Chegg, the homework help platform, is the first prominent victim of ChatGPT, losing more than 99% of its value last year since its peak in 2021. Chegg’s story is the story of how chasing fleeting trends building enduring advantage can leave you rudderless when change strikes again.

During COVID-19, Chegg experienced an unexpected surge in usage as remote learning became the norm, with subscriptions reaching record highs and Chegg’s stock price following suit. Chegg rode the wave up, enjoying the transient advantage it bestowed on its business. Students stuck at home took to the platform in their masses. But just as the Covid swell receded, the next wave – new generative AI tools – came crashing in. Chegg’s subscriber base quickly plummeted, and the value of their paid-for subscription model became increasingly unattractive next to tools like ChatGPT, which were easier, quicker, and cheaper to access. The shift left it squarely in a disadvantaged position.

Contrast this with the story of TI-82, the graphing calculator invented by Texas Instruments in 1993. The TI-82 has resisted three successive and significant waves of disruption – the rise of personal computers, the rise of smartphones, and the rise of generative AI. Despite huge technological leaps since its inception, the TI-82 continues to dominate in the American classroom even as cheaper more powerful alternatives proliferate.

Chegg’s pursuit of fleeting, transient advantages left it vulnerable, while Texas Instruments somehow forged a competitive advantage that endured market shifts.

The paradox of stability vs change

How are some companies able to build enduring advantages, while others become stuck chasing a fragile cycle of transient wins?

Some respected strategist like Roger Martin and Julian Birkinshaw have insisted that disruption is overplayed and that companies with strong foundations can thrive over decades. Others like Rita McGrath argue that competitive advantage is increasingly fleeting – that firms must constantly reinvent themselves to survive, and must constantly renew temporary advantage.

Both seemingly opposing positions can be backed with quantitative evidence – churn in company rankings on the one hand and the persistence of long-lived companies, despite disruption, on the others.

The stability school argue that once a company builds a dominant position, it can maintain its lead through persistent scale economies, network effects, and brand loyalty. Some of the world’s largest firms – the Big Tech titans – have indeed sustained and grown their dominance over nearly three decades now, demonstrating the power of sustaining advantages. More broadly, industry concentration has been on the rise since the early 2000s, with over 75% of U.S. industries seeing an increase in concentration levels and the top four firms in most sectors expanding their market share. [1]Grullon, G., Larkin, Y., & Michaely, R. (2019). Are U.S. Industries Becoming More Concentrated? Retrieved from SSRN.

But scale isn’t destiny and business history is littered with incumbent firms which failed, were eaten up or stagnated and declined. The churn rate of companies in the S&P 500 has accelerated dramatically over the past few decades in the face of external shifts. Dramatic examples of disruption are not hard find. Companies that hold their position don’t do so by sitting still, it is argued. Rather, they adapt in the face of changing circumstances.

How do we resolve this apparent paradox?

Reconciling the paradox

At first glance, these two narratives seem incompatible. But the truth is more nuanced: stability and adaptation aren’t actually opposing forces and can co-exist to cultivate advantage. Stability without adaptation leads to obsolescence, while perpetual change without lasting advantage leads to unnecessary complexity, cost and even commoditization. The real challenge isn’t choosing between them, but rather understanding how they work together.

The widening gap between firms that expand their advantages and those that barely hold on isn’t explained by who adapts faster. It’s explained by those who understand when and how to adapt, so as to transmute change into lasting advantage. These firms use instability to craft a path towards a new stability.

This relationship between change and stability is very easy to misconceive in one of two major ways.

1. Misreading change

NBA teams used to build their strategy around dominant big men and mid-range shooting. That was till Stephen Curry and the Golden State Warriors came in and rewrote the play. They shifted the game to three-point shooting and built an entire system around it – stretching defenses, prioritizing spacing, and moving the game beyond traditional positions. The teams that adapted – Houston, Milwaukee, even LeBron’s Lakers – stayed competitive. The ones that didn’t, like the early 2010s Knicks and Lakers, found themselves playing a game that no longer worked. The winners had recognized the game itself had changed.

In business, as in basketball, companies can misread what’s happening and stay stuck playing a game that no longer matters. Traditionally, businesses dealt mainly with operational uncertainty, which exists within a known structure, where the fundamental “rules of the game” remain stable. Operational uncertainty involves unforeseen challenges within a stable game – companies may have to adjust strategies and tactics, but the playing field – and, more importantly, the game they are playing – remain familiar. Confronted purely with operational uncertainty, Yahoo would still be dominant.

Today, however, companies are faced with a far more challenging problem – structural uncertainty. Structural uncertainty reshapes the entire playing field itself, and with that, you can easily be left playing the wrong game. This type of uncertainty doesn’t just change how companies compete – it changes what they are competing for or against. Think of Kodak watching Fuji as its biggest rival – while digital cameras, then smartphones, then Instagram, wiped out the traditional photography industry.

In the past, these structural shifts occurred but were rare. Mass production replaced craft-based manufacturing – a once-in-a-generation transformation. But today, these types of shift occur more frequently and faster. Cloud computing, smartphone connectivity, the rise of the social web, improvements in big data management collided to birth today’s platform economy. And things haven’t stayed still since.

2. Misunderstanding what we should aim for

The second misunderstanding involves the nature of the advantage itself. Temporary or transient advantages arise from reacting to short-term shifts, riding a temporary wave (like the COVID-19 surge in demand for Chegg). These advantages of timing are short lived because of fleeting circumstances, and rapid imitation.

Enduring advantages in dynamic environments come from stacking smart choices about how a company uses its assets, balances supply and demand, and builds momentum through mutually reinforcing advantages. These strengths hold up and influence cumulative effect even when market conditions shift.

Take Leicester City’s 2016 Premier League title – a stunning, against-the-odds victory. But it was a one-off. Manchester City, meanwhile, has built a machine combining data-driven recruiting, elite coaching, and financial backing to ensures it stays at the top year after year. Leicester played a brilliant season. Manchester City plays a winning system.

Companies can easily confuse transient advantages (which they can quickly capture but also lose) with enduring ones (which require deeper, long-term investments in assets and capabilities). Constantly chasing trends and transient advantages can easily prevent companies from ever building a sustainable position.

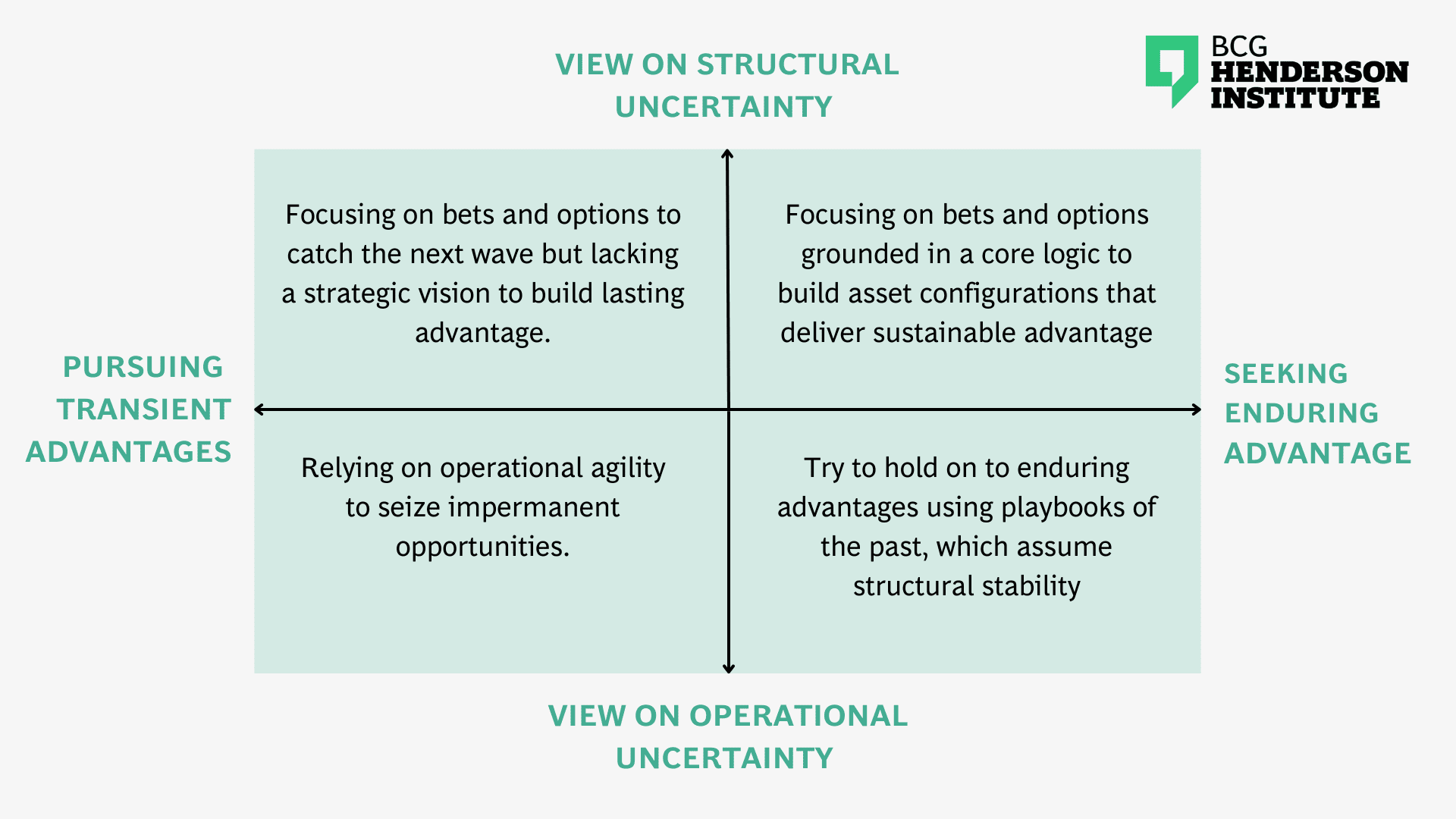

Based on how firms view these two factors, their responses fall into four broad categories:

Some firms may focus exclusively on stability – to the point of operating with playbooks of the past which assumed structural stability – and in doing so fail to adapt to what’s coming. On the other hand, some others may see structural uncertainty and create a continuous stream of adjustments in response, but while lacking a guiding strategic vision to create a path to enduring advantage.

Our traditional view of stability and adaptability as opposing ideas was shaped in a world of structural stability. Enduring advantage of the past was a function of structural stability in industries- which offered scale economies or advantaged positions. Today, firms must adapt to change while simultaneously creating a path to enduring advantage.

Traps that prevent firms from building lasting advantage

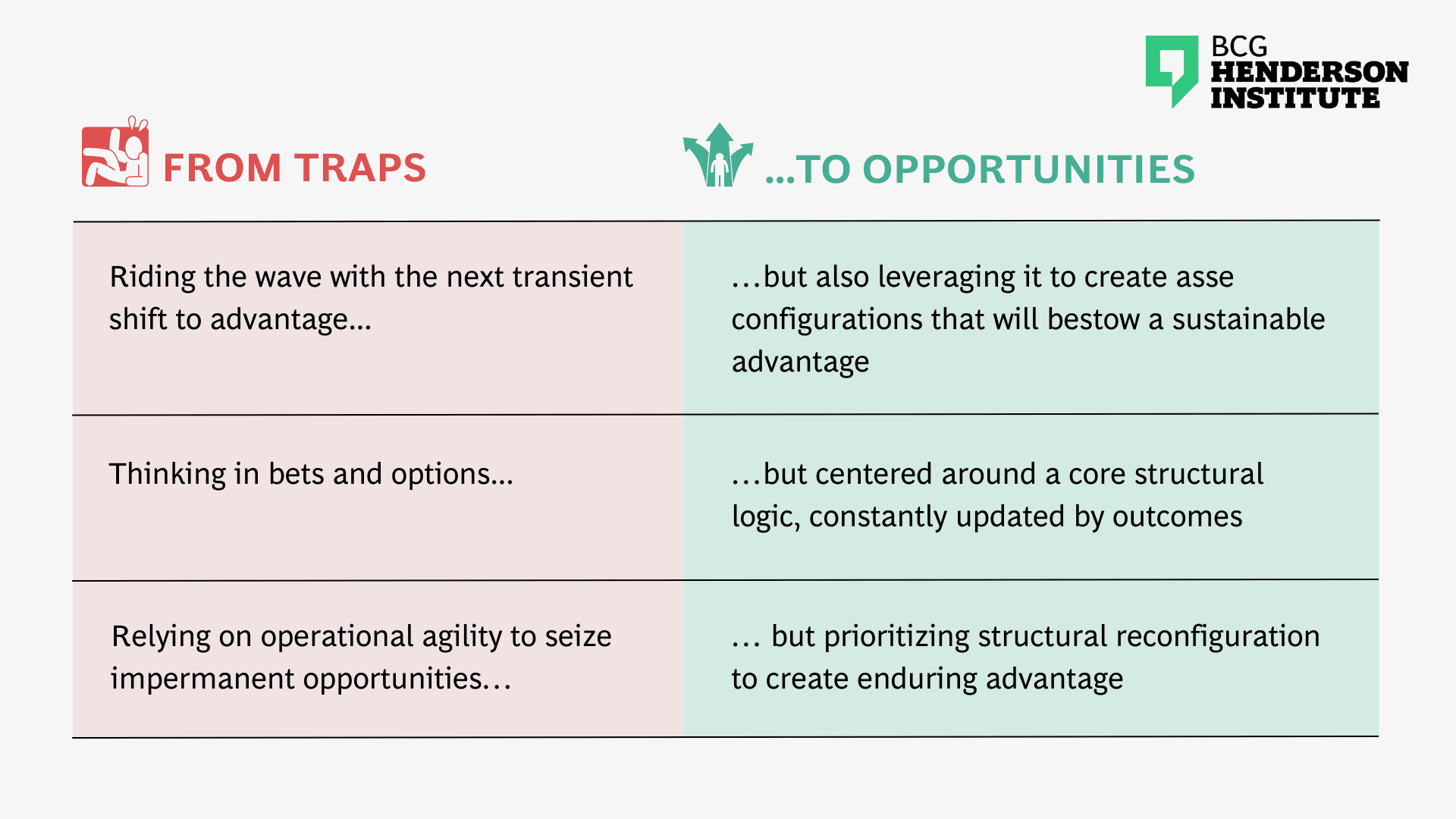

Even firms that recognize the need to adapt while building enduring advantage can fall into several predictable traps, preventing them from building enduring advantages.

Trap #1: Pursue transient advantages alone

A common trap during periods of disruption is the pursuit of transient advantages – fleeting opportunities that promise quick gains but rarely lead to enduring success. It is critical to maintain situational awareness, especially in uncertain times, to avoid blind spots, and stay ahead of disruptions. However, using this awareness only to identify and exploit the next fleeting opportunity is a flawed approach. It positions your strategy on unstable ground, perpetuating a reactive cycle where you’re always chasing the next shift rather than building enduring advantage. Covid-era darlings like Clubhouse and Peloton capitalized on a temporary shift but failed to extend it towards enduring advantage.

Trap #2: Relying on operational agility to address structural shifts

Operational agility keeps us fit but may leave us running the wrong race. It helps us sense and respond faster and capitalize on new opportunities while they last. It also allows organizations to foster a culture of experimentation and curiosity, an imperative when looking to build on success to achieve enduring advantages. But without a clear view of where possibilities for enduring advantage lies, it only leaves us running an endless sense-and-respond hamster wheel.

Yahoo, the original internet-era BigTech, was one of the first major tech companies to implement agile at scale, moving thousands of engineers to Scrum methodology and expanding agile thinking to non-software disciplines like marketing and strategy. Yet, even as it pioneered and mastered operational agility, all these investments failed to address the deep structural shifts underway at that time. Yahoo’s bet on editorial curation of the internet – a manual system that failed to scale in the face of exponential growth of the internet – left it struggling as algorithmic curation with Google’s PageRank and social curation with Facebook’s Like button came in to capitalize on the shift.

Still today, many companies are obsessed with agility – hiring innovation teams, running sprints, and chasing the latest trends. They would do well to learn from Yahoo’s failure. Agile methodologies are operational tools. The trap leaders fall into is assuming these tools will help address the question of where and how to build enduring advantage – they won’t.

Trap #3: Over-reliance on thinking in bets and options

A new conventional wisdom popular among technology businesses suggests that when faced with uncertainty, organizations should embrace options-based thinking by making small bets, focus on doubling down on successful ones, and prioritizing agility of execution to shift the balance of their portfolio of options.

While uncertainty necessitates options-based thinking and bet making, this approach must be grounded in a clear understanding of what drives current and future advantages. Without continuously aligning bets with this structural logic, organizations risk not creating enduring advantage at all or failing to reinforcing it over time. Merely doing something first of fastest, does not necessarily create enduring advantage, and shifting between independent bets does but not compound advantages to may them enduring.

Creating paths to advantage

Companies can adapt while building long-term advantage in several ways. The simplest approach is adjusting surface tactics while preserving core advantages. They can also reinforce existing advantages, develop multiple reinforcing strengths, or create systems that continuously generate new advantages. Ultimately, the most adaptive companies are always searching for fresh sources of advantage.

When change is shallow and infrequent, simple tactics may suffice. When change is frequent and deep, it will be more appropriate to build systems for continuously seeking and implementing reinforcing advantages. In the most radical situations, it may involve a process of searching for entirely new forms of advantage.

In stark contrast to Chegg, consider the online learning app Duolingo, which used the rise of AI to its advantage. Already strong in gamified learning, it used AI to scale personalized education at almost no cost, turning its strength into a self-reinforcing advantage.

Companies that fixate on the binary choice of stability vs change miss the point. What really matters is building a system that compounds advantage over time, by providing a stable internal set of advantages, constantly renewed and reinforced through response to external change. Keep an eye on the environment but also focusing on the system and the advantages it reinforces.

A company must understand its flywheel – the core assets and capabilities that work together for it to win. Every bet should reinforce that momentum. Without a clear flywheel, a company might still place the same bets, but instead of spinning its flywheel, it’s simply spinning or being spun in a hamster wheel, exhausting energy without getting anywhere.

This requires ruthless clarity. What are the fundamental certainties in your industry? What happens if they shift? The companies that endure question the assumptions others take for granted. And they then to adapt towards a new reality while reinforcing their core advantages.

Take BIC in the 1970s. If they had seen themselves only as a pen company, they would have been trapped in a narrowing market. Instead, they asked: “What if we didn’t sell pens?” That question led them to realize their true strength in plastics manufacturing, which opened the door to razors, lighters, and other profitable products. They moved from selling pens to mastering material science.

To build something that lasts in an unpredictable world, you need a new playbook. Spot structural shifts early, use them to reinforce your existing strengths, and find new ones that will outlast the latest shift in external circumstances. Adaptation alone is not enough – it must be purposeful.

Many companies see disruption as an opportunity to cash in – they ride the wave to quick wins and move on. But the smartest ones use such shifts as a chance to rewire or reinforce their business for long-term advantage. They convert temporary spikes in demand into permanent advantages, that outlast the trend. Instead of treating tax breaks and early adopter enthusiasm as temporary tailwinds, Tesla built a global battery supply chain, scaled production, and drove down costs. By the time competitors woke up, Tesla today is more than an automaker; it is an energy company and an AI leader. Similarly, when streaming took off, most media companies rushed to license their libraries. Netflix did the opposite and reinvested in original programming, making itself indispensable even as licensing deals eventually dried up.

Adapt to endure

‘Adapt to endure’ firms leverage advantages offered by a shift in a way that outlasts the shift – this is the key to creating enduring advantage. Firms that do this successfully avoid the traps of transient advantage and capitalize on change and uncertainty to reinforce enduring advantage.

In order to operate, “adapt to endure” firms must repeatedly ask themselves 5 questions

- What are our enduring bases of competitive advantage?

- What are the external changes we must adapt to stay relevant?

- How can we adapt in ways that perpetuate, reinforce, and complement these advantages?

- How can we build managerial systems to repeatedly apply this process?

- And sometimes, how can changes open paths to entirely new forms of advantage?

Change is a playground within which stability is reinforced or created. It’s where we test, fail, and try again until something worth keeping emerges.

The firms that ‘adapt to endure’ thrive. They don’t choose between change and stability; they master both and create a path from one to the other.