The face of migration is changing. Increasingly, migrants are traveling farther distances; they are more diverse in terms of gender, class, and origin; they have in-demand vocational skills, and they are consciously seeking cities of choice that offer opportunity and quality of life. Consider Salma, the youngest of four daughters from a family in Helwan, Egypt. A renewables systems engineer, she had considered relocating to cities where she already had relatives, such as Tokyo, Dubai, or Toronto. But in the end, after a year of working remotely for a large energy company, she moved to Berlin. Besides being an appealing, global city, the local government supported her and her employer with a fast-tracked visa process. Salma’s three young nieces in Egypt have watched her journey closely and now aspire to follow a similar path.

Our joint research reveals that migrants like Salma are becoming sought-after, not just as companies compete for talent, but also for cities engaged in an emerging competition for residents. Based on surveys of 25,000 city residents and 850 executives in 10 countries, we’ve developed five predictions for how migration will change by 2030 — and actions that policymakers should take now to prepare.

1. Migration will accelerate.

In 2022, there were nearly 40M refugees from conflict regions [1]UNHCR, “Global displacement hits another record, capping decade-long rising trend,” June 16, 2022 such as Ukraine and Syria. Yet only 280M people (3.6% of the world’s total population) live in a country other than that of their birth. Still, we believe that today’s trends point to an acceleration of migration: We expect it to move beyond 4% of the global population by 2030, or more than 350M people.

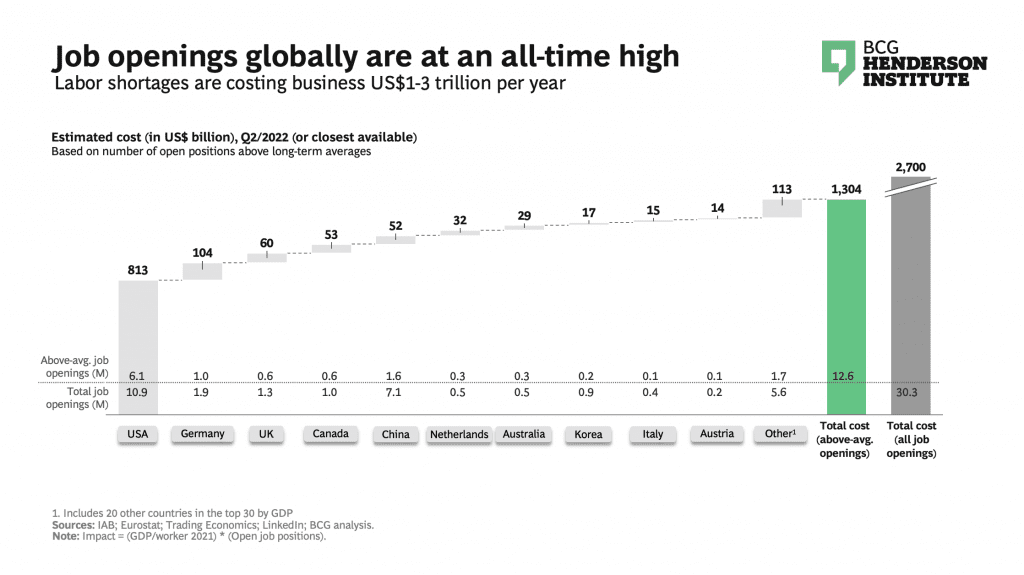

What’s driving their movement? Income gaps between cities of choice and developing countries will widen, and large parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia will see significant population increases. At the same time, as these regions make the transition to middle income economies and quality education becomes more accessible, people will emigrate [2]Center for Global Development, August 17, 2020 to seek better economic and lifestyle opportunities. Meanwhile, as of summer 2022, the world’s largest 30 economies had a record number of job openings (see Exhibit 1), especially for so-called deskless workers.[3]Dhar et al., “Why deskless workers are leaving — and how to win them back,” July 7, 2022 And for now, predictions about technology automating many manual-but-non-routine jobs in healthcare, hospitality, and construction have yet to come true — and 80% of these jobs do not require a college education. That’s significant, because currently only 25% of globally mobile workers are college-educated.[4]UN Population Division, 2021 But we expect future migrants to have both more formal education and more core and vocational skills.

2. Diversity is on the rise.

Just 30 years ago, global migration was not very global: In 1990, 45% of migration took place between neighboring countries, and 23% took place between countries tied to a common colonial history. Today, only 27% and 17% of migration occurs along these geographical or historical lines, respectively. Instead, migrants are more deliberate about their choices and tend to cover greater distances (+100 km on average). Also in 1990, 50% of all migrants came from just 14 countries, but that share has now nearly doubled to 27 countries.[5]BCG Analysis based on World Bank, UN Population Division data

Women and girls have always made up close to half of all international migrants (48% in 2020). Now, female migrants from the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia are on the rise, which both reflects and drives changes in gender norms that increasingly allow women in traditional societies to travel more independently.[6]Migration Data Portal Looking ahead, we predict a majority of migrants will be women. Migrant women also make a substantial economic contribution, as they are much more likely to work outside of them home (64%) than those who do not migrate (~48%).[7]UN Women, “How migration is a gender equality issue”

3. Migration will become (even) more city-to-city.

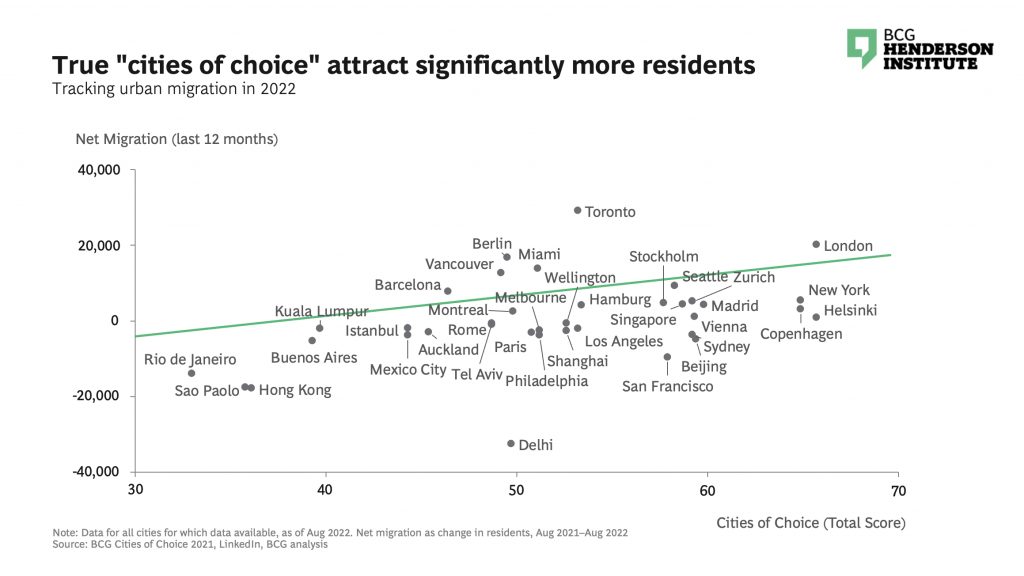

As the increasingly powerful centers of every national economy, cities naturally attract the lion’s share of migrants (see Exhibit 2). In large cities, more than 50% of residents will have moved during their lifetime, and this number will only increase.[8]BCG analysis based on Cities of Choice, 2021 And as global firms increasingly adopt English as the universal language of business, people tend to work in digital or office environments that are more rooted in a common business culture versus a uniquely national one. This isn’t limited to mega-corporations; many tech startups are hiring globally from Day 1. This makes it easier to cross borders to pursue opportunities, wherever they may be.

When these workers are deciding where to move, livability trumps almost everything (except salary). A recent BCG survey of digital workers who have migrated to eleven global cities revealed that having a high standard of living was far and away the most important determinant in choosing where to move, at 66% — far higher than the 15% who were influenced by a similar culture and the 7% who sought a community of the same ethnicity.

4. In the long run, necessity will trump nationalism.

Rather than moving toward a less globalized, more nationalistic future — in which migrants are viewed as a harbinger of unwelcome change — we predict that, despite considerable political polarization on the issue in some countries, the world will continue to open to global migrants. This will not be about goodwill, but rather sheer necessity.

For university-educated migrants, the world is already more open than ever, as a recent BCG analysis has shown.[9]Johann Harnoss, Anna Schwarz, and Martin Reeves, “Building a Globally Diverse Team Is Actually Getting Easier,” Harvard Business Review, January 24, 2022. But we expect the relative freedom of movement for highly skilled people will increasingly also be given to those with much needed vocational skills in trade crafts, logistics, and healthcare — due to the dramatic need for such workers, especially in surging megacities.[10]Germany, until recently a country that decidedly did not see itself a country of immigrants, is already moving in this direction, both through the planned opportunity card, a points-based work visa … Continue reading Attitudes toward immigration are also shifting, as younger generations tend to be significantly more socially liberal in many respects.

5. The war for talent will become a war for residents.

In the past, cities focused on attracting and retaining businesses that would provide employment to the local population and drive economic growth. But this logic is being flipped on its head. As migration accelerates and work is decoupled from place, cities must recruit for the economy they want, not the economy they have. This is especially urgent because, as people become more mobile, they will carry their tax revenues with them — which could wreak havoc on a city’s finances if too many people leave too quickly.

Moreover, the winner-takes-all dynamics at play in cities create a powerful pull of talent into a small handful of highly successful locales. This means that other cities become talent donors — staging grounds that young people eventually leave, often for good. Fertility rates are also lower in cities, meaning that without inward migration, populations will naturally decline by up to 50% by the end of the century. In advanced economies where urbanization is already high, this will mean attracting migrants from cities seeking to “trade up.” Cities in developing countries, particularly in African countries with very large populations of young people, have the opposite problem, for now. But all cities, from Dallas to Dar es Salaam, must make broad improvements to retain their residents or risk them seeking prosperity elsewhere.

Implications for government leaders.

If the predictions above are realized, it will have major implications for leaders of both national governments and cities.

National government officials will need to:

- Devise and implement a proactive migration strategy. They’ll need to restructure immigrant visa, labor, and work regulations that still follow a logic of domestic labor market protection, with a particular focus on coherence and transparency. Doing so would not just remove many practical roadblocks and uncertainties for immigrants and hiring firms, but also serve as a marketing tool. For example, even many years after its original introduction, the Canadian points-based system continues to be a strong pull factor thanks to its relative simplicity.

- Design policies that both drive economic growth and innovation and ensure support from voters. Research shows that voters support migration if there is transparency around rules and a sense of control over who is admitted under which criteria. In addition, migrant diversity matters. Policies that encourage a healthy diversity of immigrant inflows can foster faster integration into the host society and thus build stronger public support.[11]Alberto Alesina, Johann Harnoss, and Hillel Rapoport, “Birthplace Diversity and Economic Prosperity,” Journal of Economic Growth volume 21, pages 101–138 (2016)

- Build an ecosystem of partners. Based on a strategic forecast of future labor market needs, public leaders in countries that are projected to be demographically challenged should identify key partner countries that are projected to grow their populations much faster, such as Egypt, Nigeria, Indonesia, and Algeria, and create bilateral partnerships that combine education with targeted legal and safe migration pathways into high-need jobs.

City government leaders will need to:

- Lead through superior administrative processes. City officials can nudge national policy makers towards more effective migration strategies that benefit all: cities, their local inhabitants, and global newcomers. In addition, they have many local administrative levers they can pull, for example, fast-tracking processes (like the example of Berlin above) or partnering with the private and NGO sectors to create talent markets that reward recruitment agencies and training providers to successfully attract of top talent.

- Establish a strong global brand among talent communities, including university and high school students globally. While many cities, such as Edinburgh, Barcelona, and Singapore, succeed in building a brand for education, not all cities manage to keep their students after graduation — often due to a lack of suitable jobs, but also due to visa barriers requiring talent to leave the country. Voucher-based models that currently work well in the labor market to integrate the long-term unemployed could be extended into retention of global migrants once they complete their education.

- Focus on livability for all residents, prioritizing affordable housing, access to quality education, mobility, medical care, entertainment options, and social and green spaces. These may feel like traditional levers, but there is plenty of room for innovation, for example, through digital and metaverse learning solutions like immersive STEM courses in virtual reality that provide rich content and vastly expand access. Most importantly, make residents a part of the solution, to source the best ideas and secure buy-in from the start.

The time to act is now: We predict that the pillars of the global economy will coalesce around nations and cities that deliberately guide policy toward attracting and retaining top talent.