On November 25th 2020, the European Commission issued its Data Governance Act, the first concrete proposal of how the Commission envisions to implement its vision of the European Data Strategy, shared earlier in 2020. Taking the form of a regulation, this new release is a testimony of Europe’s acknowledgment of the pressing importance of developing and implementing a Data Strategy at the European level, with the aim of boosting its global AI competitiveness in the face of US and China.

The ability to build a strong Data Economy has indeed emerged as a major table stake in recent years. In its first Digital Economy Report, issued in September 2019, The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) found that the United States and China account for half of global spending on the Internet of Things (IoT), more than 75% of the cloud computing market, and as much as 90% of the 70 largest digital platform companies’ market capitalization. According to the report, the “businesses that build digital platforms have a major advantage in the data-driven economy.”

In 2018, a European Commission survey of 129 companies found that 60% did not share data with other companies and 58% did not reuse data obtained from other companies. Little surprise then, that European digital platforms make up less than 10% of the market capitalization of the biggest digital platform companies.

The volume of data is growing fast, especially from IoT (Ericsson projects that the number of IoT-connected devices will more than double from 11 billion in 2019 to 25 billion by 2025), and more companies are engaging in commercial activities that are rooted in data and data sharing. Data is the fuel for advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), that are reshaping national and regional competitiveness. Public policy that puts Europe on a single regulatory footing for the data economy holds many advantages over a fragmented country-by-country approach — not least for European companies seeking to compete with leaders from the US and China.

Where do we stand today?

The subject matter of the newly released Data Governance Act revolves around three key points to create trustworthy data sharing systems:

- Re-use of public data — outlining conditions for the re-use within the EU of certain categories of protected public sector data;

- Trustworthy providers — proposing a notification and supervisory framework for data sharing services providers;

- Data altruism — laying a framework for voluntary registration of entities, which collect and process data made available for altruistic purposes.

It also announces the creation of a European Data Innovation Board, an expert group aimed at steering data governance and facilitating the emergence of best practices across Member States’ Authorities.

With its Data Governance Act, the European Commission targets a value pool of data access and reuse estimated at 1% to 2.5% of GDP and aims at increasing the annual economic value of data sharing by €7–11Bn by 2028.

The Data Governance Act is a first step towards bringing the European Commission’s initial strategy on data and data sharing to life. Released in early 2020, the goals of the European Data Strategy are to make “the EU a leader in a data-driven society” and to create “a single market for data [to] allow it to flow freely within the EU and across sectors for the benefit of businesses, researchers and public administrations.”

The European Data Strategy stated six high-level tenets, aimed at addressing potential data sharing gridlock — with the first three partially addressed by the newly release Data Governance Act:

- Facilitate the set-up of a procurement marketplace for data processing services

- Allow free access and reuse of high value publicly-held datasets across the EU

- Adopt legislative measures on data governance, access and reuse

- Invest in sharing infrastructure, tools, architectures and governance mechanisms

- Foster the roll out of common European data spaces in crucial sectors

- Empower data control and invest in capacity building for SMEs and digital skills

Even if it constitutes a necessary first impulse, the Data Governance Act is largely focused on providing an overarching legislative outline to enable future initiatives, rather than offering a compelling rationale and incentives to encourage them. This is not sufficient to fully unlock the potential of data sharing at the European level. Here’s how the EC can create the conditions that facilitate private-sector data sharing and encourage companies to behave in productive ways as the data economy take shape and avoid the pitfall of complicated legislative measures and regulatory frameworks.

A Smart Simplicity Approach

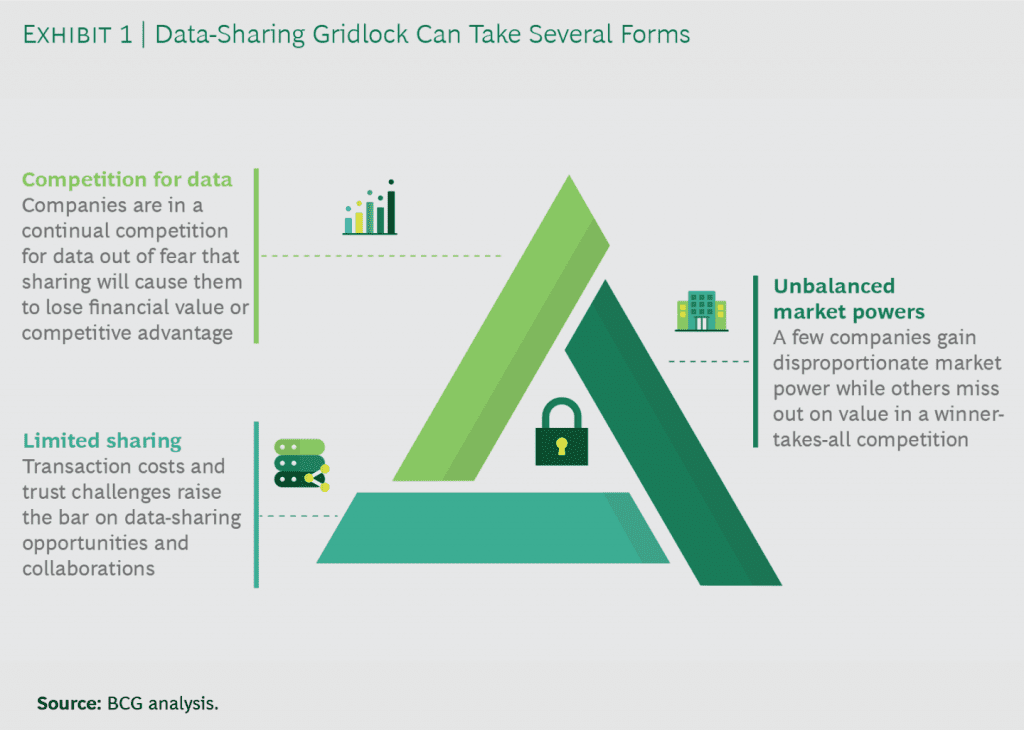

As we observed recently in a different context, data sharing is primarily an exercise in collaboration, and it is easy for barriers to arise that limit sharing and lead to data gridlock [link to governance article]. (See the sidebar, “Data Sharing Ecosystems and Barriers.”) This gridlock can take several forms. (See Exhibit 1.)

- Competition for data: Companies continuously compete for data and data access. Since data is considered crucial to competitive advantage, it is not shared among companies because of fear of losing financial value or competition advantage.

- Unbalanced market powers: Winners (usually digital giants and ecosystem orchestrators) gain disproportionate market power in a winner-takes all competition. Others miss out on value.

- Limited sharing: Transaction costs and trust challenges raise the bar for data sharing opportunities and collaborations.

Simple and effective rules of governance can help prevent this gridlock from occurring. As the EC moves forward with its data strategy, it will benefit from following six rules that we call collectively Smart Simplicity. These rules promote cooperation by helping companies make sense of organizational complexity and empowering participants to improve data sharing performance and compelling them to cooperate.

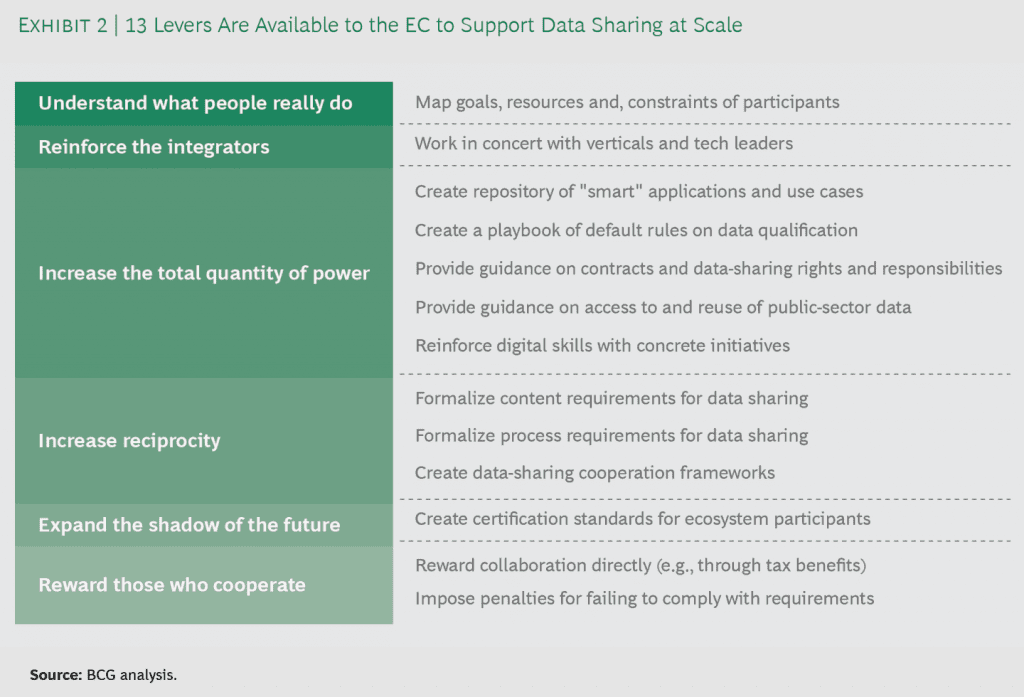

Within this framework, we have identified 13 potential levers to facilitate sharing and avoid gridlock. Many have been tried in one form or another by governments in Europe and elsewhere. These levers do not constitute a policy recommendation; rather, they are intended as illustrations of the Smart Simplicity approach to the data sharing gridlock from which the European Commission could draw inspiration. (See Exhibit 2.)

Rule 1. Understand what people really do. This rule helps identify the criteria for a situation in which everyone wins, thus aligning all stakeholders’ objectives. The goal for Europe is to create the right conditions for the data sharing economy to grow to scale under European guidelines.

The EC can map the goals, resources and constraints of each type of participant in a data sharing ecosystem in order to understand how to create the conditions to unlock a data-sharing virtuous circle. (This also means coming to grips with the constraints on data sharing to date.) It can then set the rules fostering participants’ positive behavior towards data sharing.

This does not mean trying to set up large scale enabling technologies, since the Commission has much less agility and expertise than others (such as leading tech companies) to invest in rapidly changing technology at scale. But there are specific governance mechanisms linked to data and use cases that can be best administered at an ecosystem level, versus a national or multinational. For example, while a government can set foundational requirements on personal privacy, B2B ecosystems can go one step further to protect non-personal, but still sensitive competitive information. In China, the government sets the ‘rules of the playground’ for data sharing and then allows digital leaders and industry incumbents to play the data sharing game to generate value.

Rule 2. Reinforce the integrators. Orchestrators and enablers often play the role of integrators — participants whose influence makes a difference in the work of others. Integrators bring others together and drive processes. This rule aims to create trust in third-party integrators to harness the potential of sharing, while serving each participant’s interests.

The EC has an opportunity to build the foundations of trust necessary for data-sharing ecosystems to take hold through its proposed efforts by creating trusted intermediaries through the Data Governance Act. The newly proposed Act can also support the legitimacy of tech enablers in the eyes of other participants by overseeing and certifying that these companies are operating under EU rules and upholding EU values.

Going beyond the proposed authorization framework for providers of data sharing services, this rule has at least two additional avenues for aligning companies on the benefits of integrators. One avenue is simply to use its ability to bring industry stakeholders together. Another is to continue or improve its funding programs (such as Horizon 2020) for use cases supported by data sharing.

Both will help ensure buy-in from contributors by setting the right conditions for contributors to select their integrators (rather than regulators selecting integrators directly). In the US, the American Farm Bureau Federation, together with commodity groups, farm organizations, and agriculture technology providers, helped establish the Privacy and Security Principles for Farm Data, which addresses controversial issues related to the ownership of agricultural data. More than 30 organizations have signed onto the core principles, pledging to incorporate them into their contracts with farmers.

Rule 3. Increase the total quantity of power. Governance systems should make data sharing attractive by empowering contributors and enablers with tools while protecting their interests. The first opportunity is to highlight “smart” applications and use cases that showcase the kinds of value that data sharing can unlock. By making the benefits of sharing obvious and concrete to everyone, a registry of “smart” applications and use cases has the potential to level the playing field while empowering contributors with knowledge to efficiently identify which data to share, and for what objective. For example, the German government’s mFUND research initiative centralizes key use cases to develop data-based business models for smart mobility. This initiative aims at incentivizing digital innovations in the transport sector, such as new navigation services, smart journey planners and highly accurate weather apps. Data access and sharing are promoted according to open data principles and supported technically by the creation of central, open data access points for mobility-related data. More than 100 projects have already been already funded with more than 300 individual project partners, including enterprises, research institutions and universities.

Second, the EC can create a playbook that provides general guidelines and default rules on how to qualify and assess the value of data.

Third, the EC can provide clear legal explanation and tools that help companies navigate the complexity of data sharing. Reassuring companies with the effective tools (such as contract templates) can help build confidence in and reduce resistance to sharing. Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry has issued “Contract Guidance on Utilization of AI and Data” as a reference for companies that summarizes issues and factors to be considered when drafting a contract involving the use of AI or data. The guidance provides in-depth explanations and illustrates actual examples of data utilization contracts and explains basic concepts concerning rights and responsibilities associated with development and utilization of AI-based software and the use of data.

Fourth, the EC can supplement its newly created mechanism for re-use of public sector data to further expand the quantity of free data made available to companies by offering a turnkey experience with open public data to showcase value and encourage later sharing of private sector data. Denmark has brought together efforts to promote open data across the various government siloes in order to encourage access and reuse. It provides a common architecture for sharing and reuse of public-sector data and offers clear framework for conditions of use. The government also draws attention to the value of using data through hackathons and the establishment of data exchanges spaces wherein public and private entities can share data.

Finally, the EC can clarify its tenet on reinforcing digital skills with more concrete initiatives. In the UK, the Digital Skills Partnership brings together public, private, and charity sector organizations to boost skills for a world-leading, inclusive digital economy. The Data Skills Taskforce works with the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, public bodies such as The Tech Partnership, and private partners to enhance data analytic skills in the workforce.

Rule 4. Increase reciprocity. The success of each participant in the ecosystem depends on the success of others. Good governance makes obvious the benefits of mutual sharing and helps prevent the possibility of benefiting without also contributing.

The EC has an opportunity to increase protection of small players, which is important since rivalries and competition can make companies reluctant to reciprocally share with trust. Such protection can take the form of data-sharing cooperation agreement frameworks. The Netherlands’ Dare-2-Share Co-operation Agreement aims at helping entrepreneurs “establish agreements in an honest and reliable way in the ‘collaboration in innovation’ phase — where data are shared between large and small companies” with particular attention on the relationships between small players and larger entities. It defines the legal standards and references to national and international laws, and regulations that parties need to consider in their agreements.

Going a step further than its newly proposed authorization framework and standard consent form for data altruism, the EC can also formalize standard requirements for participating in data sharing in terms of content (data quality threshold or standard formats) and process (security, transparency and privacy). This facilitates interoperability, thus enabling reciprocal sharing by reassuring parties on similar quality thresholds and standards met, increasing willingness to share. The government of Singapore established a “Trusted Data Sharing Framework” to boost data sharing, drive the new product and service development, and establish confidence that data is safeguarded. The framework consolidates a common data-sharing syntax to help businesses establish baseline practices on sharing strategies and legal and regulatory considerations. It contains a guide to data valuation, technical models and processes to ensure transparency during and after data exchange.

Rule 5. Expand the shadow of the future. Make clear potential consequences resulting from participants’ behavior and decisions by illustrating how success is achieved by contributing to the success of others, and is a cornerstone of collaboration. To do so, The EC can create certification standards rewarding trustworthy ecosystems and companies thereby establishing the possibility of losing accreditation if requirements are not respected. Under Japan’s Certification System for data sharing platforms, data sharing companies are certified to foster trust among sharers and certified companies can request data from others thus promoting reciprocity.

Rule 6. Reward those who cooperate. Direct incentives for sharing (and disincentives for hoarding) through rewards or penalties are powerful motivators. The EC can create direct rewards, or set penalties, with tax incentives and administrative advantage for those that cooperate or tax penalties for companies that fail to comply with standard requirements. Through Japan’s Certification System for data-sharing platforms, the government provides support through tax incentives and administrative guidance. It can also revoke accreditation in some cases.

The European Data Governance Act addresses a clear opportunity: increasing data sharing to achieve valuable use cases and establish European digital competitiveness. If the newly released Act is a first step in the right direction towards the implementation of the European Data Strategy, it still leaves room for complementary initiatives “to walk the talk”. A Smart Simplicity approach can help the EC clarify and complete the proposed tenets by working with individual industries and tech leaders to address the potential for data sharing gridlock and focusing its efforts on the most high-impact initiatives. Similar efforts have been successfully deployed in European and other countries and the EC can draw inspiration from their success to unlock data sharing at scale. The challenge increases in urgency as alleviating data gridlock at a European level is essential in the race for AI competitiveness and other advanced technologies.