This article is the fourth in a series of publications offering practical guidance on business ecosystems. The first article addressed the question, “Do you need a business ecosystem?” The second reflected on, “How do you ‘design’ a business ecosystem?” And the third dealt with the question, “Why do most business ecosystems fail?”

It is widely acknowledged that business ecosystems offer great potential. Compared to more traditional ways to organize businesses, such as vertically integrated companies or hierarchical supply chains, business ecosystems are praised for their ability to foster innovation, scale fast, and adapt flexibly to changing environments.

However, many companies that try to build their own ecosystem struggle to realize this potential. Our past research has shown that fewer than 15 percent of business ecosystems are sustainable in the long run,[1]M. Reeves, H. Lotan, J. Legrand and M. Jacobides, “How Business Ecosystems Rise (and Often Fall)”, MIT Sloan Management Review, July 30, 2019, … Continue reading and that the most prevalent reason for failure are weaknesses in the governance model — the way the ecosystem is managed.[2]U. Pidun, M. Reeves and M. Schuessler, “Why do most business ecosystems fail?”, Boston Consulting Group, June 2020, bcg.com/publications/2020/why-do-most-business-ecosystems-fail

Governance failures of business ecosystems

Business ecosystems are prone to different types of governance failures. Many ecosystems struggle because they choose a too open governance model. For example, Shuddle launched in 2014 with the ambition to become the Uber for kids. The company offered a rather open access to its platform and did not subject its drivers to fingerprints background checks, in contrast to its more successful competitor HopSkipDrive that was convinced that such checks are required if children are involved. As a result of its open governance model, Shuddle not only faced security concerns but also found it difficult to ensure the required service quality. It had to shut down in 2016.[3]S. Lacy, “Sources: Shuddle’s collapse was the fault of Shuddle, not the investment climate”, Pando, April 19, 2016, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading

Other ecosystems fail due to a too closed governance model. For example, when the iPhone was launched in 2007, the BlackBerry was still widely considered a superior smartphone for corporate users — in terms of data security, its keypad, and battery life. RIM, the company behind the BlackBerry, also understood that it needed to follow an ecosystem approach to the development of applications for its device. However, with the aim to maintain its high data security standards, the company chose a rather closed governance model, restricting incentives for app developers to join the platform. As a consequence, the BlackBerry lost ground to the smartphone ecosystems based on iOS or Android and became a niche product.

Some business ecosystems struggle because they cannot control bad behavior on their platform. For example, many restaurant booking platforms suffer from large numbers of “no show” reservations that alienate their restaurant partners. OpenTable addressed this challenge by introducing a policy that required diners to cancel reservations they made through the platform at least thirty minutes in advance, banning users who failed to follow this policy four times within a twelve-month period.[4]J. Phillips, “OpenTable launches new campaign to combat reservation no-shows”, SFGATE, March 21, 2017, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading

Another type of governance failure are conflicts among partners of an ecosystem, in particular between the orchestrator and its complementors. Early warning signs may be complaints of complementors about the orchestrator exploiting its dominant position and imposing unfair terms and conditions on the ecosystem. For example, Amazon was accused of using sales data from third-party merchants on its marketplace to identify attractive market segments and enter them with its own brands.[5]K. Cox, “Antitrust 101: Why everyone is probing Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google”, Ars Technica, November 5, 2019, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading Similarly, Epic Games, the developer of the popular video game Fortnite, recently filed antitrust lawsuits against Apple and Google, accusing both companies to misuse their dominant position in mobile operating systems by requiring that payments for in-app digital content be processed via their app-stores’ respective internal billing systems.[6]The Verge, “Fortnite vs. Apple and Google: everything you need to know about Epic’s mobile app stores fight”, The Verge, continuously updated summary, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading

Some business ecosystems experience backlash from consumers or regulators, indicating weaknesses in their existing governance that may threaten their license to operate. For example, social networks are harshly criticized for their data privacy policies and for disseminating false or misleading information on their platforms. Ride-hailing and lodging marketplaces are accused of circumventing regulation in the transportation and hospitality sector in order to avoid costly requirements for safety, insurance, hygiene, and workers’ rights.

Finally, an extreme case of governance failure are legal actions against the platform or its ecosystem. For example, Backpage.com, a classified ad website, did not restrict the types of ads it would accept, leading to many solicitations for illegal activities. This led to at least eight lawsuits between 2011 and 2016. Backpage won each of these lawsuits, but the website was eventually seized as part of an investigation by federal law enforcement agencies.[7]L. Jarrett and S.A. O’Brien, “Justice Department seizes classified ads website Backpage.com,” CNN, April 7, 2018, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading

Objectives and challenges of ecosystem governance

Getting the governance of your ecosystem right is thus a major success factor and a big challenge. Orchestrators must establish an effective governance model, which we define as the set of (explicit or implicit) structures, rules and practices that frame and govern the behavior and interplay of participants in a business ecosystem.

Many orchestrators struggle with this challenge because managing an ecosystem is very different from managing an integrated company or a vertical supply chain. Ecosystems are built on voluntary collaboration between independent entities, rather than clearly defined customer-supplier relationships and transactional contracts. Instead of exerting hierarchical control, the orchestrator must convince partners to join and collaborate in the ecosystem. This challenge is further aggravated by the dynamic nature of the ecosystem model. Most business ecosystems develop very fast, they continually add new products and services, connect new members and change roles and interactions, posing high requirements on the flexibility and adaptability of the governance model.

In some ways, the governance of an ecosystem can be compared to the governance of a market economy. The role of the orchestrator is not to manage but to enable the other players, and to act as the steward of the ecosystem. The governance model is needed to avoid market failures and must pursue three objectives:

- First, ecosystem governance should support value creation of the ecosystem. To this end, the governance model must facilitate recruiting, motivating and retaining partners; align partners’ interests, strategies and actions; and optimize resource allocation across partners.

- Second, ecosystem governance should manage risk in the ecosystem. To this end, the governance model must ensure that all partners comply with (local) laws and norms; protect the reputation of the ecosystem; ensure its social acceptance to avoid backlash by consumers, incumbents or regulators; and minimize all other kinds of negative externalities.

- Third, ecosystem governance should optimize value distribution among ecosystem partners. To this end, the governance model needs to establish a fair way to share the value that is created by the ecosystem and ensure that all required partners can earn a decent profit and that partners are compensated in accordance with the value they add to the system.

A framework for ecosystem governance

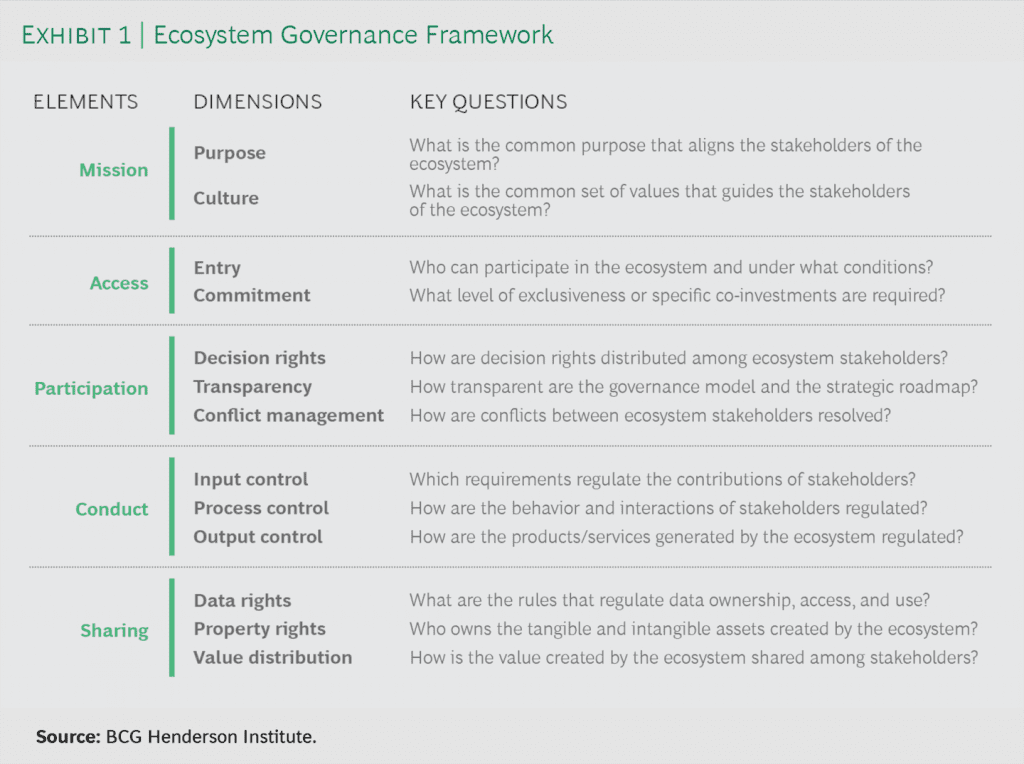

How can the orchestrator and partners of an ecosystem develop a governance model that best achieves the above objectives? Based on our analysis of the governance of more than 80 business ecosystems from different domains, we have developed a comprehensive framework of ecosystem governance (exhibit 1). The framework covers the five main building blocks that must be addressed and can be used to manage a business ecosystem:

- Mission: What are the common purpose and culture that guide and align the stakeholders of the ecosystem?

- Access: Who is allowed to enter the ecosystem, and what level of commitment in terms of exclusiveness and/or specific co-investments is required?

- Participation: How are decision rights distributed among ecosystem stakeholders, how transparent are the governance model and strategic roadmap, and how are conflicts resolved?

- Conduct: How is the behavior of stakeholders of the ecosystem regulated by controlling the input they provide, the process they need to follow, and the output they generate?

- Sharing: What are the rules that regulate data rights and other property rights, and how is the value created by the ecosystem distributed among stakeholders?

To elucidate how the governance model of a business ecosystem can be systematically designed, we will now discuss the five building blocks of ecosystem governance in more detail, explain the choices for each dimension, and illustrate them with examples.

Mission

Partners in a business ecosystem can be aligned by a common mission that is expressed as a connecting sense of purpose or a joint set of values and culture.

Purpose can be a strong motivation for joining and contributing to an ecosystem. It typically relates to a major problem that can be solved through the ecosystem, a big goal that is to be achieved, or an important contribution to society. For example, Kiva, the non-profit crowd-funding platform operating across 76 countries, aligns partners behind its purpose to “expand financial access to help underserved communities thrive”. The ecosystem wants to create a “financially inclusive world where all people hold the power to improve their lives” and contribute to society because, “through Kiva’s work, students can pay for tuition, women can start businesses, farmers are able to invest in equipment and families can afford needed emergency care”.[8]Kiva, “About: We envision a financially inclusive world where all people hold the power to improve their lives”, Kiva.org, accessed 15.12.2020, kiva.org/about

A strong culture can also be an important glue to align partners in an ecosystem. Sometimes the culture is codified in a defining set of values, as in the case of Wikipedia and its five fundamental principles that state that Wikipedia (1) is an encyclopedia (not an advertising platform), (2) is written from a neutral point of view, (3) is free content that anyone can use, edit, and distribute, (4) has editors that should treat each other with respect and civility, and (5) has no firm rules.[9]Wikipedia, “Wikipedia: Five pillars”, Wikipedia.org, November 28, 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Five_pillars In other ecosystems culture is tacit but not less strong, as in the case of TopCoder, the global talent network and crowdsourcing platform connecting more than a million designers, developers, data scientists, and testers with corporate clients. TopCoder rests on the coder communities’ values of, for example, “intrinsic motivations for doing the work or learning from the work, career concerns, status and recognition in the community or simple affiliation with the community”.[10]K. J. Boudreau and A. Hagiu, “Platform Rules: Multi-Sided Platforms As Regulators”, in Platforms, Markets and Innovation, edited by Annabelle Gawer, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2009

Admittedly, some commercial business ecosystems are mainly driven by financial objectives and lack a strong culture. But if you can identify a compelling purpose for your ecosystem and establish a positive culture early in its development, this can be a very potent instrument of attracting and retaining the right partners and encouraging the right behavior in your ecosystem without having to regulate every detail with complex rules and written standards.

Access

Controlling access can be an effective way to manage an ecosystem because it not only establishes who can participate in the ecosystem under which conditions, but also what level of commitment is required in the form of exclusivity agreements and ecosystem-specific co-investments. Such access rules must be defined for partners and suppliers to the ecosystem as well as for its customers and users.

On the supply side, many ecosystems are very open and have no restrictions for participation, such as most online marketplaces that are open to all sellers. Some platforms restrict entry by segmentation, such as OpenTable, the restaurant booking platform that recruited mainly restaurants from specific areas in selected cities as part of its launch strategy.[11]D. Evans and R. Schmalensee, “Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms”, Harvard Business Review Press, 2016, page 11 Others restrict participation based on qualification. For example, many gig economy ecosystems like Belay Solutions only allow qualified suppliers on their platform.[12]Belay Solutions, “Work with us”, belaysolutions.com, 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, belaysolutions.com/work-with-us/ Some orchestrators follow more closed approaches and establish a staged entry model, such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) that segments its partner network into consulting partners and technology partners, or even handpick ecosystem partners on a case-by-case basis, such as Climate Corp for its FieldView smart-farming platform.[13]E. Cosgrove, “Checking in With Climate Corp’s Open Platform Strategy and the Future of Ag Data”, agfundersnews.com, January 30, 2018, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading

On the demand side, most ecosystems don’t limit participation. If restrictions exist, they are mainly driven by the scope of the product and service offering. For example, the B2B marketplace Covisint deliberately focused on the automotive industry. Similarly, car-sharing platforms such as getaround only address car drivers and require confirmation of a driver license for participation. Staged entry and freemium models are also common on the demand side, such as on the Amazon marketplace where entry is free for all customers, but premium services and offerings are available only for subscribers to ‘Amazon Prime’.

Another way to control access is to ask for a certain level of ecosystem-specific co-investments to enhance commitment to the ecosystem. As expected, this governance instrument is more common on the supply side. Some platforms simply try to achieve this commitment by demanding an access fee. For example, Google and Apple both charge app developers a one-time or annual fee to access their application programming interfaces (APIs). Some orchestrators require partners to invest into ecosystem-specific assets. For example, Apple initially demanded its smart-home partners to purchase Apple’s Mfi (Made for iPod/iPhone/iPad) chips and include it in their hardware.[14]R. Crist, “What a streamlined HomeKit means for Apple’s smart home ambitions”, CNET.com, July 21, 2018, accessed 15.12.2020, cnet.com/news/apple-homekit-software-authentication-explained/ And other platforms encourage the development of ecosystem-specific capabilities. For example, SAP offers four ‘partner levels’. To move up, partners can earn ‘value points’ for contributions and investments.[15] SAP, “SAP® PartnerEdge®Program Guide for Software Solution and Technology Partners”, SAP, 2014 On the demand side, such co-investment requirements are less common and typically have the form of an access fee or the need to buy platform-specific equipment, for instance, a console for a video-gaming platform.

Finally, orchestrators can link access to the ecosystem with incentives or requirements for exclusiveness, demanding from their partners not to offer their products or services on competing platforms. While exclusiveness may be desirable, for most ecosystems it is not feasible. For example, most transaction ecosystems, such as marketplaces or booking and rental platforms, don’t demand exclusivity from their suppliers, and even less from their users. Some platforms establish incentives for exclusive use, in the form of monetary rewards, additional services or privileged information. For example, Amazon Fulfillment Services charges suppliers higher fees for orders not placed via the Amazon marketplace.[16]F. Zhu and M. Iansiti, “Why Some Platforms Thrive and Others Don’t”, Harvard Business Review, January, 2019, page 8 Lyft operates driver centers with discounted services to incentivize exclusiveness,[17]Lyft, “Lyft Driver Services: High quality, fairly-priced vehicle services”, lyft.com, 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, lyft.com/driver/vehicle-service and drivers can rent a vehicle for a weekly fee via Lyft’s ExpressDriver program if they agree to facilitate 20 Lyft rides per week; ExpressDrive rentals cannot be used for any other ‘for-hire’ services.[18]Lyft, “Help Center: Express Driver overview”, lyft.com, 2018, accessed 15.12.2020, help.lyft.com/hc/en-us/articles/115013080108 Finally, some platforms even negotiate exclusivity contracts with specific suppliers, such as the Blu-ray consortium did with leading film studios to beat the competing HD-DVD format and more recently Spotify does with individual podcast providers.

Participation

Once partners are admitted to an ecosystem, the next governance question relates to the degree of their participation in its development. Participation is reflected in the distribution of decision rights, transparency and conflict management.

A small number of ecosystems opt for joint decision making and establish institutions and processes to share the authority and responsibility for the governance and strategic roadmap of the ecosystem. For example, the open-source operating system Linux is managed by a committee consisting of members of the Linux community, including corporate members, individual open-source leaders, vendors, users, and distributors.[19]The Linux Foundation, “About: Board Members”, linuxfoundation.org, 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, linuxfoundation.org/about/board-members/ Similarly, Wikipedia is governed by a structure of committees whose members are elected by the community and that make decisions by consensus.[20]Wikipedia, “Wikipedia: Administration”, November 3, 2020, Wikipedia.org, accessed 15.12.2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Administration At the other end of the spectrum, the orchestrators of most transaction ecosystems claim a central authority for deciding about the governance and strategic roadmap of the platform. For example, Uber and Airbnb both decide centrally which offerings to include on the platform, while ecosystem partners (drivers and lessors) are restricted to providing the service. Most solution ecosystems select an intermediate option with largely decentral decision making that is guided by the orchestrator. For example, in many smart-home ecosystems, complementors decide independently about their offering and strategic roadmap, while the orchestrator defines the overall governance.

Participation requires transparency, and we observe a wide range of practices. Some ecosystems are largely transparent, even to non-members. For example, Dassault Systèmes (DS) shares a clear innovation roadmap for its product lifecycle management (PLM) ecosystem, laying out the target industries and planned solutions as well as the role DS wants to play.[21]A. De Meyer and P. J. Williamson, “Ecosystem Edge: Sustaining Competitiveness in the Face of Disruption”, Stanford Business Books, 2020, page 93 Other ecosystems are largely transparent, but only to members. For example, complementors on Apple’s smart-home platform HomeKit need to sign a non-disclosure agreement when joining and before receiving detailed information about governance-related questions such as Apple’s royalties.[22]Apple, “Frequently Asked Questions: What is the royalty associated with MFi accessories?”, Apple.com, 2002, accessed 15.12.2020, mfi.apple.com/faqs#qa7; Apple, “MFi Program Enrollment”, … Continue reading The majority of ecosystems we investigated, however, are mostly intransparent. This can be either because they follow a rainforest model, such as Google and Apple that cannot provide much transparency about the future development of their mobile platforms due to the independent, decentralized development of apps and the (deliberate) lack of a coordinated strategic roadmap. Or they follow a walled-garden model, such as Uber and Airbnb that don’t want to disclose how they will develop their platforms, which verticals they are going to join, and which additional services partners are invited to offer in the future.

The final governance question related to participation is how conflicts between ecosystem stakeholders are resolved. Some ecosystems have no or only limited internal regulations for conflict management and rely on outside jurisdiction. Many emerging platforms have no defined processes and use the orchestrator as arbiter. For example, most social media platforms start with only limited guidelines for conflict resolution and have to decide on a case-by-case basis which content to take down. When clear processes are in place, we observe two models. In some ecosystems, conflicts are centrally managed by the orchestrator, as in the case of Uber where riders and drivers can complain about each other via the Uber app and the conflict is resolved by a dedicated central team. In other ecosystems, stakeholders are more strongly involved in conflict resolution. For example, community platforms such as Craigslist and Reddit use volunteering and professional moderators to solve conflicts, and Alibaba even established a ‘market judgement committee’ for its Taobao platform to regulate product classification, with members being selected among qualified buyers and sellers and decisions made by voting.[23]A. De Meyer and P. J. Williamson, “Ecosystem Edge: Sustaining Competitiveness in the Face of Disruption”, Stanford Business Books, 2020, page 115

Conduct

Most orchestrators don’t want to manage their ecosystems by only relying on a strong mission, access rules and regulations for participation, they want to directly influence stakeholder behavior. They can choose among three approaches: input, process and output control.

Input control specifies the requirements for the partners’ contributions to the ecosystem. Some ecosystems, such as most social platforms, have no or only limited input standards. For example, Twitter’s restriction of posts to a length of 280 characters is only a weak form of input control. Most digital solution ecosystems go one step further and control input through prescribed interfaces that specify input formats and technical interactions through APIs (application programming interfaces), SDKs (software development kits) and IDEs (integrated development environments). Other ecosystems have established standards and instruments for quality control for new contributions. For example, Apple deploys extensive quality checks on newly developed apps before approving them for the platform. And finally, some orchestrators claim the right to handpick and curate input on their platform. New applications on John Deere’s smart-farming platform, for instance, must be individually approved and need a separate license agreement.[24]John Deere, “Moving your application to Production”, Deere.com, 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, developer-portal.deere.com/#/startDeveloping/%2Fhelp%2Fgetstarted%2FGoToProduction.htm The online gaming platform Steam initially also curated new games in its ecosystem, first by handpicking them centrally and then by letting users vote which games to include (‘Steam Greenlight’), but later restricted itself to quality control by only reviewing game configurations and checking for malicious content (‘Steam Direct’).[25]J. Matulef, “Greenlight gets the red light: Steam Greenlight to be replaced with Steam Direct next week”, Eurogamer, June 6, 2017, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading

In process control, the orchestrator tries to regulate the behavior of partners as they interact with each other and with the platform. Again, many social platforms are examples of ecosystems with no or only limited process control. For example, Craigslist only provides an open interface for communication and matching, while the process of resulting transactions and their fulfillment is not regulated. At the other end of the spectrum, some ecosystems stipulate end-to-end regulation of the process. For example, Kiva centrally defines every step on its micro-finance platform, from loan application to underwriting, approval, posting, fundraising, disbursal, and re-payment.[26]Kiva, “The journey of a Kiva loan”, kiva.org, 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, kiva.org/about/how Uber even prescribes the routes that drivers are supposed to take. Other ecosystems establish partial regulation of the process, such as Apple that uses the AppStore as a control point for the distribution and purchase of apps. And lastly, some orchestrators try to softly govern behavior on their platform by offering process support with central services. For instance, software ecosystems such as SAP and AWS provide forums, services and trainings to help partners develop new applications and improve the scope and quality of the offering.

Finally, output control directly regulates the quality of products and services created by the ecosystem. Only few platforms deliberately apply no or only limited output control. For example, Doctolib, an online booking platform matching doctors and patients, explicitly refrains from evaluating doctors because objective measures are difficult to apply in healthcare.[27]M. Kroker, “Doctolib füllt eine Lücke für Patienten und Praxen“ [English: “Doctolib fills a gap for patients and practices”], Wirtschaftswoche, June 22, 2019, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading The most frequent mechanism for output control in transaction ecosystems is customer feedback. It can be just used for transparency, as with most app store ratings or customer reviews on marketplaces or booking platforms, but it can also be used to exclude partners with evaluations below a certain threshold, as in the case of Airbnb and Uber. A more active instrument for regulating output is editorial control. It can be accomplished by the orchestrator, as in the case of Facebook and Twitter that established substantial internal units for content curation, but also by qualified users. For example, the online gaming platform Steam appoints users as ‘curators’ who review games and connect with developers on ‘curator connect’, and ‘explorers’ who look for ‘fake games’.[28]Steam, “Curators and Curator Connect”, Steamworks, 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, partner.steamgames.com/doc/marketing/curators, [29]R. McCormick, “Valve admits Steam has a ‘fake game’ problem: New system will ask Steam Explorers to find hidden gems”, The Verge, April 4, 2017, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading And lastly, some platforms use AI-based algorithmic control to curate output. On the TopCoder platform, for instance, code submitted in competitive programming matches is automatically assessed by algorithms, and the results are used for rating and ranking developers.[30]Topcoder, “How to Compete in SRMs”, Topcoder.com, 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, topcoder.com/community/competitive-programming/how-to-compete

Sharing

The final building block of ecosystem governance regulates data rights, property rights and how the value that is created by the ecosystem is shared among partners.

The regulation of data rights needs to address the ownership, access and use of data in the ecosystem.[31]M. Russo and T. Feng, “How far can your data go?”, Boston Consulting Group, September 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, bcg.com/publications/2020/exploring-the-alternative-data-use-landscape. We observe four basic models: (1) Data is owned and shared by the creator. The owner of the data can decide to share data case by case, only with the orchestrator (as complementors of the Apple HomeKit) or more broadly with other partners in the ecosystem (for example, in Germany, patients decide on an individual basis which parties they grant access to their electronic health records[32]Gematik, “Die Elektronische Gesundheitsakte (ePA)“ [English: „The Electronic Health Record (EHR)“], Gematik, 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, gematik.de/anwendungen/e-patientenakte/). (2) Data is owned and used by all partners, as in the case of Tracr, an end-to-end blockchain-based diamond-tracing platform. While this model is still rare today, we expect it to become more common with the further advancement and spread of blockchain technology. (3) Data is owned and shared by the orchestrator. For example, Alibaba owns transaction data on its marketplaces but voluntarily shares information on demand patterns with its merchants, encouraging them to invest in advanced data analytics. (4) Data is owned and used by the orchestrator. Some platform orchestrators, such as Uber and Lyft, own all transaction data generated on their platform and decide not to share them with their partners.

The regulation of property rights of the (in)tangible assets that are created by the ecosystem faces similar challenges. In rare cases, there are explicitly no intellectual property rights derived from the ecosystem activity. For example, contributors to Wikipedia agree to waive all property rights and release their contribution under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license.[33]Wikipedia, “Wikipedia:FAQ/Overview — Who owns the encyclopedia articles?”, Wikipedia.org, November 8, 2020, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading In most solution ecosystems, however, intellectual property is owned and used by the creator. For instance, developers and complementors in the Linux ecosystem own the intellectual property of their Linux versions (e.g. RedHat) or solutions built with Linux. Occasionally, property rights are partially limited by the orchestrator, as in the case of SAP that offers ‘timed’ property rights for partner applications and provides an ecosystem roadmap for the next two years, laying out which (existing) products will be integrated in SAP’s core platform.[34]G. Parker and M. Van Alstyne, “Innovation, Openness and Platform Control” Management Science, August 11, 2017 Lastly, in some ecosystems, such as ride-hailing or food-delivery platforms, intellectual property is developed, owned and used mainly by the orchestrator.

When it comes to value distribution, many ecosystems follow a strict market-based approach and encourage independent pricing by ecosystem members. For example, on the Apple and Android mobile platforms, the orchestrator sets a take rate and developers are free to set prices for their applications. TopCoder has established an inverse market mechanism, where corporate clients set the price they are ready to pay, and developers compete for the project.[35]M. Morris, “Crowdsourcing: The Future of an Efficient On-Demand Economy”, Topcoder.com, March 18, 2019, accessed 15.12.2020, topcoder.com/crowdsourcing-on-demand-economy/ Some solution ecosystems try to optimize value capture for their platform by coordinating pricing and negotiating value distribution. Many video game console platforms, for instance, subsidize hardware with game sales. Climate FieldView sets package prices for its smart-farming offering and individually negotiates value distribution with its partners and suppliers.[36]E. Cosgrove, “Checking in With Climate Corp’s Open Platform Strategy and the Future of Ag Data”, AgFunderNews, January 30, 2018, accessed 15.12.2020, … Continue reading Finally, some ecosystems apply central pricing and value distribution, letting partners only decide to accept or leave. For example, ride-hailing platforms Uber and Lyft use central algorithmic pricing schemes, and content providers on media and entertainment platforms such as Youtube, Medium or Spotify receive a share of value based on the engagement level of users.

How to select the right governance model

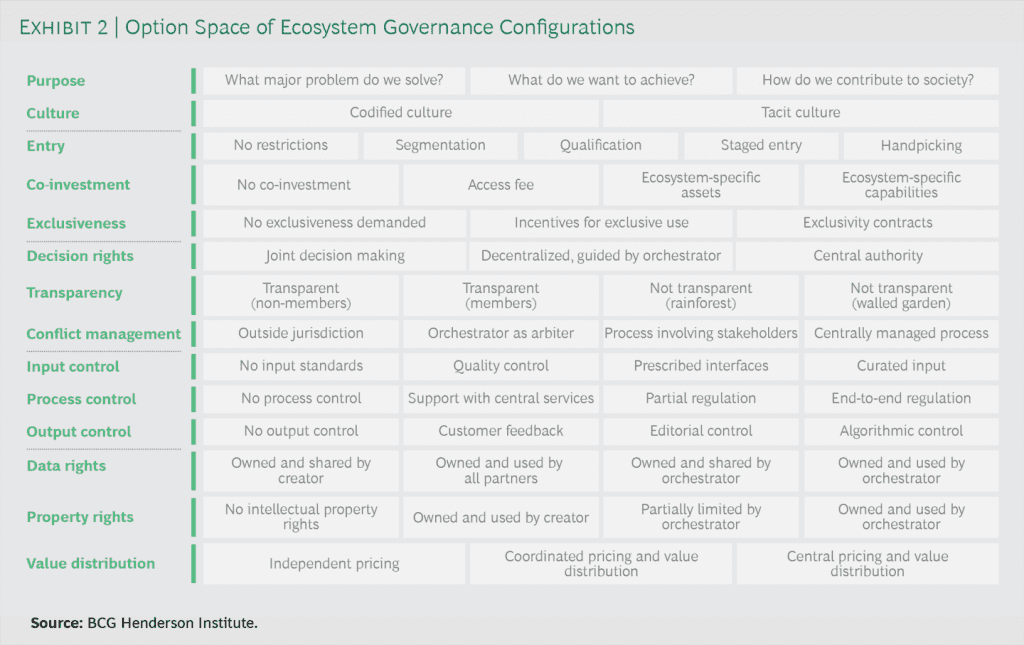

Given the many essential elements of ecosystem governance, and the many options for each element (exhibit 2), how can you select the best governance model for your ecosystem?

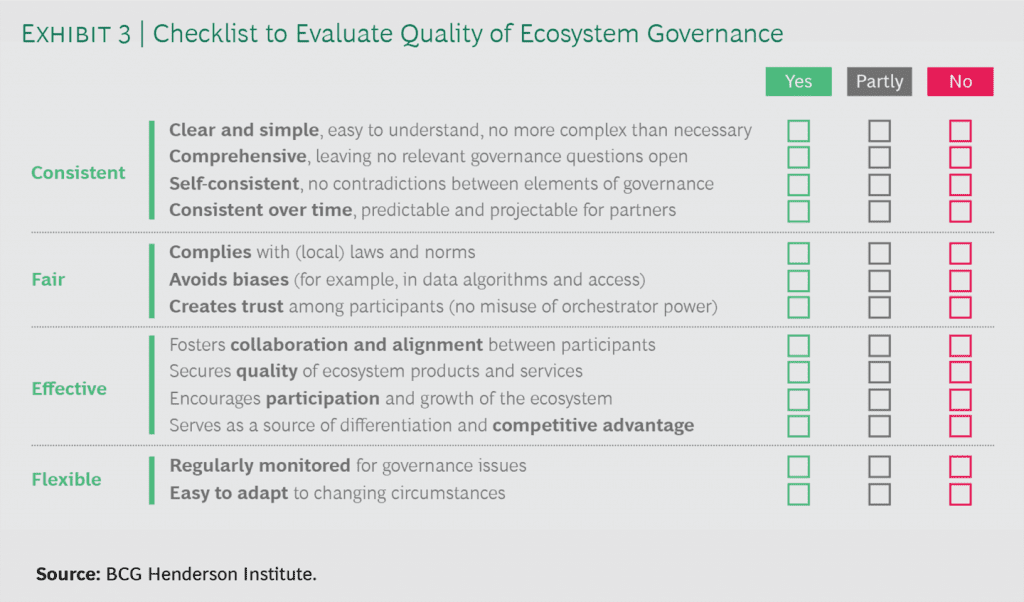

For starters, there are some general characteristics of good ecosystem governance (exhibit 3):

- Consistency: The governance model should be clear and simple, not more complex than necessary, and easy to understand for all stakeholders. At the same time, it should be comprehensive and address all relevant governance questions. In addition, the individual elements of governance should be self-consistent, free of contradictions, and also consistent over time to provide a predictable framework to all partners.

- Fairness: Good ecosystem governance needs to ensure fair and trusting dealings with all stakeholders. In particular, it should be compliant with (local) laws and norms and avoid inappropriate biases, for example, in data algorithms and access. Overall, the governance model should create trust among partners and, in particular, inhibit the misuse of orchestrator power.

- Effectiveness: In order to be effective, the governance model should foster collaboration and alignment between participants, secure the quality of the ecosystem’s products and services, and encourage participation and growth of the ecosystem. In this way, effective governance can become a source of differentiation and competitive advantage for the ecosystem.

- Flexibility: Finally, ecosystem governance must be regularly monitored. Instruments and early-warning indicators for emerging governance issues should be in place, and the governance model should be flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances and new challenges.

Besides these general characteristics of good ecosystem governance, ecosystem-specific criteria play a role in selecting the right governance model. For example, we find that many successful transaction ecosystems opt for a rather open access model with only limited requirements regarding the commitment of partners. Decision rights are mainly owned by the platform orchestrator, and data sharing is limited. Behavior on the platform is tightly regulated based on standard terms and conditions and sophisticated instruments for input, process and output control. In contrast, many successful solution ecosystems that we investigated are more selective in granting access to the ecosystem. They are more frequently aligned by a common purpose and set of values and require a higher level of commitment in the form of ecosystem-specific investments or capabilities. In exchange, solution ecosystems give partners more decision rights, share data more broadly, and curtail the behavior in the ecosystem less strictly.

More generally, the right governance model also depends on the strategic priorities of the ecosystem. If the focus is on fast growth, flexibility, decentral innovation, exploration and value creation, the governance model should be rather open and follow the rainforest paradigm of diversity, autonomous creativity and adaptability, as exemplified by Alibaba’s Taobao marketplace or the Android mobile operating system. If, on the other hand, the focus is on quality, commitment, coordinated innovation, exploitation and value capture, the governance model should be rather closed and follow the walled-garden paradigm of consistency, alignment and control, as exemplified by many B2B platforms such as smart farming or smart mining.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that ecosystem governance is not static but must be actively developed over time. The initial governance model can be tailored to the early set of ecosystem partners, but the orchestrator must make sure that the model is scalable and doesn’t become too complex as the ecosystem grows. The development of an ecosystem is strongly path dependent, and many successful platforms start with a rather closed approach to establish the right quality and behavior, which then scale up as the ecosystem grows and becomes increasingly open.

As digital platforms and business ecosystems become more widespread, they will increasingly compete based on their governance. Companies that build their own platform and ecosystem can use the frameworks presented in this article to systematically think through the building blocks and options of ecosystem governance and find the right governance model for their ecosystem. Companies that consider joining an ecosystem as complementor or supplier can use the frameworks to analyze an ecosystem’s governance model and assess to which extent it is consistent, fair, effective and flexible and meets the company’s specific requirements.