When Greek astronomer Hipparchus invented the arithmetic mean, he created a lastingly useful mathematical tool for summarizing distributions of different values. But in contrast to macroeconomics, strategy has never been about averages. Strategy is about defying the powerful forces of commoditization and reversion to the mean by being exceptional in some way.

The need to think about the world in de-averaged terms and avoid becoming average oneself has never been truer than it is today. It’s therefore a good time for leaders to remind themselves of the necessity and art of defying averages.

Strategy has never been about averages

Over time markets are commoditized: new competitors appear, standard product designs emerge making offerings more comparable, and consumers then enjoy more choices and become better educated in exercising those choices, forcing down prices to marginal cost and returns to the cost of capital.

Traditionally, one way to be advantaged in such a situation is to be exceptional through scale and costs. In 1968, Bruce Henderson proposed the experience curve, explaining how early entrants can accumulate volume and experience faster, thereby becoming the lowest-cost players in their industries. In 1976, Henderson observed that when equilibrium has been achieved in unregulated markets, they can support no more than 3 profitable significant competitors, which tend to have market shares in the proportions 4:2:1. This remarkable observation has been since validated by extensive analysis across all industries.

The other traditional route to avoiding average returns is to be exceptional through differentiation, by creating new products and markets and playing in spaces with structurally low competitive intensity because of barriers to entry. Combining these two ideas, Michael Porter proposed in 1980 that companies could be competitively advantaged only through cost leadership or differentiation.

As the pace of business accelerated due to global competition and (primarily Japanese) managerial innovation in the 1980s, it became apparent that structural advantage was only temporary, and the idea of being exceptional through speed came to the fore. In 1990, George Stalk and Thomas Hout proposed time-based competition: by having fast, uncluttered end-to-end business processes, companies could be first to market and also enjoy higher quality and lower costs, and thus achieve above-average returns.

And as the pace of competition accelerated further, driven mainly by unprecedented innovation in digital technology starting in the 1990s, the notion of serial temporary advantage — for example, in adaptive advantage and the self-tuning enterprise — was proposed as a new basis of competition, one that is focused on learning and adapting faster than competitors to changing environments.

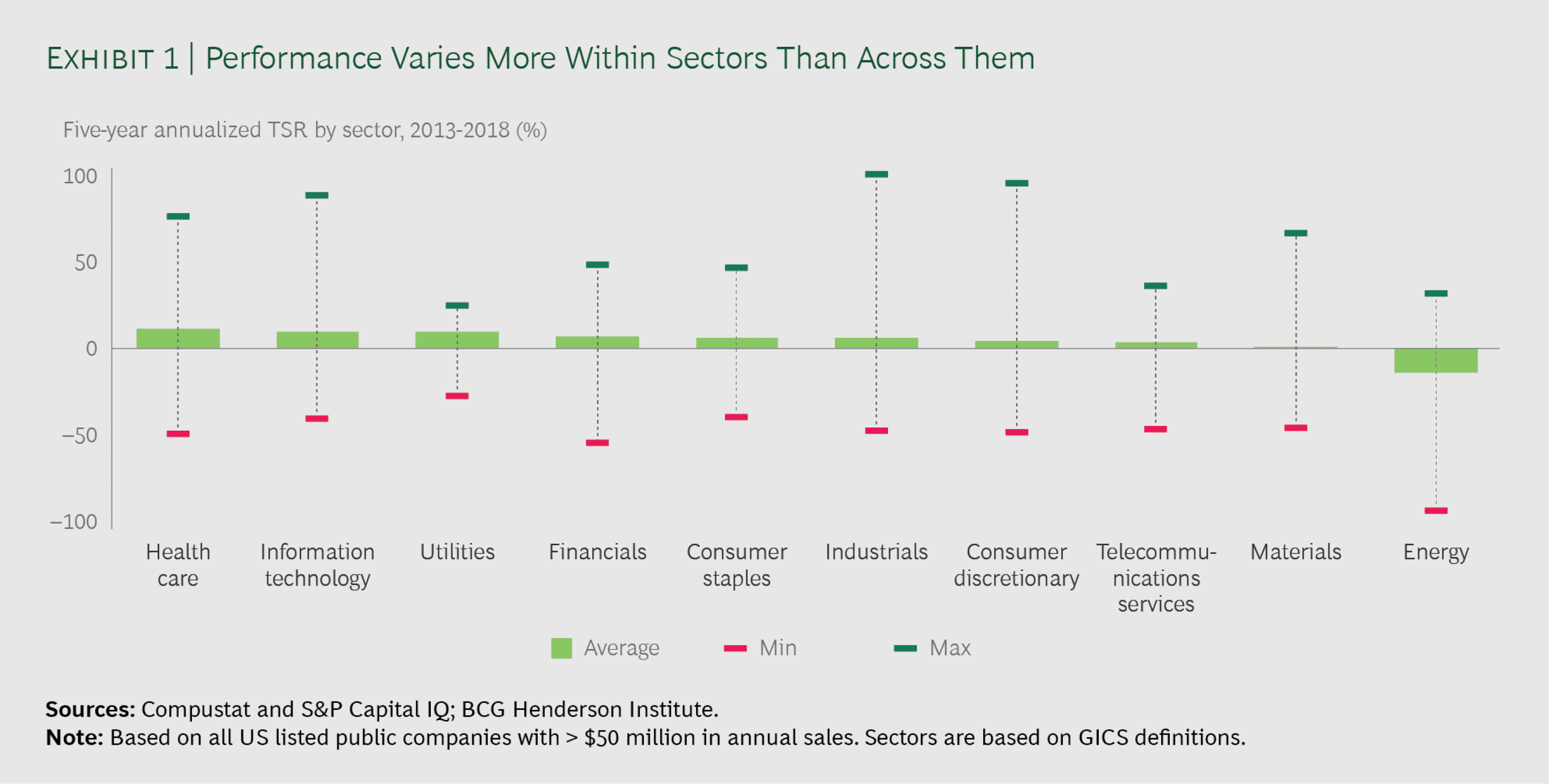

Business strategy has thus always been about avoiding average returns by being exceptional with respect to scale, differentiation, speed or capabilities. While some industries are significantly more attractive than others, the spread of performance within industries is an order of magnitude greater than that across industries. How to play (being exceptional compared to your peers) therefore matters much more than where to play, and there is really no such thing as a bad industry [Exhibit 1].

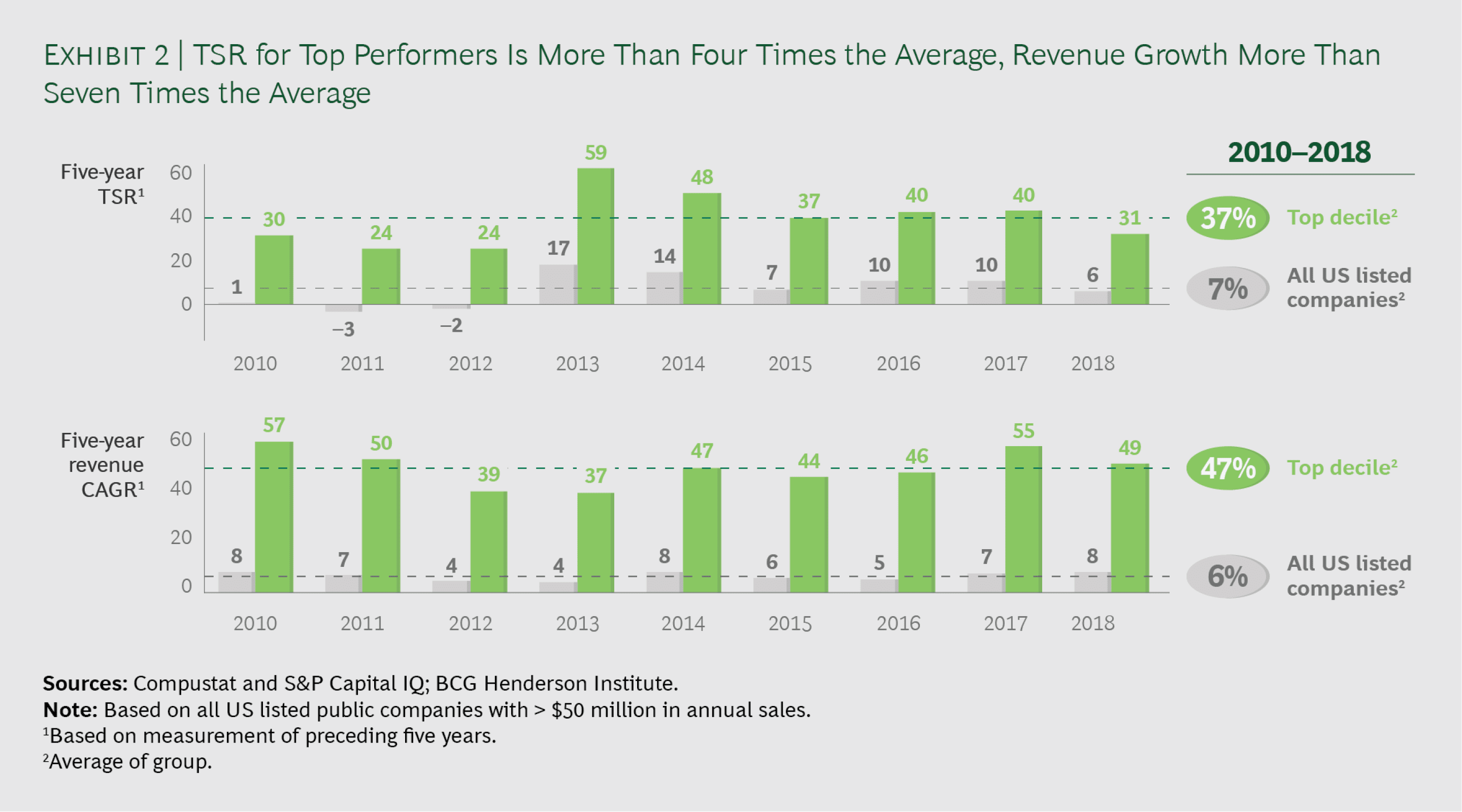

In fact, the spread of company performance is skewed and long-tailed, meaning that the value of being exceptional can be huge.

- On average, large companies generate annual TSR of 7%, but the top 10% of companies generate annual TSR of 37% [Exhibit 2]

- On average, large companies grow at 6% per year, but the top 10% of companies grow at 47% [Exhibit 3]

- The vitality, or capacity for future growth and reinvention, is also very different across companies: the average vitality score (on a range of 0–100) of the ~1100 largest global companies is ~38, while the average and lowest vitality score of the Fortune Future 50 is ~72 and 61, respectively.

- On average, economic downturns have had a very adverse effect on companies: revenue growth declined by 1% on average, compared with 8% annual growth in the three prior years. Similarly, profit margins also declined for the majority of companies. But 14% of companies were able to grow both top and bottom lines during the same time periods creating Advantage in Adversity.

Now is the worst time in history to be average

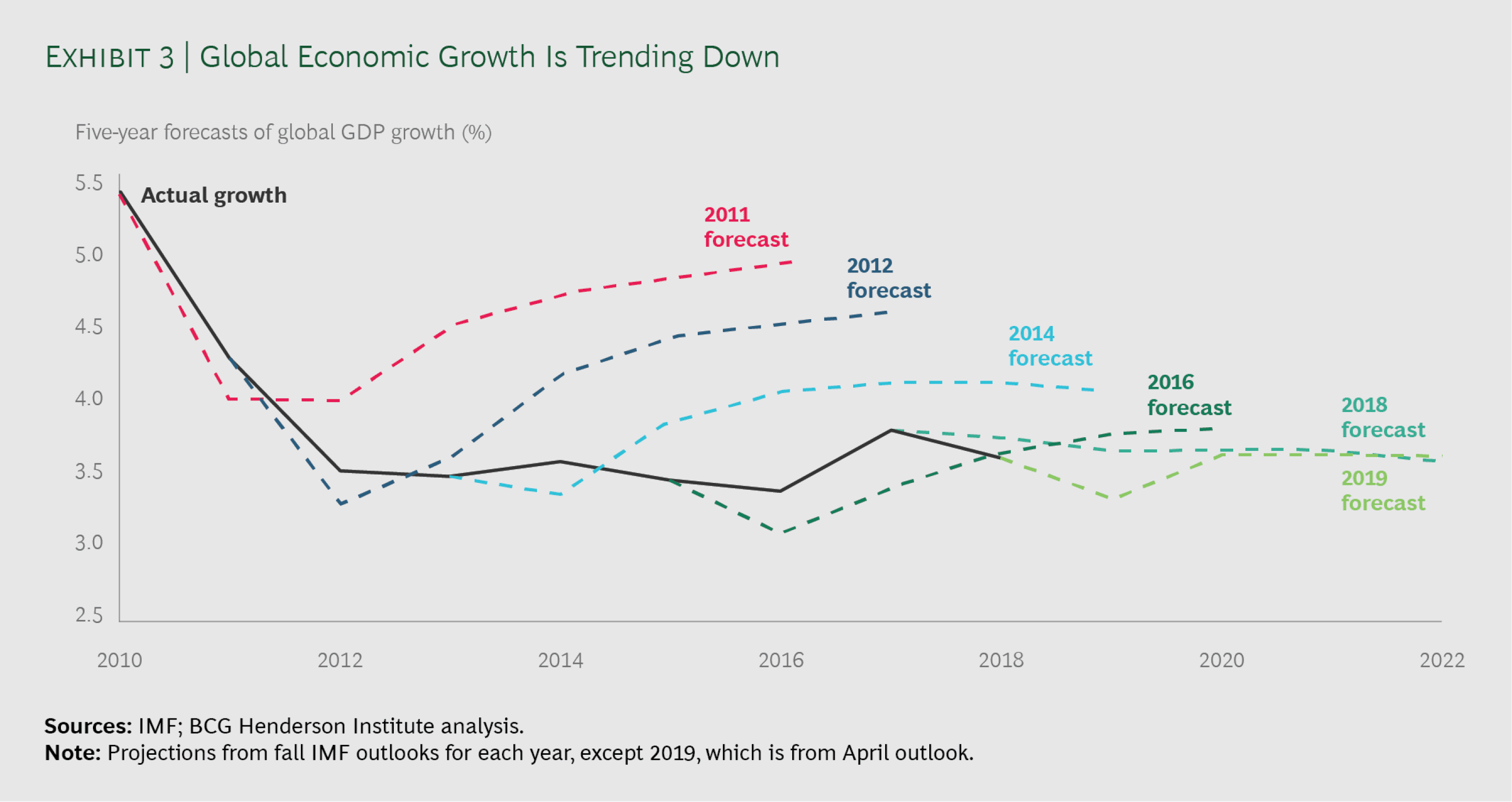

The need to be exceptional is more important than ever. Economic growth is declining globally, both in the short term, driven by cyclical factors, and the long term, driven by demographic shifts — reinforcing the imperative to beat a declining average [Exhibit 4].

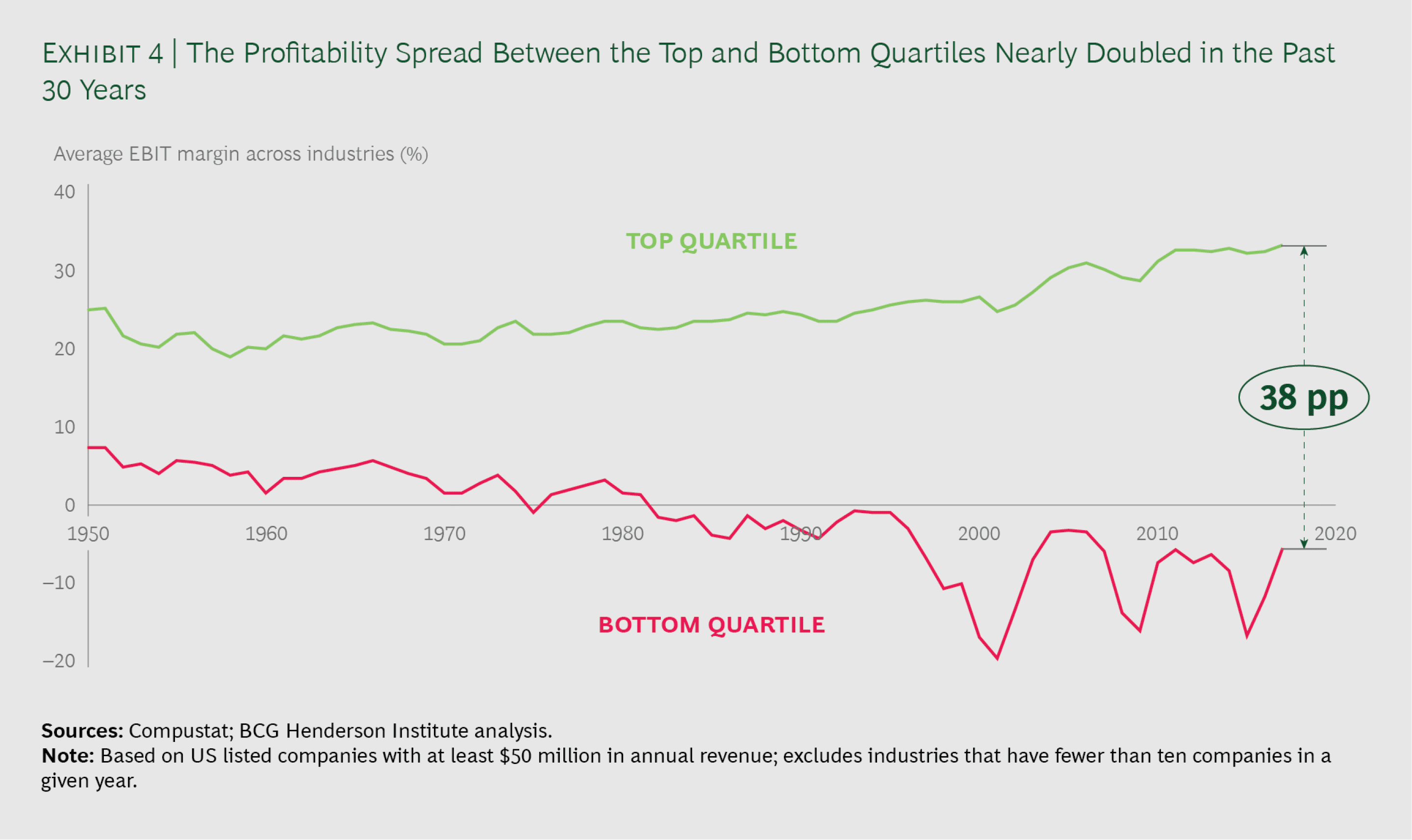

Furthermore, the spread of performance across companies is increasing, due to both declining rewards to low performers and increased rewards to the exceptional. The spread of EBIT margin between the top and bottom quartile nearly doubled over the past three decades, for example [Exhibit 5].

This is in part attributable to the rise of winner-take-all platform-based business models, which now dominate the list of the largest companies in the world by market capitalization. 10 years ago, those platforms were only beginning to emerge. The rule of 3 and 4 is effectively being replaced by a “rule of one” for many platform businesses, where second or third entrants are often unviable.

The spread of individual company performance over industry performance, effectively the value of not being an average player in your industry, has also increased.

And being exceptional, once achieved, is increasingly short-lived and in need of constant renewal. We can see this across various indicators of volatility and dynamism, including:

- Higher turnover of Fortune 100 companies(with similar trend in Fortune 500)

- Increased competitive volatility

- Acceleration of business lifecycles

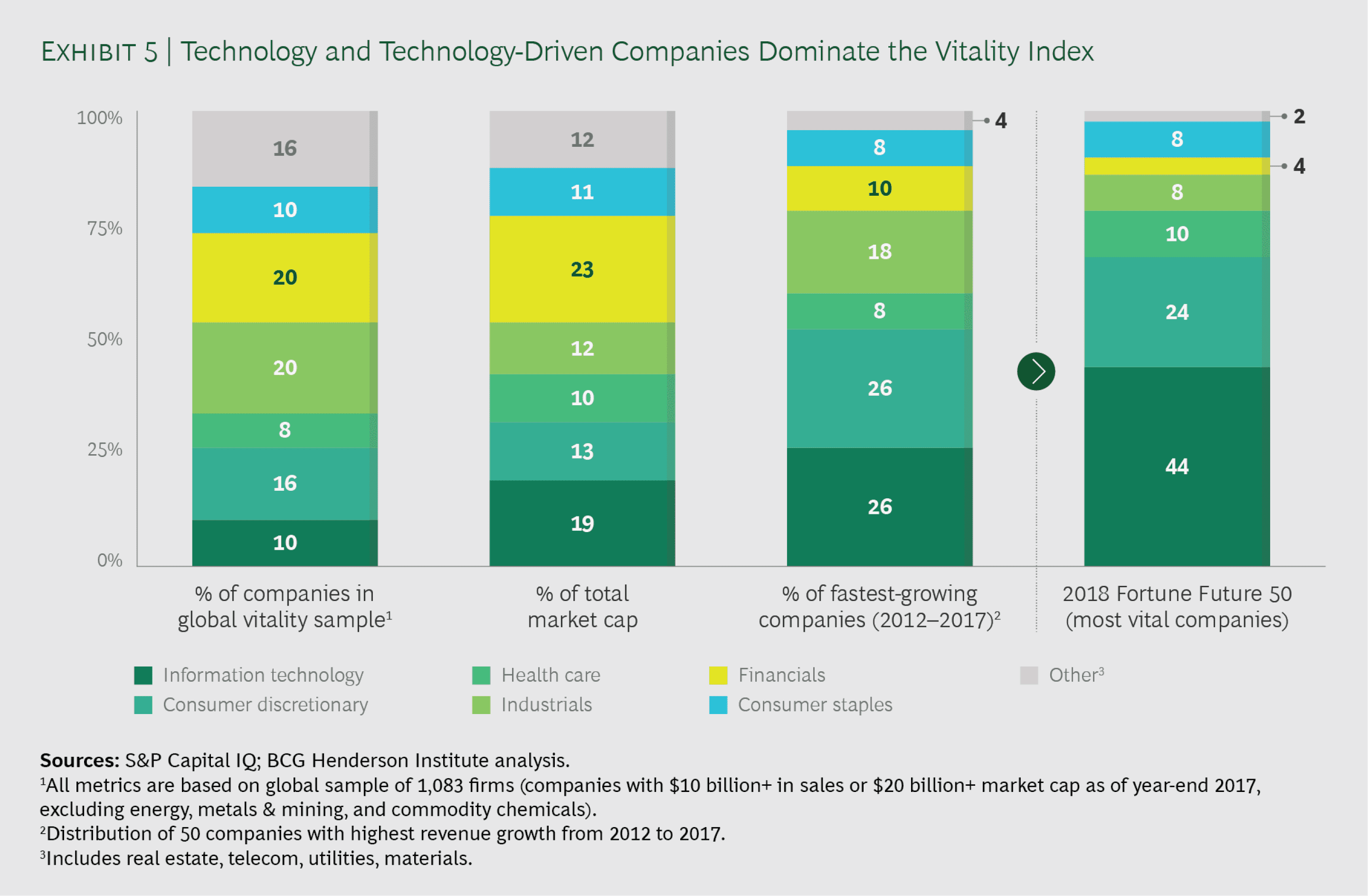

Moreover, if we look forward by examining corporate vitality, we can see that future growth potential has become massively skewed towards technology. This means that companies that are not exceptional in leveraging technology to reinvent their business and organizational models are destined to perform poorly.

Revive the art of defying averages

While avoiding being average may sound like obvious advice, a number of very common business practices — including benchmarking, best practices and incremental budgeting — can unwittingly lead to imitation and accelerate regression to the mean. How then can companies pursue the extraordinary and eschew the average?

Uniqueness mindset

Defying the average begins with a clear articulation of what is unique about a company and the value it can deliver. Look at your purpose, vision statement, and strategy with a skeptical eye and ask yourself whether a reasonable person could identify the specific industry, let alone the specific company, to which it pertains. By sharpening the articulation of what make them different, companies can create a better foundation for an attractive strategy.

Unreasonable ambition

Incremental goal setting can lead to steady, predictable improvements in results — but that’s likely to be exactly what your competitors are doing too.

Setting unreasonable goals can force imaginative thinking and the identification of new opportunities for being exceptional. It is impossible to stretch one’s strategy without first stretching one’s thinking. Use strategy games, like “destroy your business”, “think like a maverick” and “friction destroyer” to identify opportunities for creating uniqueness.

Segment, prioritize and balance

Take a fresh look at your business, geography, product and customer portfolios to understand where the best opportunities for creating and exploiting advantage lie. Ask yourself if the balance between growth and cash flow is sustainable, whether you should be investing more in growth, and whether there are positions you should be turning around or exiting. Our analysis of corporate vitality suggests that many established companies are driving short run performance at the expense of long term growth, exposing themselves to the risk of stagnation and decline.

Mass customize

Digital technology now gives us the ability to micro-segment customer needs and personalize the offering for each customer. Going beyond being unique overall, it is now realistic to be unique to each customer on each occasion. Doing so effectively and consistently creates stickiness which can be difficult to overtake.

Focus less on competitors and best practices

Business is more and more dominated by digital platforms that do not respect industry boundaries. You may believe that you are competing with a handful of large companies that make similar products, whereas your customers may be having their expectations shaped by leading digital competitors in other industries. By focusing on out-performing your direct competitors and introducing best practices from within your industry, you may be setting your sights too low and making yourself vulnerable to disruption by challengers with more unique value propositions.

Compete on the rate of learning

The combination of ecosystems, big data, machine learning and automated decision making is accelerating the rate at which we can learn in technologically enabled enterprises. We believe that in the next decade, enterprises will increasingly compete on the rate of learning. By reinventing the organization to combine people and technology in new and synergistic ways, you can sustain your edge by learning faster than your competitors about your customers’ changing needs.

Surprise and delight

Asking your customers what they want, or even measuring accurately what they are buying or browsing, may not be sufficiently forward-looking compared to your fiercest learning competitors. Analyzing and addressing the friction costs in your customers’ end-to-end processes, and surprising and delighting them by solving for these before they can articulate the need, is a bolder and more effective way of looking ahead and maintaining your edge.

There has never been a worse time to be average. The winners of the 2020s will be the ones that focus on imagining, articulating, creating and sustaining their uniqueness.