarding activities. One of the key changes millennials are introducing to the workplace is their preference for flexible work schedules to improve their work-life balance. Technology can play a key role in this regard. One example is Shiftgig, a centralized marketplace that connects people to shifts on a mobile device. As cofounder Eddie Lou explains, “Shiftgig collects hiring manager requirements, worker skills, and mobile data to enable smarter and more-timely matches. Workers select shifts on their terms, choosing when, where, and for which top local employers they want to work. Hiring managers get a technology-powered solution that helps them manage business growth and seasonal labor challenges quickly and reliably.” The gig economy sometimes is portrayed as comprising insecure, unattractive jobs. In fact, the majority of the gig economy consists of autonomous knowledge workers. The role of the gig economy is what we engineer it to be.

Support entrepreneurial business ecosystems. Corporations should rethink their global supply chains and business models in ways that create demand for the services of new and small companies. Among its values, Starbucks states to be “performance driven, through the lens of humanity.” The humanity of the company is evident in Starbucks’ supplier structure, which comprises hundreds of growers that share the goal of sustainable production. To incentivize the pursuit of such high standards, Starbucks has developed specific trainings to help sustainability-oriented farmers — whether they are suppliers of the company or not — improve both the quality of their crops and their profitability. Mindful of the higher cost of sustainable production, Starbucks has also created the Global Farmer Fund program, which provides financial assistance to help ensure the sustainability of the specialty coffee industry.

Communicate a compelling new narrative for globalization, technology, and business overall that will inspire confidence in a shared future. Narratives can shape perceptions and political reality, which in turn can shape economic reality. Business leaders have the opportunity to take an active stance and shape collective understanding. In the face of popular backlash, companies should communicate a narrative demonstrating that business and technology are contributors rather than obstacles to human ends.

Becoming a human company is a long journey. Once companies articulate their purpose, they need to understand their starting point and ensure they are well equipped for the change. Business leaders willing to change their company’s character and guide the transformation could help usher in a new era, in which the widespread emergence of human companies, able to plant the seeds of inclusive growth and remain vital by constantly innovating, could lead to broad-based prosperity gains for society and a long-lasting future for those companies.