Abstract

Like humans, companies are subject to a relentless process of aging that ultimately leads to decline. For firms, decline takes the form of reduced growth and profitability, which managers usually respond to with reactive measures, such as divestments or layoffs. Such reactive measures are more costly and less effective than preventative measures, which tackle the drivers, rather than the symptoms, of decline, and which reduce the risk of passing tipping points beyond which recovery becomes difficult or impossible.

Evolution has equipped the human body with natural processes that constantly combat the drivers of aging. In addition, humans, based on their understanding of these drivers, take preventative actions that delay decline onset and promote longevity.

In this article, we outline how companies can leverage learnings from human biology and aging to identify root causes of corporate decline and enact preventative measures, to proactively and continuously combat aging.

From the moment life begins, our bodies begin to decline, driven by processes at the cellular level: Proteins are misfolded, DNA mutates, and stem cells are depleted. For humans, these cellular processes result in physical and mental deterioration, before inevitably ending in death.

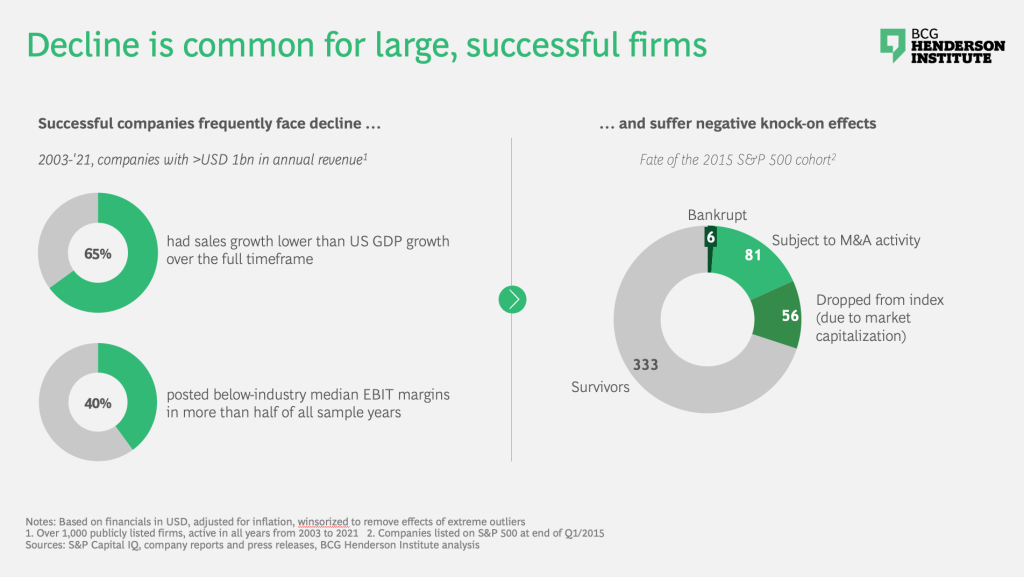

Companies, meanwhile, have no natural lifespans. Even so, they are still subject to an unrelenting process of decline — accumulating excessive structures or bureaucracy, deviating from codified procedures, and becoming increasingly ineffective at adapting to their environments. These processes ultimately become manifest in a reduction in growth or profitability, which can have negative knock-on effects — such as being acquired, dropping out of competitive rankings, or going bankrupt.

Our research shows corporate decline is alarmingly common, even for the largest and most successful firms (see exhibit 1).

Unlike humans, firms rely on costly emergency actions to counteract decline

In biology, decline and death are natural processes: Past peak reproductive years, there is limited selective pressure to delay aging, since there is little to no impact on an individual’s reproductive value. The death of an individual may in fact benefit its descendants, by making resources available to them. Indeed, there may even be collateral benefits to unrelated individuals and other species within the ecosystem, though this is not in general likely to be favored by natural selection.

The primary units of natural selection are below the level of the entire ecosystem, i.e., at the levels of individuals and gene complexes. Hence, despite the inevitability of death and the benefits it provides to a species, the human body has evolved natural countermeasures that regulate the aging process and counterbalance decline, at least leading up to and during reproductive age: For example, the process of apoptosis — programmed cell death — ensures that cells that prove pathological or useless are selectively eliminated, while stem cells serve to repair damaged organs and tissues.[1]Pandey, Shiv Shanker et al. “Programmed Cell Death: A Process of Death for Survival.” Journal of cell death, 11, 2 (2018).

Beyond these natural processes, humans — driven by an innate desire to extend life and healthspan — have for millennia taken active measures to postpone decline onset and promote longevity: Neanderthals used plants, clays, and soils as healing agents,[2]Spikins, Penny et al. “Calculated or Caring? Neanderthal Healthcare in Social Context.” World Archaeology, 50, 3 (2018). while evidence of dentistry and surgery have been found going back to before 5,000 BC. Humans primarily take two types of active countermeasures: First, preventative measures (e.g., healthy nutrition, exercise, good sleeping habits), which reduce the risk of disease, and, second, reactive measures, such as surgery or medications, which aim to reverse decline after it has begun to manifest itself.

Firms are similarly driven to avoid premature decay. But, unlike humans, they lack the biological mechanisms that counteract the aging process. Instead, research has shown, companies are overly reliant on acute reactive measures — fighting decline once it has become measurable in financial KPIs, by engaging in blunt actions, such as business unit divestments, cuts to their product portfolios, or staff layoffs. These measures are often more costly and less effective than a proactive approach, as business leaders make worse decisions in crisis situations and because their actions often tackle the symptoms, rather than the causes, of decline.

A superior approach would be for companies to take preventative steps that address the underlying drivers of aging. For example, a company could put in place a process to regularly review and prune excessive or complex procedures and structures, rather than wait until a full delayering or transformation becomes necessary to address inefficiencies and inflexibilities.

So, what is stopping CEOs from taking such preventative measures more often?

For one, aging is a surreptitious process: Companies may not notice aging until it manifests itself in reduced growth or profitability, as conventional — mostly backward-looking — metrics fail to pick up early warning signs. Often, decline only becomes apparent once pressure is applied — e.g., when companies have to react to a competitive threat or a shift in consumer tastes. Similarly, humans begin losing flexibility in their joints starting around age 30,[3]Medeiros, Hugo Baptista de Oliveira et al. “Age-related mobility loss is joint-specific: an analysis from 6,000 Flexitest results.” Age, 35, 6 (2013). but may not notice this for decades, until mobility is impaired significantly.

For companies, this issue of subtlety is exacerbated by a lack of understanding of the root causes of corporate aging.

We believe that, to close these gaps in our knowledge, we can leverage our deep understanding of human biology — to identify analogous drivers of corporate decline and proactive countermeasures to take.

Learning from human aging to understand the drivers of corporate decline

Decades of research have been aimed at identifying the cell-based processes that drive human and mammalian aging at the fundamental level. On this basis, a framework called “the hallmarks of human aging” has been established.[4]López-Otín, Carlos et al. “The hallmarks of aging.” Cell 153, 6 (2013). Details on the mechanisms underlying each hallmark of human aging described in this article can be found here. What can we learn from these hallmarks to identify the root causes of corporate decline?

1. Accumulation of structures and processes

Two closely linked hallmarks of aging are the loss of proteostasis — dysfunctions in the protein building machinery — and cellular senescence — a state of arrested cell growth in which cells cannot reproduce, but are also resistant to apoptosis, the natural process of programmed cell death. Together, these factors lead to a build-up of material that can damage nearby structures, such as misfolded proteins or “zombified cells” cells secreting damaging chemicals. Over time, this build-up may manifest itself in diseases: For example, Alzheimer’s is marked by an accumulation of tau protein tangles, beta amyloid plaques, and senescent neurons in the brain.[5]Musi, Nicolas et al. “Tau protein aggregation is associated with cellular senescence in the brain.” Aging Cell, 17, 6 (2018).

In a similar vein, companies are susceptible to an accumulation of processes and structures: Initially set up to manage increasing complexity and scope as firms grow and mature, bureaucracy can become excessive, causing high overhead costs, slowing down decision-making, or creating obstacles to internal communication or collaboration — which may ultimately contribute to a decline.

A BCG analysis covering over 1,000 companies confirms these adverse impacts of internal complicatedness — both on growth, by slowing innovation and deployment of new products, and on margins, by injecting inefficiency and costs into operations. Research also highlights that these negative effects are correlated with organizational size, implying managerial diseconomies of scale: For example, the average time to reach a decision on a non-budgeted expense was found to be more than 50% higher at large than at small firms (20 vs. 13). It is no wonder, then, that corporate leaders describe bureaucracy as a “villain” (Doug McMillon, Walmart), a “cancer” (Charlie Munger, Berkshire Hathaway), or a “disease” (Jamie Dimon, JP Morgan Chase).

2. Mutation / incorrect replication of information

Three further hallmarks of human aging are related to DNA — the genetic code stored in our cells — and its expression: As humans age, repeated cellular replication provides an opportunity for errors to accumulate as DNA is copied — driven by genetic instability, the tendency of cells to undergo mutation during replication, and telomere attrition, the gradual loss of protective caps on the end of the chromosomes carrying our genetic information. Additionally, epigenetic alterations, i.e., changes in the expression of genetic code, may occur. Together, these factors may lead to impaired cellular functions, cell loss, and the uncontrolled growth of mutated cells — cancer.

As companies mature, they codify their fundamental processes to enable replication at scale. Just like the DNA in our cells, these processes may become damaged or mutate as they are repeated again and again — which will reduce efficiency or effectiveness, ultimately contributing to decline.

This is usually driven by a combination of factors. First, there may be an information problem: If the codification itself is ambiguous, unclear, or incomplete, it is difficult to execute consistently. Second, there may be an incentive problem: For one, employees have a basic motivation to conduct their tasks in a way that is most efficient for them individually, which may prompt employees to take shortcuts, leading to process deviations. Misaligned incentives can also be caused or exacerbated by corporate policies — if, for example, employees are assigned targets, formally or informally, that cannot realistically be met when standard procedures are followed.

An example illustrating this combination of incentive problems is Wells Fargo, where — according to an internal investigation by the independent directors on the bank’s board — the “performance management system […] combined with aggressive sales management created pressure on employees”, which led to improper sales practices: “accounts were opened and products were provided to customers that they did not authorize or want”, as former CEO John Stumpf testified before the US Senate. Wells Fargo paid over USD 3 bn in settlement charges linked to these sales practices. Moreover, the Federal Reserve capped the size of the bank’s balance sheet, limiting its growth potential.

Under new leadership, Wells Fargo has since taken significant steps to regain the trust of customers as well as regulators and emerge stronger from this crisis — by abolishing product sales targets and shifting the focus of performance management towards enhancing the customer experience, by implementing a comprehensive “mystery shopper” program, and by strengthening the compliance and risk management functions.

3. Impaired sensing

Two further hallmarks of human aging contribute to a loss in cells’ sensing and signaling capabilities over time: Deregulation in nutrient sensing induces proteins to falsely detect an abundance of nutrients in metabolic pathways, while altered cellular intercommunication can cause cells to become locked into one line of signaling. As a result of these processes, cells invest less in maintaining and repairing themselves and reduce their range of functions — which has been strongly linked to an impaired ability to fight infections.

Similarly, mature companies that have experienced success are prone to focusing on replicating past approaches, while being less receptive to external signals — a phenomenon called the success trap. Moreover, as corporations grow in size, they become insular, with internal information flows drowning out external signals and fewer employees coming into direct contact with customers or competitors. As a consequence of this impaired sensitivity to market developments, companies can miss out on vital trends, resulting in an inability to adapt, which may culminate in a decline.

This phenomenon is prevalent even in the relatively young tech industry, where, over the past decades, several previously dominant players have failed to adapt their offerings to technological innovations and shifting consumer tastes: For example, IBM, which held a market share of up to 70% in mainframes in the 1960s and 1970s, did not react in time as competitors, such as Apple, Compaq, and Dell, introduced personal computers — its eventual turnaround and success story requiring a radical refocusing of the business mix towards consulting services and software offerings. Similarly, Nokia, once the leader in mobile phones with a peak 51% global market share in 2007, did not effectively address the potential of smartphones and the mobile internet — a misstep it has still not recovered from, with its net sales standing at less than half of their late-2000s golden-age. Finally, MySpace was the leading social network and the most visited website in the US in July of 2006. However, it failed to recognize the threat of new entrants, such as Facebook, which offered a superior user experience — and in 2018 was receiving around 8 million monthly visitors, vs. Facebook’s 3 billion today.

4. Reduced renewal / adaptive capacity

The two final hallmarks of human aging influence energy production and regenerative properties: Mitochondria dysfunction reduces the effectiveness of energy production within the powerhouse of the cell, becoming manifest in a wide range of pathologies, including fatigue and weakness. Meanwhile, stem cell exhaustion refers to the gradual depletion of stem cells, which leverage their unique regenerative properties to mend damaged cells and tissue.

Like cells in the human body, companies lose their adaptive capacity over time, becoming locked into certain strategies or approaches. This may be driven by past actions, such as promises made to investors or supplier contracts signed. More commonly, however, it is a mental issue: Leaders may become too personally invested in the success of certain strategies, committing to them past the point of optimality. Moreover, managers may become increasingly entrenched in their positions, trying to defend status and power by engaging in empire-building or by acting in an excessively risk-averse manner. As a result of these developments, a firm’s entrepreneurial spirit diminishes, as does the capacity for reimagining the firm’s purpose and business model — a key driver of corporate rejuvenation. Together, these factors impair the ability of companies to act on recognized threats or opportunities.

A case in point is Polaroid, the American company[6]We are referring to the original Polaroid Corporation, which went bankrupt in 2001, not Polaroid B.V — the Dutch photography company that acquired and revived its brand. that invented instant film and cameras. Polaroid was one of the earliest investors in digital photography, spending close to half of its R&D budget on the field in the late 1980s. However, top management hesitated to bring the new product to market, as a bet on digital photography would have fundamentally changed the firm’s business model away from consumables towards hardware. Their fear was exacerbated by the earlier failure of the company’s instant home video system “Polavision”, which did not capture a significant market share due to design flaws and a lack of demand. Ultimately, Polaroid launched its digital camera in 1996, almost a decade after the company had created the first prototypes. By then, Polaroid had ceded significant market share to competitors and could not regain its position, declaring bankruptcy in 2001.

Emulating humans, companies need to establish proactive countermeasures

In humans, the joint effects of the hallmarks of aging ultimately result in decline and death, as the natural processes that regulate and counteract aging are eventually overwhelmed. However, leveraging our understanding of the drivers of aging, humans have developed active countermeasures, both preventative and reactive, that significantly delay decline onset, reduce its severity, and prolong life: As a result, average human life expectancy has increased from around 30 years in the early 1800s to over 70 years today, with these advances extending well beyond reductions in child mortality.

Companies lack natural, built-in processes to combat aging. Moreover, they rely on emergency responses to decline, which are often ineffective and costly. This is exemplified by the case of tire company Firestone,[7]This refers to the original Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, which was bought by Bridgestone in 1988 and later used as a brand name for tires and other products. which experienced more than seven decades of continuous growth and success after its founding — until 1972, when its European competitor Michelin introduced a new, superior radial tire design to the US market. This development was not a surprise to Firestone, which had witnessed the popularity of radials in European market in the 1960s. Despite this, Firestone failed to take proactive steps, waiting until the radial tire disruption escalated. Forced to engage in hasty, reactionary measures, Firestone invested significantly into radial tire production, building new manufacturing plants — but had conducted limited R&D and did not effectively change their production processes to match the product shift. The results were plants running at half capacity, inferior quality products, and costly recalls — ultimately culminating in Firestone’s takeover by Japanese competitor Bridgestone in 1988.

Rather than repeat these mistakes, companies should learn from human biology, taking preventative measures to counteract decline.

1. Accumulation of structures and processes

In humans, the natural process of apoptosis prevents unwanted cell growth and accumulation.[8]Shen, Jie, and John Tower. “Programmed cell death and apoptosis in aging and life span regulation.” Discovery medicine, 8, 43 (2009). In addition, research indicates that we can actively combat cellular senescence by following nutritional guidelines and observing caloric restrictions.[9]Fontana, Luigi et al. “Caloric restriction and cellular senescence.” Mechanisms of ageing and development, 176 (2018).

Emulating these mechanisms, corporations should establish processes that pre-empt an excessive build-up of structures and bureaucracy. This includes defining clear organizational design principles, as well as conducting regular reviews and pruning of structures. An overburdened bureaucracy can be prevented by establishing clear sunsetting practices to pre-plan how and when projects and the processes and committee structures associated with them will end.

A case in point is Haier, which started out as a refrigerator manufacturer in Qingdao, China in 1984, producing for the local market. Over the following decades, Haier continuously scaled up its product portfolio and expanded its international footprint, eventually becoming the world’s leading white goods manufacturer, with a 10% global market share in 2015. Throughout this journey, Chairman Zhang Ruimin was wary of the threat of Haier developing “big enterprise disease” and continuously updated Haier’s management model: In 2005, Mr. Ruimin divided the 80,000-person organization into 4,000 autonomous “microenterprise”, intended to help Haier businesses gain proximity to their customers, aiding localization efforts as the firm entered new markets. Then, in 2015, Mr. Ruimin saw further opportunity for improvement, recognizing that user needs had become even more complex in the IoT era. In response, Haier launched an ecosystem strategy, where the individual “entrepreneurial cells” — while continuing to run like independent startups — leverage a common platform infrastructure, ensuring that the internal linkages mirror the connectedness of consumers’ products, thus preventing siloing.

2. Mutation / incorrect replication of information

To inhibit the accumulation of errors in replicating genetic information, cells leverage a conservative copying methodology — always pairing a strand of the original DNA molecule with a copied strand in a new double helix. This is then exhaustively proofread and errors are repaired. Beyond these natural processes, humans can actively reduce the risk of mutation by ensuring that the DNA is not unnecessarily damaged in the first place — for example, by avoiding excessive UV radiation or applying sunscreen.

Similarly, companies should take active steps to inhibit a mutation of processes that may drive inefficiency and ineffectiveness. This involves, first, strong codification: A clear, complete, and unambiguous description of the steps involved, which needs to be conveyed to employees via regular trainings.

Global fast food market leader McDonald’s exemplifies successful codification, which has enabled it to provide a remarkably consistent offering and customer experience across its 38,000 global locations, despite more than 80% of its restaurants being franchisee-owned. This is because, as McDonald’s began to grow its franchise, it established Hamburger University, a training school for franchise managers that emphasizes “consistent restaurant operations, procedures, service, quality, and cleanliness.” Today, the university operates 8 international locations, with over 330,000 managers having completed courses and all new franchise owners spending at least 5 days on campus. More than 40% of McDonald’s global leadership have attended Hamburger University, including former president Mike Andrews.

In addition, firms need to proactively address potential incentive problems: In a healthy corporate setting, this should not only rely on monitoring and incentive contracts (or threat of sanctions). Rather, firms should establish a strong purpose, tying the “how” of the process to its “why”, i.e., the broader goals, values, and principles of the company, thus generating buy-in among employees. Companies can also designate champions within the organization that live these values and can serve as role models and multipliers.

For example, American online shoe and clothing retailer Zappos has established a peer-to-peer recognition program, whereby each employee is given USD 50 per month to award a coworker that has gone above and beyond to “deliver WOW” to customers. Moreover, employees can nominate one another for awards — with stand-out workers receiving, for example, a special, reserved parking spot or even a physical cape.

Finally, firms need to recognize that, while mutation is a potential driver of decline, it can also be beneficial: In a biological context, the combination of mutation and natural selection enables evolution, yielding improvements in efficiency or effectiveness and allowing adaptation to new or changing environments. Learning from biological systems, companies should set up their codification processes to be evolvable and to capture beneficial mutations: This necessitates leaving room in scripted processes for individual discretion, whereby employees can leverage their imagination to achieve a superior outcome. This needs to be coupled with a thorough analysis of which deviations were successful, and why, as well as adapting the script accordingly.

3. Impaired sensing

To remain receptive to external signals while growing and maturing, corporations should set up formal systems and structures for monitoring external developments and integrate discussions on findings into leadership meetings. Hiring practices should be tailored to enhance the diversity of backgrounds and perspectives within the firm.

As an example, Tata Consultancy Services, the Indian IT solutions and consulting provider, launched the Co-Innovation Network (COIN) in 2006, an ecosystem purpose-built for identifying disruptive technologies early, by bringing together over 2,500 start-ups, research institutions, VCs, and corporations. This program has helped Tata to stay at the forefront of innovative solutions relevant to their Fortune 1000 customers — for instance, through COIN, Tata collaborated with Stanford University in a 5-year project to develop a suite of new data privacy tools, keeping in step with its Western rivals IBM and Accenture.

4. Reduced renewal / adaptive capacity

In humans, stem cells serve as a core repair system: In their basic state, these cells are pluripotent — able to take many specialized cell forms in order to replace other types of cells, e.g., in muscles, blood, or the brain. Moreover, stem cells have the ability to continuously self-replicate. As such, these cells can ensure functionality is retained through a process of constant renewal. Beyond these natural mechanisms, humans can also take proactive steps to maintain their adaptivity: Physically, stretching exercises preserve flexibility.[10]Cristopoliski, Fabiano et al. “Stretching exercise program improves gait in the elderly.” Gerontology, 55, 6 (2009). Mentally, creativity and ingenuity can be retained by regularly engaging in intellectually stimulating tasks — such as reading or learning languages — and by socializing.

In companies, retaining adaptivity and the capability for renewal, even as the firm ages and its managers become more tenured, requires shaping an appropriate corporate culture. This includes fostering an entrepreneurial mindset, characterized by a desire to take risks, as well as high energy and agility.

Towards this end, tech giant Cisco has, in the past, employed a unique “Spin-In” model: Upon recognizing a disruptive technology, Cisco assembled a team of engineers to work on it outside of the company, in a dedicated start-up. Cisco would fund and closely monitor the firm, before eventually re-acquiring it and integrating its technology into their product offerings. This program enabled Cisco to quickly bring new technologies to market, e.g., in the data center technology space.

Moreover, companies need to encourage experimentation and foster the ability to scale up winners. For example, since 2019, PayPal holds its annual Global Innovation Tournament, where employees can submit ideas and winners receive funding. Crowdsourcing new ideas have led to over 4,000 real-world innovations, many of which have since been operationalized, including an AI-powered framework that triages failed customer interactions and generates solutions automatically, thereby reducing customer service management time.

Finally, companies need to prevent becoming locked into mental models by systematically harnessing imagination. This can be achieved by actively seeking out surprises and the unknown, establishing heroic goals and reducing the costs of failure — leveraging the power of play to create a de-risked environment. For example, to boost engagement with novel ideas, PayPal invites all of its 30,000 employees to place wagers on the ideas submitted in its innovation tournament — rewarding successful predictions with tokens that can be redeemed for a range of experiences, such as skydiving with colleagues or learning martial arts directly from CEO Dan Schulman.

Like humans, companies are subject to a relentless process of aging. To counteract this, they should draw inspiration from human biology, proactively putting in place rejuvenation measures that continuously counteract the root causes of aging, postponing decline onset and promoting longevity.

Beyond this, leaders should also keep in mind that decline and death are natural and necessary processes — not just in biology, but also within a company’s portfolio of business units. Because resources are limited, old ideas and business models must regularly make room for new ones: A stagnating business unit must die so that budget, talent, and management attention can be reallocated. To be successful in the long-term, companies must embrace the ephemeral nature of their business units, as well as their sources of competitive advantage, and actively engage with the processes of decay and renewal across their portfolios.