Is Google innovative and diverse, or innovative because it’s diverse?

Innovation and diversity often go hand in hand. Does diversity really drive innovation, or are innovative companies just naturally more diverse? Our societies need evidence-based answers to such foundational questions.

Every year in May, the world celebrates a ‘month of diversity’. The institution of such an awareness month shows both societies’ appreciation of the value of diversity as well as the need to promote it. The rationale for doing so is based on the dual logic of “doing right by doing good”: Equal access to opportunity is a human right, and it is also good for business.

The first rationale is now nearly uncontested in most democratic societies. The second is widely mentioned and theoretically sound: Teams comprised of diverse members are often more innovative because they can tackle problems from very different angles. It is therefore clearly true that diversity leads to more innovation. Or is it?

Unfortunately, the evidence is anything but clear, despite substantial efforts to show the causal connection. Why is this so?

- For one, there’s often no reliable data available. The diversity of managers has been systematically and widely documented only since 2010.

- Then there’s the problem of measurability: What is diversity, and how can we make it quantitatively tangible in all of its many facets?

- Finally, as we all know, correlation does not imply causation. It’s far from easy — not only to clearly measure economic success, but also to prove that diversity causally drives innovation.

Is Google innovative and diverse, or innovative because it’s diverse?

As a result, the correlation between diversity and innovation can often be demonstrated only in smaller samples, such as ones consisting of Dow Jones, CAC40 or DAX30 companies, or a narrow selection of businesses directly surveyed for complex studies. Even more problematic is the overarching question of causality: Does diversity drive innovation, or do innovative companies naturally attract people from very different backgrounds?

This is not only an academic question. It is deeply human to accept insights that correspond with our worldviews without questioning them. “Diversity drives innovation” has become a truism, but it continues to draw critics — and rightly so.

Social cohesion requires scientifically verified and constantly verifiable facts. It is on this basis that we argue and struggle to find the best ideas and strategies for our actions. If we knowingly base our actions on weak arguments, we harm the quality of social discourse long-term. Those who proclaim “follow the science” may be well advised to keep upholding the high standards of scientific inquiry in all social matters.

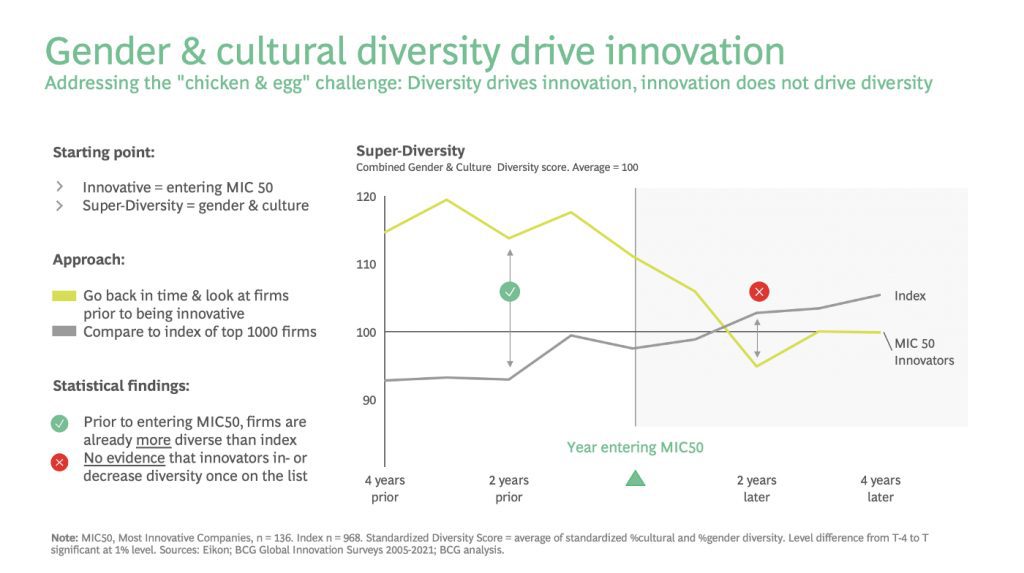

Many years before becoming innovative, firms were already diverse

Here at Boston Consulting Group (BCG), we’ve been researching the topic of innovation for 15 years. This year, for the first time, we also evaluated our treasure trove of data in terms of the diversity of innovative companies, using an “event study” methodology. We compared two groups, the first consisting of companies that made it onto our list of the world’s 50 most innovative companies at least once in the last 15 years. The second group was comprised of over 900 publicly listed companies that never appeared in our publications as one of the 50 most innovative companies.

For the statistically inclined readers, we thus use the year of first appearance on BCG’s Most Innovative Companies list as the moment to then study pre- and post- event differences in diversity between two groups of otherwise similar publicly-listed large companies. This method is not perfect as we define “innovative” as a binary variable based on BCG’s ranking methodology. Still, this variable does indeed capture firm qualities associated with innovation as MIC50 companies tend to grow faster and create more shareholder value in the years following their inclusion in the MIC50 index.

Two results surprised us most:

- Our data showed that the companies in the group that later appeared in our ranking of the most innovative companies were much more diverse many years earlier. Statistically speaking, these companies had significantly more women and different ethnicities in management, on average, many years before they were considered to be innovative companies.

- Our data also showed that innovative companies in this year’s ranking, such as Apple, Google, Siemens, Pfizer, or PepsiCo, did not automatically attract even more diversity once they were seen as being innovative on the world stage. On the contrary — after a few years, the two groups showed no significant differences in terms of attracting diversity.

What can we learn from this? Our data and methodology appear to indicate that companies are innovative because they are diverse — they are not innovative and diverse. They also suggest that innovative firms do not become more diverse, a key proposition often brought forward by those questioning the causal link from diversity to innovation. Absent better ways to unequivocally assess causality like randomized control trials, we cautiously interpret these results as strongly suggestive of a true causal link between diversity and innovation.

The broader opportunity for us all

Let’s consider the broader implications of this insight: People crossing borders create networks spanning continents and are principal drivers of cultural diversity in our societies. Their movement thus holds a latent, still much overlooked, potential to drive innovation in firms and our society more broadly. Case in point: The vaccine commonly known as “Pfizer vaccine” was originally developed by two Turkish 2nd generation immigrant founders at German company BionTech. This is not just anecdotal. As is well known, immigrants in the U.S. tend to be over-represented among founders of businesses large and small. Similar patterns do not necessarily hold in all other countries, which begs the question: Why not? How to better harness the potential of people crossing borders?

According to our own estimates & by leveraging standard economics models, global migration already contributes between 2–3 Trillion USD annually to global GDP. They do so by not just driving innovation in destination countries, but also by exerting much broader growth effects at origin. They share back ideas, give access to networks and capital and tend to start up businesses at origin. The IT industry in Egypt, or the nascent Automotive industry in Turkey owe much of their initial seeds to the Egyptian and Turkish diaspora, respectively.

Zooming out, of course, many challenges need to be overcome, and migration is not just a matter of economics. Still, let’s embrace the emerging empirical evidence for the net benefits of diversity and people crossing borders, and start asking how to actually tap into this exciting potential.