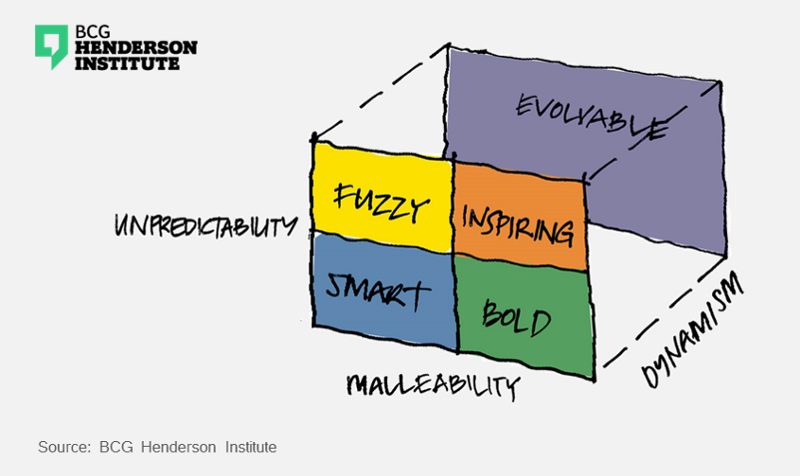

When we try to make a goal useful, we instinctively try to make it more specific. The familiar acronym SMART, coined by George T. Doran in 1981, instructs us that goals should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-based. Financial goals fit well into the SMART framework: for example, Marissa Mayer at Yahoo set out to achieve “double digit annual growth in 5 years”. But the seemingly reasonable idea of having a precise goal may not work when the future is highly dynamic or uncertain. In such contexts, an overly precise goal may be unrealistic and even if it is achieved, what makes sense now may not make sense later.

Setting goals is a key part of business leadership, but we don’t often think about what type of goals may be relevant in each situation — we don’t have a contingent approach to goals. Our research shows that one of the biggest changes in business in recent years is an expansion in the variety of business environments. A key question for business leaders is therefore: What kind of goals are most useful under what circumstances?

Why do we need goals?

Goals fulfill several useful functions in an organization: coordination (to align intentions), abbreviation (to summarize a complex effort), prioritization (to ensure that processes and activities don’t become the main focus), calibration (to tell us how much impact is expected, and indirectly how much resource to allocate or invest), and evaluation (to tell us whether an intermediate outcome is on track).

There are a variety of kinds of goals suited to different circumstances however. The SMART framework can be useful in some contexts but not in others. If we consider a ‘classical’ business environment, which is stable and predictable, it makes sense to set goals that are time-based and oriented around some pre-specified, measurable quantities – because you know the future will largely resemble the past. If there is change, it will be gradual, understandable and within a predictable range, rather than radical and unforeseeable. Such classical environments do exist today: established categories like confectioneries or cosmetics grow with GDP, follow predictable trends and have a stable basis of competitive advantage. Thus Mars Inc. can plan out a multi-year strategy in its core categories, based around well-known consumer trigger points and products that are relatively unchanging. The same applies to predictable routines or processes within the stable, engineered environment of an organization.

Yet in ‘non-classical’ business environments, we need different kinds of goals. Consider so-called ‘adaptive’ environments, which are persistently hard to predict, where advantage is short lived, and where there is ongoing and substantial change. Here, the SMART approach may no longer hold. It’s hard to manage towards success with specific, time-based targets when conditions are dynamic and unpredictable, due to shifting demand, rapidly evolving technology, innovative business models and changing competitive conditions — all characteristic of new or recently disrupted industries.

To help us succeed in non-classical environments, we may need goals to do other things for us, like prompting exploration and new thinking, encouraging improvisation in situations we have never before encountered, or distinguishing between various possible paths forward. Take Steve Jobs’ goal when he rejoined Apple in 1997: “not just to make money but to make great products”, by which he meant making a computer that was “friendly”. This kind of goal wasn’t specific and measurable; his employees had to explore what it meant to create a friendly computer by exploring new paths and testing the results against Jobs’ evolving vision. Rather than focusing the company on a highly specified end — like ‘we aim to lead the market in portable CD players’ — Jobs set a goal that prompted imaginative exploration, ultimately establishing a new basis for competitive advantage.

Why different kinds of goals work in different circumstances

In essence, a ‘goal’ is just a string of words that interact with the human brains involved in a business to produce a useful effect. To see why different goals are effective in different contexts, therefore, it is helpful to look at research on how the brain works, and how this plays out across different environments and situations.

When the environment is predictable, specific goals are possible and useful. We can see why this is true if we look at how the brain works, especially the frontal lobe. When it is possible to do so, the brain breaks down goals into sub-routines, and then compares the outcome of these against the overall goal. In classical environments, then, it makes sense to formulate the goal to leverage this ability: a specific, achievable goal that can be broken down into subroutines.

In contrast, to understand situations in which we face a high degree of uncertainty and novelty, we can turn to a different strand of cognitive science: the brain’s capacity to create analogies. As cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter shows, we make sense of a stream of novelty by drawing parallels with experience we have collected over time — experience which itself has been processed, recombined and reimagined via analogy-making. An analogy is ‘deep’ or ‘rich’ when it suggests similar ‘essential’ structures across apparently divergent situations or ideas.

An example of a goal which draws on this capacity for analogy is Google’s goal statement from 1998: “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”. Rather than being specific, this goal is usefully fuzzy, prompting us to draw analogies. And indeed the goal achieved this effect. In a meeting in 2004, founder Sergey Brin introduced his leadership team the company Keyhole, which was making satellite maps of the world. At first the executives enjoyed playing with the software, zooming in on their own houses, but it was the company’s overarching goal which helped them to see this as a legitimate and logical business opportunity. The SVP of engineering Wayne Rosing observed: “if our mission is to make all the world’s information useful and accessible — then this is the real world”. The overarching goal helped the executives draw an imaginative link from search to maps, as two aspects of the same effort, organizing the world’s information. Such a goal opens a field of thought, prompting us to explore by looking for a common essence in different places. In this case the journey was successful: Google Maps now has over a billion users. A more specific goal — for instance ‘create a search engine used by half the world’s people by such and such a date’ — does not open the path to Google Maps; on the contrary, it suggests that creating maps is an irrelevance, not even worth exploring. Thus the wrong kind of goal can risk shutting down the exploration that is necessary to navigate unpredictable environments. The less predictable the environment, the more we should consider creating fuzzy goals, rather than always aiming for maximum specificity.

Varying malleability

Another dimension along which business contexts can vary is malleability, or the extent to which a company can actively shape its environment. As malleability increases, the scope of goals should be more ambitious and externally oriented. This makes intuitive sense but is not always obvious in practice. For example, we may not think of Zara as a modest company, but modesty is in fact central to its goal setting, which has enabled it to generate extraordinary market and financial success. Zara is aware of what it cannot change — fashion trends — and instead aims to be a fast responder to current preferences. This approach is captured in its goal of “satisfying the desires of our customers”. While this goal may not sound modest, its restraint is evident when compared with the goals of competitors, for instance: “To become the company that defines global modern luxury” (Coach), or “To be the Ultimate House of Luxury, defining style and creating desire, now and forever” (Chanel).

In less malleable environments, goals conflict with a persistent cognitive bias: illusory superiority. This bias concerns our tendency to overestimate what is within our capacity to change. Goals often need to limit our ambition, or focus attention and effort on tasks that are actually within the company’s realm of influence. This principle is clear in the case of small businesses: a family-run shoemaker in Florence aims to “make special shoes for a special few”. A larger scope than this might sound good, but would likely be unrealistic. Larger companies can also delude themselves about their degree of control.

In more malleable environments or situations the scope of goals can conversely be more ambitious. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy set a bold goal for NASA: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth”. This was a specific and time-based aim, but with an ambitious scope, which turned out to be warranted. Compare this to NASA’s goal as stated by its administrator Charles F. Bolden in 2014: to “expand the frontiers of knowledge, capability, and opportunity in space”. This goal has an equally ambitious scope, but it is usefully fuzzy: it does not set out a specific action or end point, but inspires us to ask what is possible in space, standing on the frontier looking (and thinking) into the unknown. It leads us to both explore and shape the broader environment, to collaborate with actors beyond the organization connected with the future of space.

When the malleability of the environment warrants an ambitious goal, it should be designed with a different cognitive bias in mind: the status quo bias. This bias inclines us to believe that the costs of change are higher than they actually are, causing us to sacrifice potential value. Ambitious goals are effective to the extent they overcome this bias, by making vivid in people’s minds the attractive aspects of bold change.

Ambitious goals also frequently involve enlisting the support of customers, suppliers, investors and other stakeholders. They should thus also be formulated to articulate the common good that might be attained, appealing to the interests and desires of a broad and diverse set of minds.

To summarize, SMART goals are sometimes smart and sometimes not. A more effective way to think about goals is a contingent approach: the more unpredictable the environment, the more we should consider making goals usefully ‘fuzzy’, allowing the brain to draw on analogies; the more malleable the environment, the more we should consider an ambitious scope and an external orientation.

The intelligent evolution of goals

Another common belief about goals is that they should change only infrequently. ‘Moving the goalposts’ is a metaphor for cheating. But a contingent approach to goals also involves recognizing that goals may need to evolve over time. There can be three triggers for this:

- We move from one kind of environment to another: If the business environment shifts over time, say from a more to a less predictable context, we should consider changing our goals, in this case from specific to usefully fuzzy.

- Our company changes: Major developments in what our business is able to accomplish, due to capability development or mergers and acquisitions, should also trigger a re-articulation of overall goals.

- We learn more about what it is we were pursuing: In our personal lives, we may seek out something enthusiastically (for example, higher status), but when we attain it, we may realize that was not actually what we wanted (we may have actually wanted to be appreciated by others, for instance, which we later realize does not result from achieving the former). That is, experience leads to greater insight, which can change our goals.

For business, this occurs in those moments when leaders say: ‘we realized we were actually in the business of X’, or ‘we realized this is what we were actually trying to do’. For example, McDonalds initially considered itself in the restaurant business, but owner Ray Kroc realized that it was actually in the real estate business. On realizing this, it would make sense for the management of McDonalds, or any company in an equivalent situation, to update their shared goal.

Alibaba is one company which has evolved its goals, through a combination of all these triggers. In the late 1990s its initial goal was to be “an e-commerce company serving China’s small exporting companies”. But as the market changed in the early 2000s — Chinese domestic consumption exploded — the company expanded the scope to “the development of an e-commerce ecosystem in China”. Then recently, in response to the convergence of physical and digital channels, the company changed its goal again to: “We aim to build the future infrastructure of commerce”. This last evolution appears to be spurred by a combination of a changing environment, a changing company, and a more insightful articulation of the path the company had been on implicitly all along. Building “the future infrastructure of commerce” is a usefully fuzzy proposition, leading us to imagine what new forms commerce might take in future. And the scope is ambitious, aligned with the massively expanded capacity of Alibaba to shape its environment. Alibaba is quite explicit about the need to evolve its goals, believing that everything in the company, including its vision and goals, should evolve to match changing realities.

The takeaway point is that goals are not just contingent on the current environment, but should also change over time. Of course we can always just stick to our goals despite major shifts, but being ready to evolve them can sometimes open up more fruitful paths.

Having no goal

Does it ever make sense not to have a goal? We have seen that goals are tools which get useful jobs done in different situations. There is at least one type of situation where a useful job gets done by avoiding setting goals. This is when we want to allow ourselves to play or dream. Unconstrained dreaming or exploration is an important way of simulating, exploring and learning, without the negative consequences of risk taking in the real world. It exploits the unique human capacity to simulate experience mentally before taking action.

Unstructured playfulness is key to creativity. In playing we allow ourselves to challenge structures, rather than be guided within them. The artist M.C. Escher is an iconic example of this; his drawings show a world where unquestioned constraints have been thrown up in the air, and put together in different ways. He wrote: “I can’t keep from fooling around with our irrefutable certainties. It is, for example, a pleasure knowingly to mix up two- and three-dimensionalities, flat and spatial, and to make fun of gravity.” ‘Making fun of gravity’ is what we sometimes need to do in business, as we let ourselves forget conventional wisdom and imagine unusual combinations of ideas, images, hopes, and situations — a journey to distant mental spaces from which we might bring back valuable new thoughts. This is especially so in a world where technological and social change are undermining old certainties and precipitating new ways of doing and thinking. In fast changing environments, companies are effectively competing on imagination, and an overly structured approach and goals can inhibit this.

Unstructured thinking occurs in the brain as daydreaming, which is accompanied by distinct patterns of neural activity. Though our knowledge is still at an early stage, we know that this involves different, normally unconnected, regions of the brain being activated simultaneously. It is thought that creativity is heightened in such states because the brain stumbles on interesting “novel orderly relationships”. We mostly set goals so that processes don’t become the point, but sometimes we want the journey, or the process, to be the point — to venture far away from business-like instrumentalism, in order to come back to eventually formulate new, more imaginative goals.

Harnessing the power of contingent goal setting

We conclude by adopting the usefully fuzzy goal of giving some broad hints to leaders on how to apply and exploit the discipline of contingent goal setting

- Identify the environment you are in and ask if the type of goals you have are suited to the situation. You might then consider changing the scope or specificity of those goals

- To make a usefully fuzzy goal, use terms which are rich in possible analogies, but not yet fully specified, to drive exploration. Use the following steps as a guide:

-

- Consider the generality, or ‘essence’ of what your business is trying to accomplish, or organizational strength you are playing to

- Identify where else this applies in business and life — drawing on your personal and professional experience

- Formulate a goal based on this essential idea — the common thread which can connect multiple analogous experiences

- Reflect on where your organization has come from and how its understanding of its goals has changed — to see the pattern of evolution so far and note any tension between this trajectory and your current goals. For example, Google is now considering organizing the transport system, and its leadership is reportedly questioning whether it has now outgrown its original goal statement.

- Regularly ask yourself these fundamental questions about your business, and use them to drive the evolution of your goal

New situations require new thinking, including reconsidering some unquestioned tenets of business. By adopting a contingent approach to goal setting companies can better equip themselves to adapt to today’s fast- changing business reality.