We tend to think of innovation as something an organization does internally using its resources, capabilities, and processes in a highly structured manner. Most large organizations build dedicated departments for innovation, such as Amazon’s Lab126 or Alphabet’s X moonshot factory. Leading consulting and professional service firms invest in thought leadership units, such as BCG’s Henderson Institute or the McKinsey Global Institute. This planned approach to innovation is how most established organizations try to expand the envelope of their businesses. Despite its dominance, however, it is not the only path. Focusing efforts on this structured, internal approach downplays other crucial routes to innovation.

Some organizations augment the classical internal approach by inviting ideas and new thinking from outside. For example, Shell’s Gamechanger, 3M’s lead user innovation, or the Lego Ideas programs. These are initiatives designed to bring ideas developed externally or collaboratively within organizational boundaries to develop them further using the expertise and resources of the organization. For more targeted challenges, organizations may crowdsource solutions using platforms like Eli Lilly’s Innocentive. Such open innovation[1]Chesbrough, H.W. & Appleyard, M.M. 2007. “Open innovation and strategy,” California Management Review, 50(1): 57–76. or open strategy[2]Stadler, C., Hautz, J., Matzler, K. & von den Eichen, S.F. 2021. Open strategy: Mastering disruption from outside the C-suite. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. initiatives can cast a wide net and bring in fresh thinking from groups of stakeholders who are not normally consulted deeply on innovation matters. Organizations can do a lot to foster creativity by encouraging and allowing for access to diverse building blocks of innovation[3]Fink, T.M.A. & Reeves, M., 2019. “How much can we influence the rate of innovation?” Science Advances, 5(1), eaat6107. by opening up to external inputs in this way. Indeed, corporate “vitality” (the potential for future growth) is predicted by, among other things, an externally oriented culture.[4]Reeves, M., Krupa, M. & Job, A. 2023. “Vitality: A Unique Lens for Understanding Companies’ Growth Potential In Turbulent times.” … Continue reading And the science of imagination suggests that it is triggered by surprise and pattern breaking, which will be more frequently encountered by extroverted organizations[5]Reeves, M. & Fuller, J. The Imagination Machine, Harvard Business Press, June 2021. than more conservative introverted ones.

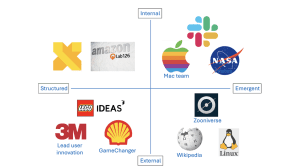

As an alternative to a traditional, highly structured approach to innovation, we also need to consider approaches that are more emergent, social, serendipitous, and interactive.[6]Reeves, M. & Goodson, B. 2025. “What the like button can teach us about innovation,” Harvard Business Review, May–June. Available at: … Continue reading The figure below shows four paths to innovation, based on degree of structure versus emergence, and the source of ideas being internal or external. These form four quadrants that are very different but complementary paths to innovation.

Looking at the internal and emergent quadrant on the top right, unplanned initiatives can grow to become field-shaping innovations. Slack, the viral collaboration software, was created in 2009 by engineers in a small startup called Tiny Speck, which was at the time developing a virtual game called Glitch that ultimately failed.[7]Clark, K. 2019. “Slack origin story: How a whimsical online game became an enterprise software giant,” Techcrunch, 30 May 2019. Available at: … Continue reading Slack, or “Searchable Log of All Conversation and Knowledge,” was created for the engineers’ own use, to solve the problem of collaborating with colleagues across countries and time zones on a variety of interconnected tasks. When it was clear that Glitch would not work, it was killed in 2012. The company realized, however, that they had created something powerful in Slack and pivoted to launch it as enterprise collaboration software in 2013 as the company’s main product, rebranding the company as Slack Technologies.

Innovation initiatives in this quadrant can also arise from individuals who see weak signals on where the market is headed that may be missed by formal processes, or who are driven by imaginative visions of the possible. These people are often seen as being unrealistic or as rebels and troublemakers. But such mavericks are a precious source of diverse thinking, intellectual courage, and pattern breaking, which is crucial to the long-term prosperity of organizations. The NASA pirates, who invested years to build a new mission control for the agency without being asked to do so, simply because they believed it was necessary, are a prime example,[8]Heracleous, L., Wawarta, C., Gonzalez, S. & Paroutis, S. 2019, “How a group of NASA renegades transformed mission control,” MIT Sloan Management Review, 5 April, … Continue reading and so are the engineers who developed Toshiba’s word processor and laptop computer below the company’s radar.[9]Abetti, P.A., 1997, “Underground innovation in Japan: the development of Toshiba’s word processor and laptop computer,” Creativity and Innovation Management, 6(3): 127–139. The first MacBook was developed by a few committed Apple employees in a makeshift space over a gas station, away from the company’s red tape. Such “underground” innovations can emerge because committed individuals see a better way to address a work challenge, change how an organization does things, or are passionate about realizing new possibilities.[10]de Jong, Jeroen P.J., Mulhuijzen, M. & Prasad, K.V. 2023, “Mining underground innovation,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring, 50–55.

The most underappreciated and neglected quadrant of innovation, however, is on the bottom right. This is where emergent innovation occurs outside the organization. The building of Wikipedia and Linux operating systems, for example, indicate that exceptional things can be created if individuals see them as worthwhile and see a bigger purpose in making a contribution. Zooniverse, the citizen science platform that involves 3 million volunteers, has made impressive contributions to knowledge in terms of publications and scientific discoveries such as new celestial bodies and neural circuits.

The development of the ubiquitous “like” button[11]Reeves, M. & Goodson, B. 2025. Like: The button that shaped the world. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press. is a prime example of external, emergent innovation. It emerged not from a formal project in the innovation department of a large company, but rather from the collective efforts of numerous small enterprises. Early social platforms were already exploring micro-interactions two decades ago. Vimeo introduced a “like” button in 2005, inspired by the “Digg” button of Digg.com. FriendFeed then introduced a “like” button in 2007, before being acquired by Facebook in 2009. At Facebook, the “like” button was eventually championed by small informal teams at a time when top leadership was firmly against the introduction of a “like” button. Once introduced by Facebook however, the button quickly became a transformative feature not only for the company but also for social media and advertising industries and eventually the internet as a whole.

What does the neglected quadrant mean for organizations? For incremental innovations that are somewhat plannable and well within the scope of a company’s knowledge and capabilities, other quadrants may suffice. But to tap into the most imaginative and transformative possibilities, companies need to harness the power of collective intelligence and serendipity. Beyond investing in their own R&D, companies must be open to boundary-spanning innovations that may draw from customer behaviors, business ecosystems, or competitor/collaborator experiments. And structure must not supress the emergence of the unexpected. Serendipity is not randomness however. The chances for serendipitous discoveries can be maximized by creating the right conditions, through facilitating access to new ideas, resources, and interactions,[12]Fink, T.M.A., Reeves, M., Palma, R. & Farr, R.S. 2017. “Serendipity and strategy in rapid innovation,” Nature communications, 8(1): 2002. from wherever they may arise.