75% percent of ambitious change programs fail to capture long-term value.[1]Based on self-reported CEO data 50% of change programs fail to achieve their objectives; the failure rate rises to 75% for more complex and ambitious programs. … Continue reading Despite these grim odds, globally, organizations spend $10 B annually on change management efforts.[2]ALM Intelligence, Competitive Landscape Analysis: Change Management Consulting, 2016. That is understandable in some ways — in our evolve-or-perish environment, organizations cannot afford to stay still. But more fundamentally, it suggests that organizations need to rethink the “tried and tested” approaches to change management. Our research suggests that change efforts and leaders fall victim to 10 conventional and flawed “change-isms” — mental models, assumptions, and frameworks prevalent in change management.

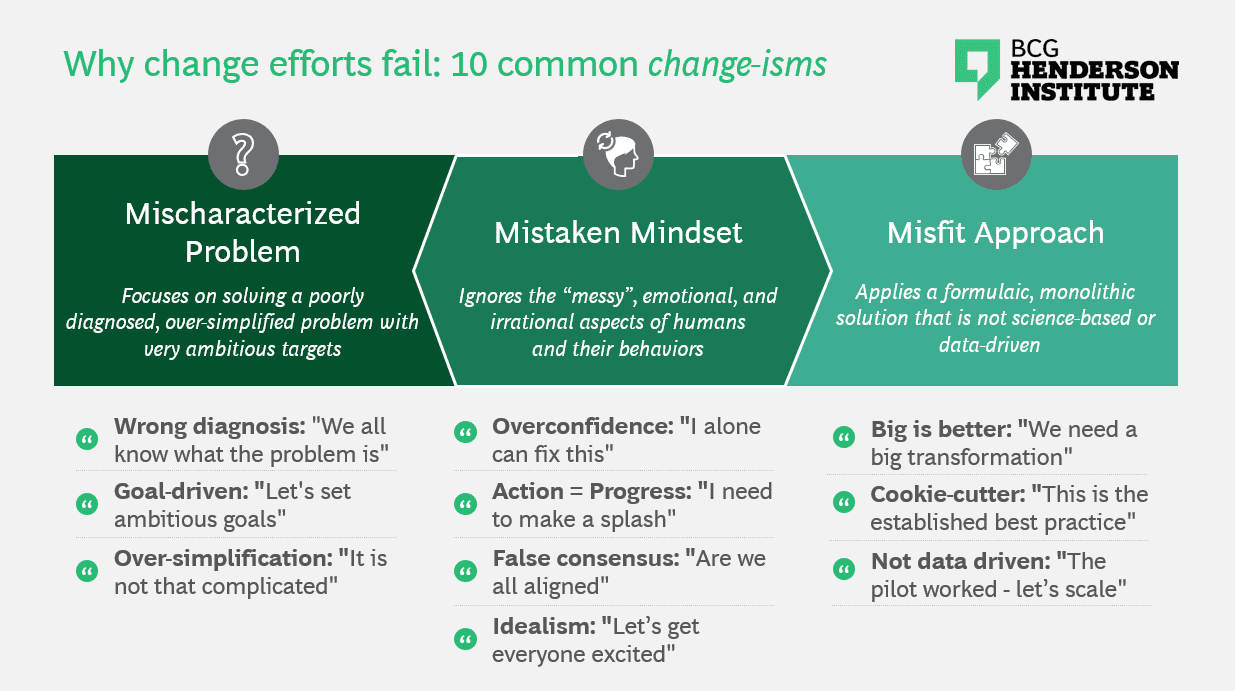

These change-isms fall into three categories:

- Mischaracterized Problem — focuses on solving a poorly diagnosed, over-simplified problem for example by assuming that the problem is the inverse of the solution

- Mistaken Mindset — ignores the “messy”, emotional, and irrational aspects of humans and their behaviors upon which change depends

- Misfit Approach — applies a formulaic, monolithic solution that is not science-based or data-driven

To avoid falling victim to one of our “change-isms”, we will not offer solutions in this piece — instead, we will focus on dissecting and understanding the why.

Mischaracterized problem

“We all know what the problem is.” Leaders often bring their own assumptions. Not enough time is dedicated early on to understanding and exploring the problem(s) and its root causes. For example, a business may focus on employee attrition as the problem. But that confuses symptom with the cause — the key is to understand why employees are not sticking around. There is always a choice to allocate time between understanding and framing vs solving, and a strong tendency to shortchange the former.

→ Reframe the “ism”: “Let’s spend more time understanding the root cause and assumptions we are making.”

“Let’s set ambitious goals.” Leaders prioritize discrete outcomes and targets over insight and process. Change efforts quickly become an execution problem, with the goals being pre-determined, simplistic, and often oblique to the true problem. This approach minimizes early exploration over the scope of the problem, discourages open and candid discussion over what is truly impactful and feasible, and prioritizes headline “results” over meaningful, long-term impact. For example, a CEO announces a goal of increasing digital adoption by 20% to catch up to industry benchmarks), without analyzing why that is meaningful or how it is achievable.

→ Reframe the “ism”: “Let’s understand the problem first, and then set goals.”

“It is not that complicated.” Oversimplification is a common misstep in change management initiatives. Complex problems are reduced to a linear sequence of tasks and a Gantt chart type project management approach.[3]https://bcghendersoninstitute.com/strategies-of-change-27fe879caac3 Or the solution is assumed to be the inverse of the problem. Often, change leaders do not take the time to parse out different parts of the problem, or deal with challenges around interdependency and execution. As a result, they take a monolithic approach to change and a solution is applied indiscriminately and uniformly across different components. For example, a large food manufacturer sought to modernize and expand international operations through the adoption of a new software. Believing that a linear implementation of the technology would allow them to reach their goals, they failed to appreciate and address interconnected business processes. Instead of growing sales, this oversight caused a 10% drop in total annual sales that year.

→ Reframe the “ism”: “It might not be that straight-forward; let’s deconstruct the problem into its diverse and unique traits and then find solutions for each”

Mistaken Mindset

“I alone can fix this.” Just like the 93% of Americans who think that they are better than the average driver,[4]Svenson (1981) many leaders are overconfident in their ability to influence change. As a result, leaders tend to overlook feedback and signs that indicate the initiative may not be as successful as it is believed to be.

→ Reframe the “ism”: “Why have efforts not worked in the past?”

“I need to make a splash” Leadership changes are often made with the intent of driving the evolution and transformation of a business. Therefore, it’s unsurprising that new CEOs face pressure to make immediate changes. However, rushing to act, before understanding the critical context of a change effort tends to manifest in one of two ways. Radical, ambitious change efforts, which overlook the limitations of the organization, are mandated. Or a flurry of loosely linked initiatives, workshops, and trackers are launched that create the appearance of progress but do little to drive actual change. Leaders’ bias towards action can lead to premature change efforts where the true challenge is unaddressed, and activity is conflated with progress.

→ Reframe the “ism”: “Let’s make change where it is truly needed.”

“Are we all aligned?” Leaders often look for agreement at the cost of productive dissent. Even if it is on the wrong solution. Team members may be reluctant to raise issues and surface warning signs. A culture of grudging compliance takes hold, dissent flows into backchannels, and progress stalls or is reversed. In some companies, alignment may be coercive, but more often there is a culture of passive, tacit agreement. This was the case at a car manufacturer. Their culture was known for a “nod” which was given to acknowledge but avoid responsibility or rocking the boat. The unintended consequence was a general unwillingness to speak up to challenge or assign accountability which ultimately led to a safety flaw that caused numerous deaths. The BCG Transformation Check, which analyzed 4000+ global transformations between 2020–22, found that the biggest factor in increasing the chances of a transformation’s success was two-way communication between leadership and employees. This alone can increase success by more than 50%.[5]BCG Transformation Check 2020–2022: Transforming in the “New Now:, April 2022

→ Reframe the “ism”: “What are the reasons this may not work?”

“Let’s get everyone excited!” Change comes with costs. Team members often have legitimate fears about how change efforts will affect them. Leaders should be positive but honest, confronting the good and the bad. Acknowledging the full range of emotions that surface before a transformation is one way that leaders show respect for their employees. A study conducted by MIT Culture X found that ‘feeling respected’ is the single biggest predictor in positively rating a company’s culture. This includes employees feeling that they are not “viewed as disposable cogs…or treated like children.”[6]https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/10-things-your-corporate-culture-needs-to-get-right/

→ Reframe the “ism”: “Let’s consider why people might not be excited — what concerns and worries them”

Misfit approach

“We need a big transformation.” When organizations envision change, they think of a large transformation–a course correction to steer the wayward ship back on the right header. Such moves are often complicated, costly, and even existential in nature. However, change takes time and should not be viewed as a “one and done” process; it should be pre-emptive and rooted in learning. It’s common to see leaders announce large-scale transformations which are given grand names as to imply that they will be THE solution to the firm’s challenges (e.g., “Vision 2030”, “Customer Centricity Transformation”). New product launches require unique strategies depending on the context and objectives — change efforts require an equally considered approach tailored to the specific desired changes and organizational context.[7]https://bcghendersoninstitute.com/your-change-needs-a-strategy-2510061f51a9

→ Reframe the “ism”: “Where do we need to make big changes and where can we make incremental, sustained ones?”

“This is the established best practice.” Leaders defer to outside “expertise” or “best practices” without systematically looking at the data. In doing so, they fail to take an independent, evidence-based approach towards change. Coupled with limited experimentation, this results in short-term fixes, at its best. To illustrate this “ism” consider a leading US airline’s attempt to challenge a low-fare carrier. The firm focused on adopting the most visible features of the low-fare carrier (e.g., casual crew uniforms, increased flight frequency, no in-flight meals) but failed to understand why these tactical strategies worked. The features, such as casual uniforms, were an outcome of something deeper — the employee-centric culture and management philosophy of the low-cost carrier. Despite the airline’s best efforts, they continued to lose share to the budget carrier and ultimately shut down their specific offerings.

→ Reframe the “ism”: “What approaches do our data support?”

“The pilot worked. Let’s scale.” Once data is collected, it’s tempting to overanalyze and then make large-scale over-generalizations. Thus, for example, decision-makers may green light a massive overhaul based on a single small pilot, without further reflection or analysis. One familiar example of this is the Arch Deluxe endeavor. In the 1990s, McDonald’s introduced the Arch Deluxe burger — a more sophisticated and slightly expensive burger. This was in response to declining sales in the adult segment. Tested through a focus group, McDonald’s decided to scale it across the country. However, the dangers of extrapolating from one focus group (which was not truly representative of the McDonald’s customer base) proved fatal, as the campaign failed costing McDonald’s hundreds of millions of dollars.

→ Reframe the “ism”: “Why might this pilot not scale well?”

Putting strategy into action: devising a change effort that averts these 10 follies

These “change-isms,” while not surprising, are persistent and pernicious. Over the upcoming months, we will be exploring ways to combat them and propose approaches and tools that are informed and backed by behavioral and cognitive sciences. To identify requirements for a principled approach, we will be researching and answering the following questions:

- What is the evidence-base for effectiveness of common traditional change management approaches and tools? Where do these approaches fall short?

- How can learnings from the social and behavioral sciences inform a human-centric approach to change management?

- How can organizations leverage tools and approaches informed by behavioral science to avoid these change-isms and yield a better outcome?

The authors thank their colleague Kateryna Gudziak for her thoughtful contributions to this article.