“Change is the only constant in life,” a truth proclaimed by Heraclitus over two millennia ago that also applies to today’s corporations—more than ever, in fact—with a turbulent environment marked by ever-accelerating technological change. Despite this, successful corporate change remains elusive, with only a quarter of transformations leading to financial outperformance over the short and long term.

One underlying issue is that change is often treated as monolithic: one type of challenge requiring one type of solution. Success is considered to depend only on how this solution is executed—that is, the quality of “change management.” We argue that change must instead be treated as a strategic problem, varying the approach to change depending on the type of challenge encountered and the internal characteristics of the company.

Two paths to success

To illustrate this idea, look at the very different approaches Microsoft and Spotify took to adopting cloud technology.

Microsoft, an established and sizable company with a hierarchical structure, was seeking to conduct a large-scale transformation to remain innovative. Cloud technology was a key part of this transformation, serving as both a new product in itself, as well as a new delivery channel for the extant offerings. The transformation, initiated in 2012, gained momentum with Satya Nadella’s appointment as CEO in 2014. Formerly head of the fast-growing cloud computing division, Nadella made it his mission “to rediscover the soul of Microsoft.” His leadership was instrumental in revitalizing the company, driving innovation, and increasing cloud revenue, which now represents more than half of Microsoft’s total sales and is still increasing year over year. We will use this case study to explore the role of leadership in driving change.

A contrasting example is Spotify, a smaller company with a flat structure consisting of modular squads—fostering peer-to-peer skill exchange and interdisciplinary knowledge sharing. For Spotify, moving to the cloud was a way to streamline operations and enable teams to focus on new features instead of managing on-premise data centers. The driving force for this change was not top leadership but the engineers responsible for data center management. According to Director of Engineering Ramon van Alteren, “The net result was that group of engineers, some of the most deeply respected at Spotify, ended up being advocates for our cloud strategy.” Spotify successfully migrated to the cloud by 2017 and closed all on-premise data centers by 2018. Using this case as inspiration, we will explore the role of change champions and peer networks in bringing about successful change.

Both Microsoft and Spotify succeeded, despite very different approaches to change. We argue that this is because they matched their change strategies to their specific organizational structures and challenges. However, these are just two of many examples of different situations in which companies may find themselves. While we can’t examine each case individually, we can employ innovative methods to explore these contingencies more deeply.

Universal change simulator

To this end, we built a change simulator that allows us to identify the effectiveness of different change strategies in different situations. This simulator uses an agent-based model, with numerous agents representing employees interacting within an organization, revealing emergent behaviors and patterns in change adoption.

The unique feature of agent-based modeling is allowing agents to exhibit their own behavioral preferences. Our model enables us to adjust factors such as employees’ openness to change, their receptiveness to the influence of peers and leadership, and their ability to cope with uncertainty. The agents are embedded in a network of influence, which reflects the structure of an organization. Our model enables us to simulate different situations by modifying the parameters of the organization these agents operate in—such as size, structure, and the strength of the influence peers and leaders exert.

To this internal context, we can then introduce external challenges, such as new technology that triggers a need for change in the company. The model allows for adjusting characteristics of the challenge—its scale, depth, reversibility, and predictability.

By leveraging the model to create different contexts—such as varying internal situations and types of challenges faced—we can test the effectiveness of various change strategies. These strategies range from simple incentivization of behaviors, to enforcement, to information sharing, or the amplification of individual agents. We measure three key elements of success when comparing the strategies: the proportion of employees adopting the change, the speed of adoption, and the robustness of a strategy across the number of simulations we run.

Horses for courses

We use our simulator to assess the adoption of a new technology in organizations with different characteristics: first, a hierarchical organization; second, a company with strong and homogeneous peer networks; and, third, a firm characterized by autonomous employees. For each situation, we start by observing how change propagates through the organization, driven solely by the promised productivity increase associated with the new technology. We then compare this to three different intervention strategies designed to drive change adoption. This approach allows us to assess the effectiveness of each strategy and determine how the drivers of success vary depending on the situation.

Change strategy 1: Inspired by Microsoft, this strategy leverages a leadership figure to drive change top-down. This strategy employs interventions that enhance the influence of the leader, the central node of the organization—strengthening the influence leadership has on the rest of top management and, subsequently, on the rest of the hierarchy. In real life, think of tactics such as cascading hierarchical performance contracts. We call this strategy Amplifying the leader.

Change strategy 2: Spotify’s collaborative learning approach inspires the second strategy, which leverages advocates of change within peer networks to propagate change through established relationships within the organization. By creating incentives for adopting the change, this strategy encourages specific individuals to embrace it. These employees then champion the change within their networks. Imagine tactics such as reward programs for change adopters, bonuses, or career advancement linked to adopting the change. We name this strategy Creating change champions.

Change strategy 3: With the third strategy, we aim to test how organizations can achieve change without strong peer networks or central leadership figures. This strategy relies on employees’ internal motivation to change, based on the positive impact they expect the change to have on their individual performance. Tactics such as success stories are examples of this approach in practice. We call this strategy Educating and empowering.

Three situations illustrating the contingency of change strategies

Situation 1: Hierarchical organization centered around leadership

The first situation we explore is a hierarchical company with a powerful leader on top. In this situation, hierarchy is established through a network of influence where nodes are organized in a branching tree structure. Each node is connected to a single parent node, which in turn connects to higher levels of the hierarchy, resembling a typical corporate structure. At the top is the CEO with subsequent levels of management linked below. Decisions cascade down from the top and employees are primarily influenced by their direct managers, rather than their peers. These conditions are typically found in large, established organizations with a well-defined chain of command. Picture, for instance, an international financial institution or a global tech company, driven by the vision of a charismatic CEO.

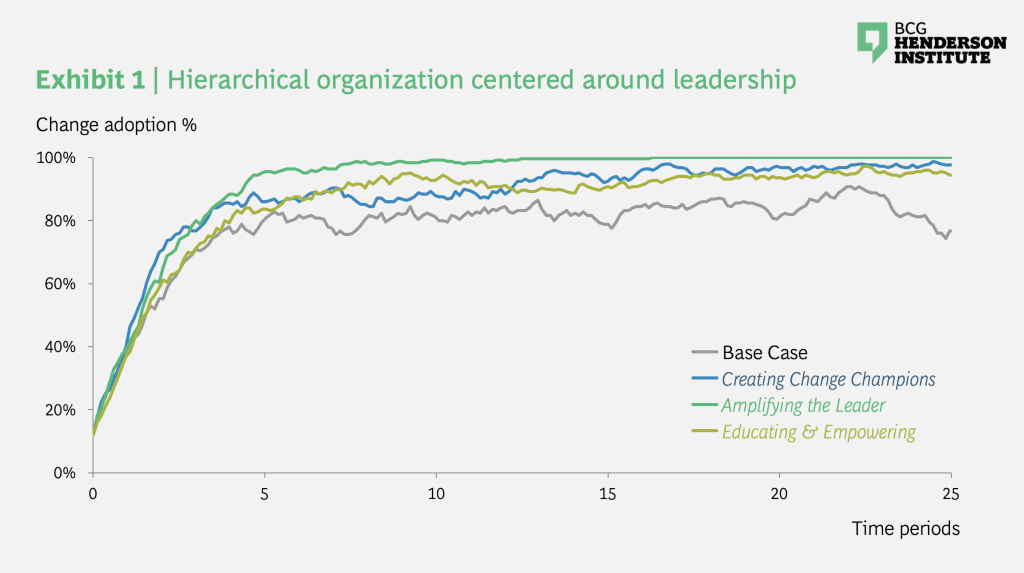

The most natural strategy in this situation is to rely on the power of hierarchy. When a leader adopts the change and directs their reports to do the same, the change is expected to spread throughout the organization via the chain of command, reinforced by consequences for noncompliance. However, this approach has its limitations. As shown in Exhibit 1, this base case never achieved 100% change adoption. Relying solely on hierarchy leads to relatively volatile results, with some simulations exceeding 90% adoption and others falling short of 80% and the median plateauing at ~77% adoption.

As noted by economist Avinash Dixit, the costs of monitoring and communication increase as the system expands, leading to diminishing returns associated with growing distance from the central authority. Our model corroborates this, revealing the limitations inherent in the network structure itself: while the hierarchical setup enables decisions to cascade, it also creates silos. Teams in hierarchical organizations are primarily connected to their leaders and, through them, to the CEO, but not necessarily to each other. As a result, if their direct superior does not adopt the change, there is no broader peer network to influence adoption. Thus, hierarchy alone may be insufficient for ensuring that middle management is on board with the change: the top leaders’ influence needs to be amplified.

To understand how we can strengthen the influence of leadership, we first need to explain why employees in our simulation decide to switch from their status quo behavior. An employee adopts the change based on its perceived utility, determined by three factors: internal preferences toward change, the influence of peers who have already adopted the change, and the employee’s receptivity to that peer influence. Our simulation assigns weight based on the strengths of influence of each node, reflecting the varying levels of impact among employees.

By implementing Strategy 1: Amplifying the leader, we increase the weight their influence has on the utility functions of employees not just at the next hierarchical level, but across the organization. Think of this as employees receiving communication and guidance from top leadership, even if they do not directly report to the CEO. Amplifying the leader’s influence ensures that change cascades through the organization—middle managers, as well as their teams, get on board. As shown in Exhibit 1, this leads to 100% adoption of the change in approximately ten time periods—which is robust across our simulations.

The other two change strategies we explore also enhance the effect of hierarchy, but are not as stable or as successful as the Amplifying the leader strategy. As demonstrated in Exhibit 1, the Creating change champions strategy achieves close to 100% adoption, but it takes longer to achieve this result and is also more volatile. This highlights the limitations of relying on peer networks within a hierarchical structure, where influence travels through the leaders to reach isolated teams: the change champions can influence only their immediate peers, providing merely incremental enhancement to the effects of hierarchy.

Educating and empowering by providing information and relying on employees to adopt the change without leadership influence has a very similar outcome—it offers a modest improvement by helping employees understand the perceived benefits of the change, making them more responsive to shifts in utility. However, it lacks the potential to achieve the full adoption and stability of a strategy that relies on leadership influence.

Situation 2: Flat organization with strong peer network

Now, let’s consider a different type of organizational structure: a flat structure, inspired by the Spotify case study. In this scenario, leadership influence is limited, but there is a strong network of well-connected peers across the organization. This flat network forms links between nodes with a fixed probability; each node has on average eight connections, leading to a homogenous distribution of links. As a result, influence is uniformly distributed among employees throughout the network. These conditions foster a collaborative culture that is receptive to peer learning, enabling change to spread in horizontal as well as vertical directions. This type of internal setup can be seen in startups or scale-ups, where teams are closely connected, collaborative, and openly share information.

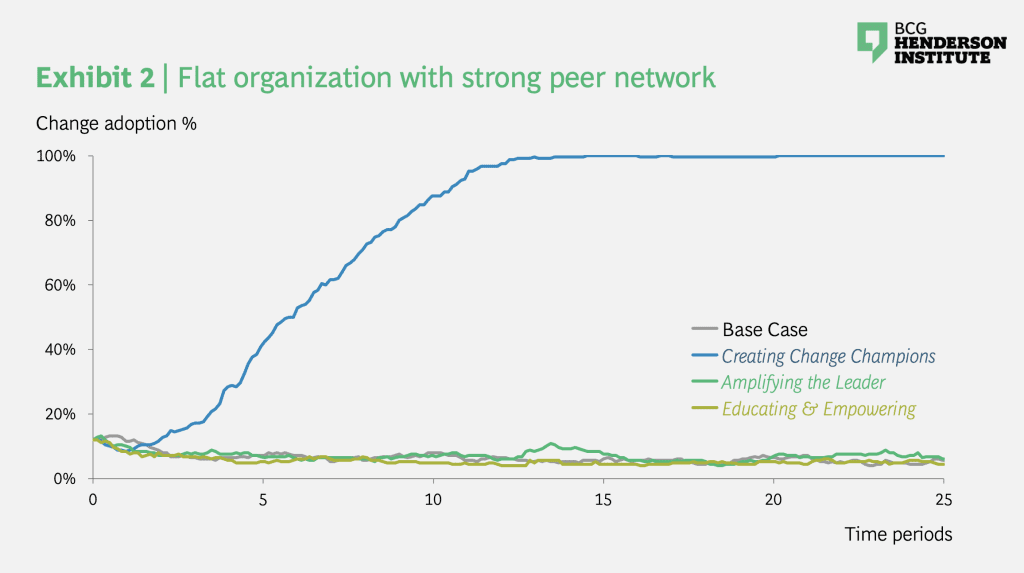

In this situation, it would be natural to rely on the established peer network and expect the change to spread out from the well-connected nodes to the whole organization. However, as demonstrated in Exhibit 2, this base case never crossed 10% in adoption. This is due to the initial adopters never reaching a critical mass sufficient to outnumber those resistant to change. Employees potentially inspired by an early change adopter still have multiple peers who have not embraced the change.

Contrariwise, the strategy of Creating change champions is consistently successful in reaching 100% adoption after 12 time periods.

This strategy uses incentives for specific employees or groups to increase their preference for change, one of the factors impacting the utility calculations. This motivates these employees to embrace the change, helping the number of adopters in the network to reach a critical mass and enabling peer influence to propagate the change throughout the organization.

Unsurprisingly, the Amplifying the leader strategy does not work in flat organizations. Without a hierarchical structure to benefit from top-down steering, the strategy relying on leadership to motivate employees never exceeded a 10% adoption rate. Similarly, the Educating and empowering strategy failed to gain traction. Employees aligned their preferences with their peers rather than focusing on their own individual performance, remaining indifferent to information about the change’s benefits.

The Creating change champions strategy proved robust, with all simulations eventually achieving ~100% adoption. Only one out of ten simulations required more than five periods for the strategy to begin taking effect. In contrast, the Amplifying the leader strategy showed more variability – while the median result of implementing this strategy plateaued at ~6% adoption, indicating its overall failure, two simulations reached 100% adoption: one after ten periods and one even sooner than the dominant Creating change champions strategy, achieving full adoption after just five periods.

This highlights the risk of choosing a less robust strategy. In a flat organization, change leaders might occasionally find success with the Amplifying the leader strategy, achieving change faster than with an approach that amplifies the peer network. The success here is very much coincidental, as the strategy achieves success only in a specific network configuration where leadership reaches the right connections at the right time. Our simulations demonstrate that this would not be a consistently effective strategy on a larger scale. When repeated, it might lead to costly failures to adopt the change.

Situation 3: Modular organization with autonomous employees

The third situation simulates an organization with highly autonomous employees, where neither leadership nor peer networks exert strong influence. In this scenario, the network of employees is loosely organized and highly heterogeneous, built by sequentially adding nodes in clusters to existing connections. These nodes are designed to be less susceptible to the influence of others, resulting in weaker and unevenly distributed influence. Such a structure can be seen at a partnership-based organization like a legal or consulting firm; in a sales team, where each account manager has distinct revenue targets for their client and ownership of the path they chose to achieve them; or in an R&D team, with researchers being granted autonomy within a larger company.

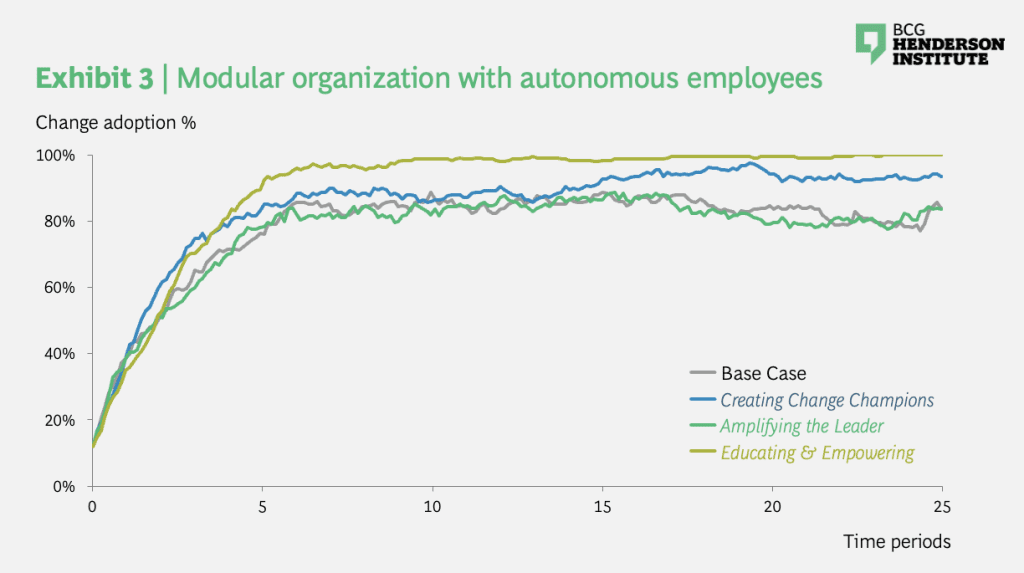

This situation proves to be highly receptive to change: the promise of a productivity boost associated with adopting a new technology is sufficient to drive significant adoption. Autonomous employees are not swayed by peer networks or leadership; their motivation to change is based primarily on perceived benefits to themselves. Since we modeled the change to positively impact performance, adoption reached an average of ~80% within five time periods.

However, without any further interventions, the organization never fully adopted the change and fluctuated between ~50% and ~100% adoption across the simulations we ran. We tested the three common strategies and found that Strategy 3: Educating and Empowering was the most successful in stabilizing the adoption and as demonstrated in Exhibit 3, resulted in ~100% change adoption within the first five to ten time periods.

The Educating and Empowering strategy relies on sharing information about the impact of change on an individual’s performance. In the model, this information influences the accuracy of the employee’s assessment of the utility of adopting the change. As more information is shared, employees can better evaluate whether the change will benefit or harm them, making them more receptive to the differences between the status quo and change adoption. By increasing the accuracy of their assessments, even slight improvements in perceived utility make employees more likely to adopt the change—as these employees are not influenced by their peers or leadership.

Relative to the base case, the other two strategies we assessed achieved only incremental improvements. The Amplifying the leader strategy reached ~84% adoption, the same as the base case. The Creating change champions strategy gradually achieved ~94% adoption, but the additional 10% increase over the baseline took about 20 time periods to manifest itself. This means that the incremental adoption gains were not due the effect of peer influence, but only to the incentives, which convinced the remaining resistant employees to change their behaviors.

Additionally, when we compare all three strategies, the Educating and Empowering strategy provides the most robust results, with only slight variation once the full adoption is achieved. Both alternative strategies result in high oscillation of the achieved adoption rates.

Implications for change leaders

Companies often do not approach change as a strategic problem, instead focusing their resources only on execution—that is, running the change program itself. This approach is frequently coupled with a reliance on change strategies that proved successful in the past—when circumstances might have been different. Our simulations demonstrated that for companies to change successfully, they must treat change as a contingent problem—matching their change strategy to the characteristics of the firm and the type of challenge encountered.

Companies need to begin by understanding their internal situation. This involves comparing themselves to their peers in the market, paying attention to characteristics, such as the strength of their peer network and leadership influence, and considering their organizational structure. It is key to assess how this situation changes throughout the organization—that is, which characteristics are consistent throughout the network versus unique to specific teams—in order to tailor and layer change strategies accordingly. For instance, the sales division may benefit from the Educating and empowering strategy due to highly autonomous sales reps, but this needs to be coordinated with the bigger organization, which might benefit from an Amplifying the leader strategy.

Once you understand your change situation, you can select the appropriate change strategy. For it to be successful, it’s crucial to ensure that your change management tactics align with the chosen strategy. Appointing the right leader to oversee the change is essential. Depending on the strategy, do you need someone to identify and motivate the right change champions within peer networks? Or do you need someone credible and experienced who can share compelling information to empower employees to accept change? Alternatively, do you need a charismatic, communicative leader with strong influence who can convince employees to adopt change?

Test different approaches, and implement pilot programs to evaluate the internal situation and its consistency across the organization. Begin the change in a single plant, specific geography, or function—such as piloting agile methodologies in R&D teams before expanding to other teams like manufacturing or marketing. Be mindful of confirmation bias: what works in one team might not work in another, if their situations differ.

Further research

Across the three situations, we observe that they vary in their inherent openness to change: in the first and third situations, the base case, indicate a high receptiveness to change, while the second situation required intervention to kick-start change adoption. This raises the question: Can companies preemptively adapt their internal characteristics to become more change-ready?

To answer this, we must consider the broader organizational context, including the costs and trade-offs of creating a change-ready environment. Leaders need to weigh the benefits of promoting autonomy and transparency versus maintaining collaborative peer networks or a clear chain of command. However, the fact that there are situations that are more receptive to change than others suggests the potential for establishing a test group within your organization, one that is highly adaptable and responsive to changes in the external world, from which the change can potentially spread out once established and tested.

In this article, we have focused on contingencies driven by internal situations, but our change simulator can also model different types of challenges. Consider well-understood and stable versus unknown and unpredictable challenges. For example, how do organizations fare when dealing with familiar challenges such as regulatory updates compared to sudden, unexpected disruptions like a global pandemic? What about repeated versus one-time challenges? Think of routine technological upgrades versus a one-off merger or acquisition. Does the frequency of the challenge impact the effectiveness of certain strategies? And our simulator allows for an even broader perspective—we can consider the stability of the challenge environment itself. Does a stable market condition require a different change strategy compared to a volatile one?

We will explore these questions and more in a future article, revealing the nuances and emerging behaviors different challenge types bring to light.