By Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak and Paul Swartz

Evidence of price increases (CPI) as well as news of labor and product shortages have further escalated inflation fears over the last week. Many clients and readers have asked if this changes our view of inflation’s likely path. It does not, and in this report we lay out what it would take to change our view, along with nine data points that we like to watch in this regard.

We continue to see current price spikes as by-products of a unique shock. Following last year’s sudden stop, which spawned widespread concern about deflation, we now witness an unprecedented acceleration. This symmetry feeds through to idiosyncratic price gyrations which do not currently add up to systemic pressures.

Specifically, we would worry about changes in three dimensions:

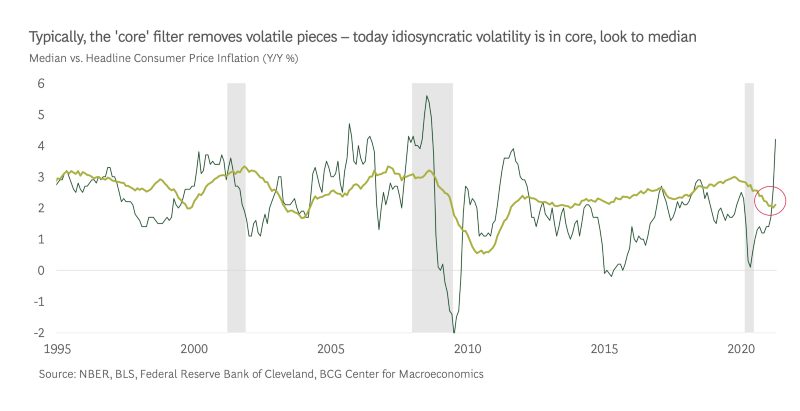

(1) The breadth of inflation. Though “core” inflation has posted strong month-on-month growth (not just year-on-year which is largely driven by baseeffects), sustained inflation requires a broad-based rise in consumer prices. Yet, median inflation, a reliable gauge of broad-based price change, has not moved. Meanwhile, the rise in the core CPI index can be largely ascribed to two unusual effects, product shortages and normalization from abnormally low price troughs. Neither looks systemic or sustainable over the medium term.

(2) Inflation expectations. The popular focus on rising inflation compensation, such as 5Y5Y market data, can be misleading. Inflation expectations are only one piece of inflation compensation and it’s mostly the other two pieces — inflation risk premium and liquidity premium — that have driven up 5Y5Y inflation compensation. Specifically, the shrinking supply of real bonds (TIPS) has pushed up the liquidity premium.

(3) Economic potential. It’s easy to forget that low inflation was consistent with an economy operating at and above potential pre-Covid. Hence evidence of lower economic potential would worry us, such as the failure of the participation rate to normalize. But older and younger cohorts have already returned meaningfully. Middle-aged cohorts have not, and their participation is a critical variable to watch in the fall when schools fully re-open and vaccines have percolated more completely.

We also re-iterate the difference between cyclical and structural inflation risk. Policy makers have placed a bet that could go wrong and would result in cyclical inflation. For this to turn into a structural inflation regime break, policy makers would have to double down on a losing bet and keep pushing fiscal and monetary policy. While that remains a part of the risk distribution, a far more likely outcome would be monetary tightening that delivers a recession and thereby puts a cap on cyclical price pressures.

Read more here.

About the authors

Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak is a partner and managing director in BCG’s New York office and global chief economist of BCG. He can be reached at Carlsson-Szlezak.Philipp@bcg.com

Paul Swartz is a director and senior economist in the BCG Henderson Institute, based in BCG’s New York office. He can be reached at Swartz.Paul@bcg.com