To succeed in the next decade, leaders will have to fundamentally reinvent their organizations as hybrid learning enterprises that synergistically combine humans and technology. But getting from today’s current state to the necessary future state will be a challenging journey.

Many businesses have deeply entrenched operating systems that are predicated on hierarchy and human decision-making. They will need to redesign their internal processes and build new capabilities and business models — in other words, to undergo deep transformation. Furthermore, this will not be a one-time change effort: the dynamic nature of business will require organizations to build ongoing capabilities for large-scale change to keep up with evolving technology and competition.

Traditional approaches to enacting organizational change are generally not very effective, however. Change management is generally thought of as “one-size-fits-all” and based on plausible rules of thumb. But our research shows that only about one in four transformations succeeds in the short and long run, and the success rate has been trending downward. Meanwhile, the stakes are extremely high: the difference between success and failure for the largest transformations can add up to the company’s entire market value over a decade.

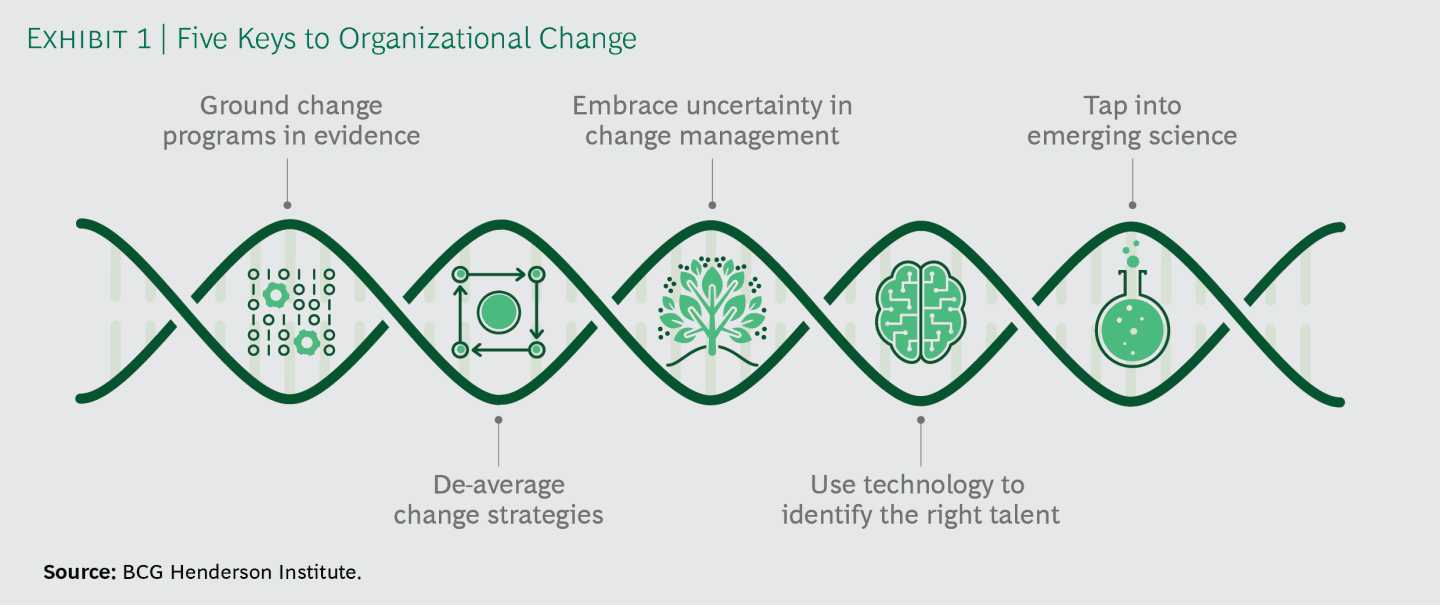

Leaders need to take a new approach to change — one that deploys evidence, analytics, and emerging technology. In other words, leaders must apply the emerging science of organizational change, based on five key components. (See Exhibit 1.)

- Ground change programs in evidence.

- De-average change strategies according to the nature of the challenge at hand.

- Embrace uncertainty and complexity in change management.

- Use technology to identify the right talent to execute change.

- Tap into emerging science to enhance change programs.

Ground change strategies in evidence

When it comes to understanding how to enact change, many business leaders traditionally rely on intuition and experiential rules of thumb. In a typical transformation effort, the program design, choice of tactics and value levers, and ongoing management are often based on little more than subjective data such as customer surveys and progress reports. But the increasing availability of data, together with novel analytical approaches, has made it possible to empirically decode what really works and what doesn’t. We call this approach “evidence-based transformation.”

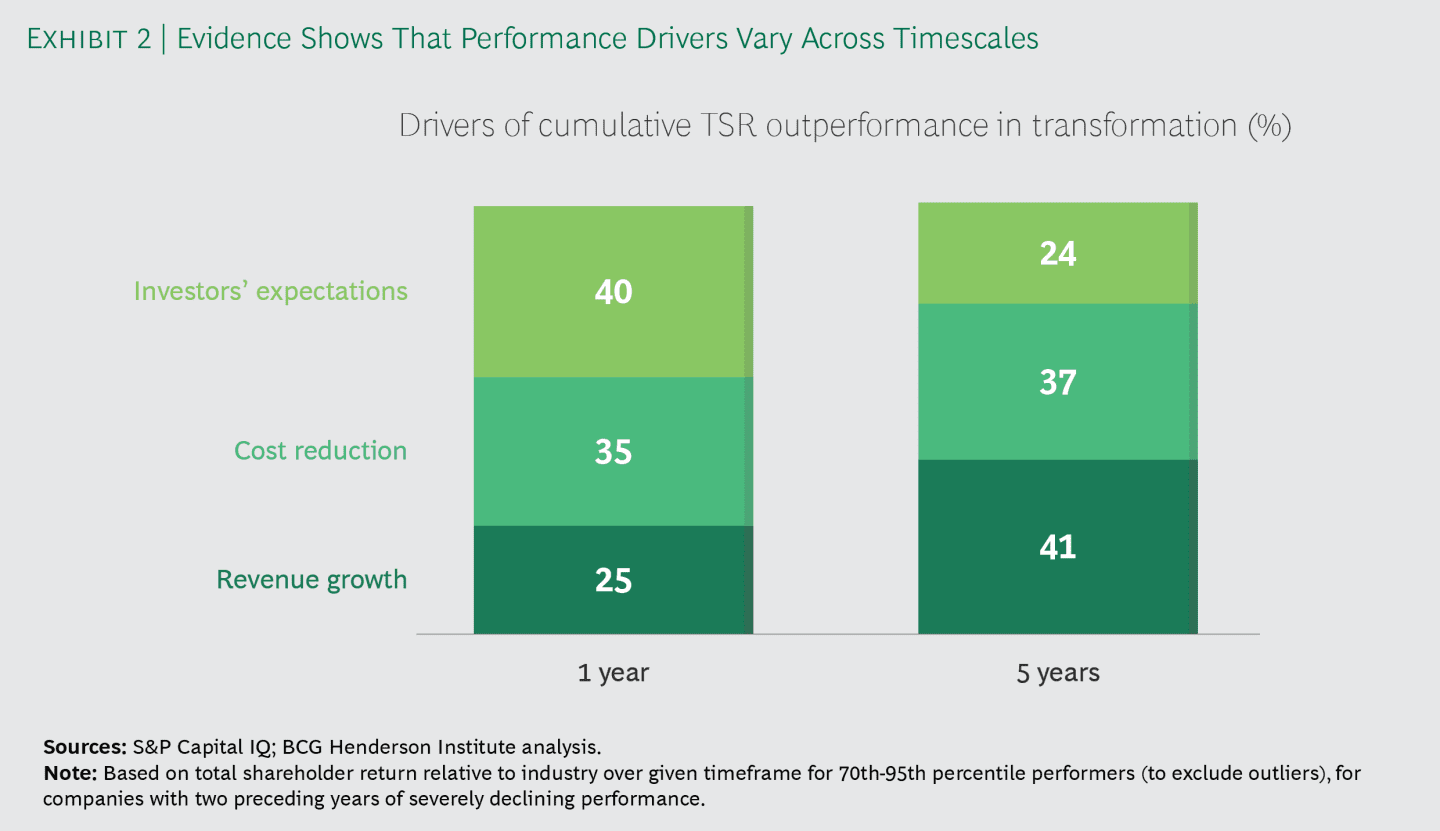

Our empirical analysis of hundreds of large companies that experienced major change reveals a number of lessons. In the short term, the most successful companies articulated a compelling story to reset investor expectations in addition to improving efficiency. (See Exhibit 2.) In the longer term, they took actions to increase revenue growth, such as spending more on R&D. Throughout the effort, companies that formalized their transformation programs and invested in them were more successful. Finally, transformations initiated preemptively, rather than reactively, led to better performance.

To succeed in the next decade, leaders can apply such an evidence-based approach to all types of change situations — turning transformation from a reactive necessity into a competitive opportunity. For example, empirical analysis can help companies successfully acquire and transform underperforming businesses: our research shows that although such “turnaround M&A” deals are very risky, there are demonstrable ways to beat the odds.[1]“Beating the Odds in M&A-Based Turnarounds” (forthcoming) These include launching change indicatives quickly and setting ambitious synergy goals, as well as giving attention to key “soft factors” — for example, companies with a well-defined purpose had significantly better outcomes in turnaround deals, demonstrating the importance of motivating employees on the change journey.

A similar approach can also help companies respond to changing external conditions, such as an economic slowdown: while most companies see performance decline during a downturn, a minority thrive — and historical analysis can identify what sets them apart.

What steps can leaders take to learn from an evidence-based transformation approach?

- Draw insights from the full range of historical evidence, rather than relying only on personal experience or rules of thumb.

- Build analytical capabilities to be able to identify tailored insights for your individual change situation and optimize program design accordingly.

- Create a sense of urgency in your organization to make the case for preemptive change.

De-average change strategies

Organizational change is often seen as a single type of challenge — where one form of change management is sufficient for all situations. Accordingly, most change efforts follow one recipe with common ingredients: for example, centralized program offices, periodic pulse checks, measurement against predefined milestones, and a one-shot process with a clear end date.

In reality, there are many types of organizational change that have very different challenges and requirements. Leaders need to de-average organizational transformation into different components and understand the right approach for each.

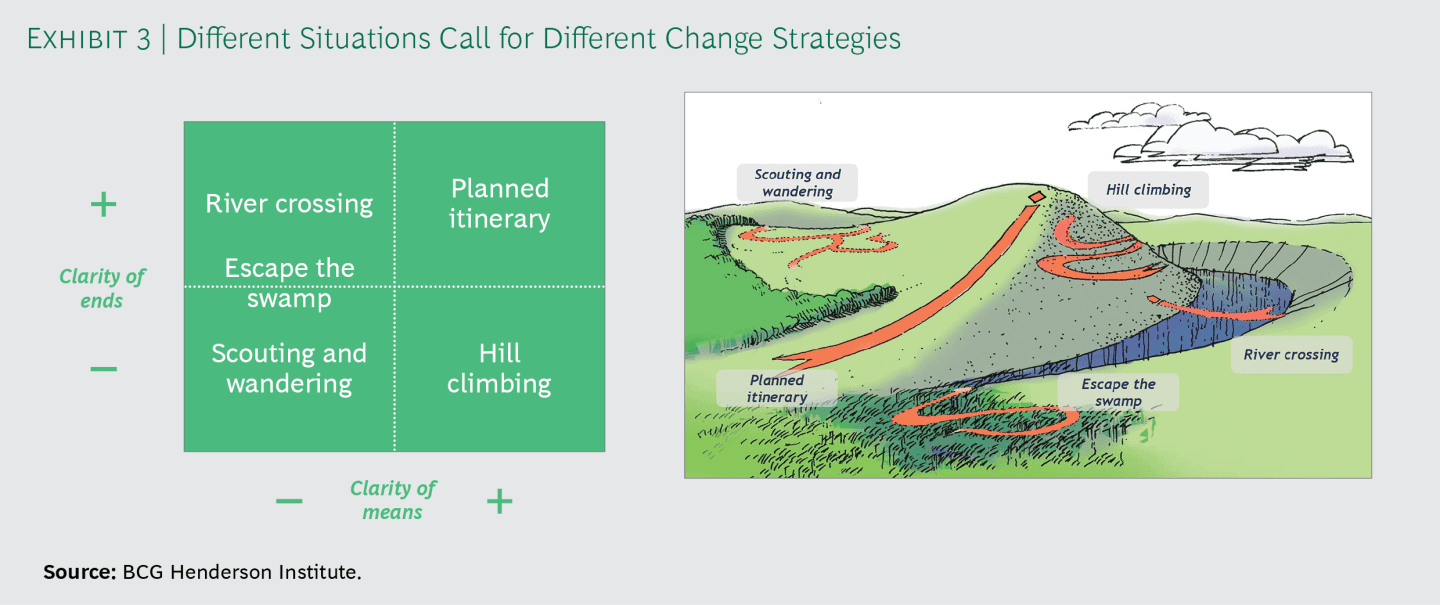

Change can be considered as movement across a “landscape” of possibility, where each point corresponds to a different possible state of the organization. Organizations try to seek “higher ground,” which corresponds to higher potential performance. Different change situations can be considered along two dimensions: Is the target destination clear (the ends)? And is there a clear path to get from here to there (the means)? (See Exhibit 3.)

De-averaging the challenge this way reveals five types of change strategies, each of which requires a fundamentally different approach to change management:

- A planned itinerary represents the traditional approach to organizational change. This is appropriate when there is a clear goal for how the organization can be improved, and there are obvious steps to get there. For example, HSBC identified a clear opportunity to simplify and streamline its business, through the well-defined means of exiting non-core geographies and eliminating excess organizational layers. It executed the program with a typical goal-oriented approach, setting clear cost and profit targets, reporting its progress against those targets, and clearly defining accountability.

- A river crossing strategy is more appropriate when there is a clear end goal but the path to get there is unknown.[2]As coined by Deng Xiaoping, who described China’s reform effort as “crossing the river by feeling for the stones.” For example, Starbucks in 2008 understood it needed to increase customer loyalty, but didn’t know precisely how to do so. Rather than planning its change program in detail, it took a more experimental approach to find the best path — running pilot programs in emerging areas like social media, learning from those efforts, and amplifying the actions that made concrete progress toward its goal.[3]“Starbucks Coffee Company: Transformation and Renewal” (HBS, 2014)

- A hill-climbing strategy is needed when the means of change are clear but the end state is not. For example, John Deere has taken an open-ended approach to its investments in Internet of Things technology: rather than defining an end goal from the beginning, it started with a few minimum viable products that were believed to be heading in the right direction. After learning more about the value of those products, the company aims to “build from those and create a broader service around them” — eventually reaching an end state that likely could not have been foreseen.[4]“John Deere is plowing IoT into its farm equipment” (Network World, 2016)

- Companies may seek change even when they know neither the ends nor the means — for instance, when they are looking for the next big exploratory opportunity. This situation calls for a strategy of scouting and wandering. For example, the Japanese company Recruit instituted an exploratory program called Ring, which allows any employee to propose starting a new business — not only those related to the company’s existing products, but in “any and all business fields.” The program receives more 1,000 new ideas every year, some of which were ultimately adopted by Recruit and became substantial businesses.

- Finally, some companies face situations in which the only clear imperative is that they need to change substantially and urgently, which demands an escape the swamp strategy. For example, facing severe threats in 2012, Best Buy adopted a philosophy of, “If we don’t change, we are going to die.” [5]“Best Buy Should Be Dead, But It’s Thriving in the Age of Amazon” (Bloomberg Businessweek, 2018) In other words, the company pursued bold, pragmatic moves without exhaustive evaluation, because they represented its best chance to promptly escape an adverse situation.

Major transformation programs, such as the ones many companies will have to undergo to reinvent themselves for the next decade, require a composite of these strategies — in which various change management approaches are applied in sequence, or in different parts of the business simultaneously. Companies therefore need to develop capabilities to tackle each type of change effectively.

A few key imperatives can help leaders leverage the required variety of change strategies:

- Understand the variety of potential change challenges and the tactics required to succeed in each.

- Divide complex transformation efforts into their different components, and select change strategies accordingly.

- Build organizational and leadership capabilities to enact multiple types of change simultaneously.

Embrace uncertainty and complexity in change management

Businesses have been traditionally managed with a “mechanical” mindset. This mentality assumes that everything that needs to be known can be known, everything that needs to happen can be planned, and all necessary change can be enacted through direct intervention.

However, companies are composed of people who interact with each other and with a complex dynamic environment. So businesses, like other biological systems, behave like nested complex adaptive systems. Lower-level systems (such as individuals) are embedded in higher-level systems (such as teams, business units, companies, industries, national economies, and societies) — and changes in any one part of the system can cause unintended and unpredictable effects in others.

Interactions between individuals or systems are becoming even more complex today, because employees, companies, and economies are more connected as a result of digitization, and because production is starting to be organized in dynamic multi-company ecosystems rather than traditional static supply chains. Therefore, mechanical approaches to change management are increasingly inadequate. Instead, leaders need to employ a more “biological” approach to change — which is more realistic about what can be known and directly controlled.

Biological management involves several different principles:

- Adapt to changing conditions by seeing what works, rather than designing or deducing static solutions.

- Shape the organizational context, rather than dictating individual actions.

- Allow new approaches to emerge from a diversity of perspectives, rather than relying on standardization.

- Observe how the organization behaves as a whole, rather than optimizing individual parts.

- Compete on resilience and preparedness for the unknown, rather than only static efficiency.

These principles point to new strategies for enacting change in business. To address a complex task (for instance, shifting a company’s culture), direct interventions (such as mandating individual behaviors) are unlikely to bring about the required change. Indirect interventions — those that change the mindset, assumptions, and context that underpin employees’ actions — often prove to be more effective because they touch the deeper, more persistent drivers of behavior.

Biological approaches also enable the orchestration of external change, such as shaping the behavior of other players in a business ecosystem. For example, early in the evolution of its Taobao e-commerce platform, Alibaba wanted to expand the range offerings by making it easier for small or inexperienced sellers to join the market. Rather than addressing this challenge through direct actions, the company instead set up “Taobao University” — a platform on which established sellers could produce certified training materials for new sellers to learn from. By finding this indirect leverage point, Alibaba was able to capture the best wisdom from its marketplace, transmit it to potential sellers with greater scale and specificity, and improve the quality of services on Taobao, which ultimately became the world’s largest e-commerce website.

What steps can leaders take to embed biological thinking in change management?

- Be realistic about what you can predict and what is beyond managerial control.

- Foster trust and reciprocity to coordinate competing interests.

- Experiment frequently and amplify initiatives and approaches that are most successful.

Use technology to identify the right talent to execute change

Large-scale organizational change often results in a need for new capabilities, which may be found by reallocating workers to different positions within the enterprise or by identifying new talent externally. In order to execute change effectively, it is therefore necessary to develop strategies for identifying individuals’ unique skills and matching them to roles in the target organization.

The challenge of aligning skills with positions, like many other aspects of large-scale change, has been generally based on subjective judgements around individuals’ track record of performance in different roles. But advances in science and technology are unlocking new possibilities. The study of neuroscience, and advances in testing technology, allow for the rapid, scalable identification of cognitive and emotional traits — which are more objective than self-reported survey measures or judgements based on interviews. And AI can now find and refine complex relationships between these traits and job performance across very large sets of traits and roles.

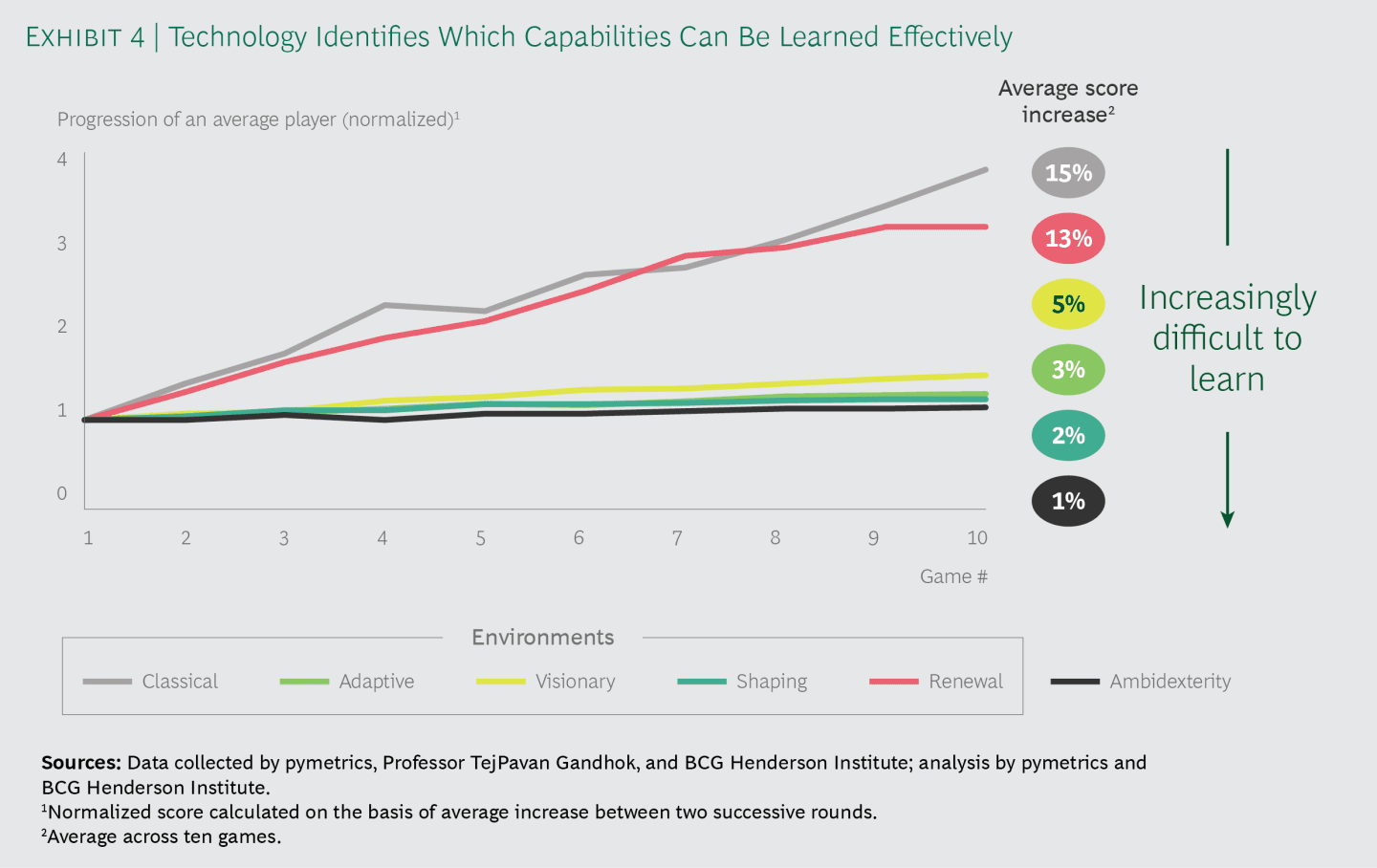

For example, our research (in collaboration with pymetrics, a startup using neuroscience and AI to help companies improve hiring processes, and Professor TejPavan Gandhok of the Indian School of Business) used digital games to assess individuals’ cognitive and emotional traits as well as their skills in different simulated problem-solving environments. We found that different neuro-traits reliably predicted success in different situations, suggesting that science can indeed play a helpful role in identifying talent to fill new roles. And we found that very few individuals were successful in all environments — demonstrating the need to effectively align skills with roles.

Furthermore, there were clear differences in how well different capabilities could be learned over time. Some capabilities could be learned effectively, indicating that businesses are able to develop them internally over time — while others could only be learned very slowly, indicating a need to acquire them externally if they cannot be found within the organization. (See Exhibit 4.)

How can leaders ensure they have the proper capabilities to successfully execute change programs?

- Use objective measurements of individuals’ skills, and de-average talent needs in different parts of the business.

- Make hire-or-build decisions based on the learnability and market for different capabilities.

- Maintain a diversity of skills throughout the organization for when new challenges arise.

Tap into emerging science to enhance change

As science and technology advance, more tools for managing change in complex dynamic environments will emerge. The leaders who are willing to let go of established models and embrace this frontier will have an advantage in transforming their organizations in the next decade.

Some emerging lessons from science and technology include:

- Identify early warning indicators. Understanding when and how change is required is no easy task. By the time traditional performance measures signal a need for change, it is often too late to recover. In some domains, however, scientific study has revealed “early warning signals” — higher-order patterns that predict critical changes to complex systems in advance. For example, in ecology, certain configurations of vegetation in dry regions are indicators that the region is about to become completely barren.[6]Scheffer et al., “Early-warning signals for critical transitions” (Nature, 2009)

Businesses may be able to identify early warning signals of impending shifts — for instance, the threat that their current growth engines will run out of steam — and understand how to change accordingly. For example, Thornton Tomasetti, a leading engineering firm, has adopted new metrics to measure its vitality to identify warning signs of deterioration before they show up in measures of financial performance.

- Learn how to “nudge” behavior effectively. As business leaders shift from mechanical approaches to indirect ones that account for uncertainty and complexity, they will need to identify influential leverage points in the business that may not be obvious. The emerging study of behavioral psychology can help leaders identify small interventions that may nudge employees into different, more productive behaviors. For example, in a randomized experiment Virgin Atlantic found that giving reminders and fuel use goals to pilots resulted in millions of dollars of cost savings.[7]Gosnell et al., “A new approach to an age-old problem: solving externalities by incenting workers directly” (NBER, 2016)

- Leverage new program management technologies. As companies adopt an expanded array of change strategies, they will need new methods of reporting on and managing those programs. Emerging technologies may be able to help. For example, new digital crowdsourcing platforms may offer a template for companies to gamify change initiatives and gather real-time feedback about what works and what doesn’t. And dynamic program management platforms can enable leaders to continuously adjust the portfolio of change initiatives instead of following unchanging timelines.

- Use AI to enhance change. Lots of organizations are enacting major change so that they can use artificial intelligence effectively (often called “digital transformation”). But few are using the capabilities of AI itself to enhance major change programs themselves. Instead, change efforts are still largely designed and managed with subjective approaches.

However, in the next decade, forward-looking companies will likely leverage increasingly powerful AI capabilities as an essential part of their change programs. For example, machine learning has already shown remarkable ability to predict the dynamics of some chaotic systems, such as weather.[8]“Machine Learning’s ‘Amazing’ Ability to Predict Chaos” (Quanta Magazine, 2018) Similar technologies could identify disruptions in the business environment or diagnose organizational health in real time.

For example, according to analytics startup KeenCorp, deep semantic patterns in Enron’s internal emails identified latent tensions in the organization, which could have served as a sign of trouble to observers even if they did not know the full extent of its fraud.[9]“What Your Boss Could Learn by Reading the Whole Company’s Emails” (The Atlantic, 2018) This type of analysis could be applied not only to legal risks, but to strategic risks as well.

How can leaders use the emerging science of change to their advantage?

- Identify the new metrics and analytical approaches that can provide early warning signals to your specific business.

- Use AI to optimize and enhance the change process itself.

- Monitor ongoing technological and scientific advances to identify new opportunities, perhaps including generative AI algorithms, biometrics, or control theory.

Major, ongoing change will be necessary to succeed in the next decade. But successfully enacting organizational change is highly challenging. By recognizing the complexity of change, and using lessons from science and analytics to address it, leaders can ensure their companies are best-positioned to win the ’20s.