The upheaval of 2020 has shone a light on the value of resilience in business. Resilience can be defined as the capacity of a firm to outperform during a crisis by absorbing stress, recovering critical functionality, and thriving in altered circumstances. Evidence shows that resilience is a key driver of long-run performance: over the past 25 years, firms that outperformed their industry during crises were twice as likely to outperform in the long run. In fact, crisis performance had more than three times the impact on long term TSR as performance during stable periods.

Leaders are now looking to re-build their firms as all-weather companies that can thrive in any economic environment. This requires investing in capabilities and structures that increase resilience. However, this creates a tricky tradeoff: such investments can reduce short-term efficiency, while the benefits of resilience are uncertain and only accrue over the long term. How should leaders think about making this tradeoff?

A difficult tradeoff

The traditional managerial approach to making tradeoffs across time is to project benefits and weigh them against costs using discounted cash flow analysis. For example, consider a firm evaluating the merits of diversifying its supplier base to build resilience against a potential disruption to operations at one of its current suppliers. Such an approach would be to project the expected benefits from having redundant suppliers into the future, apply a discount rate to calculate the net present value of those benefits, and weigh that against the costs (such as increased complexity and reduced economies of scale) involved with such a decision. However, such an approach has some important limitations and flaws for assessing tradeoffs between efficiency and resilience.

For one, the benefits of resilience may only surface during a crisis; but the frequency, impact, and nature of crises are impossible to predict. Firms today operate in complex, interconnected environments where even small changes in unrelated areas can have ripple effects and manifest into full-fledged shocks that affect the firm. This poses a challenge in quantifying the value of resilience. For example, to forecast the benefits from building new supplier relationships, we would have to know how often shocks will affect existing suppliers and how severe they will be — an impossible task given the growing and changing types of risks in an increasingly interconnected world.

Moreover, an approach that focuses only on the expected value of future benefits is limited if it does not account for the possibility of corporate failure. A financial projection might find that on average the benefits of having redundant suppliers are not worth the long-run costs associated with maintaining multiple sub-scale supplier relationships. However, if the company could go bankrupt under some scenarios without the redundancy in its supplier base, the argument about long-run loss of efficiency becomes moot. In this stylized example, not diversifying the supplier base can be analogized to the “Gambler’s Ruin” phenomenon — the strategy may have a positive long-run expected value but a near-certain probability of failure. For example, if there is a 90% chance of doubling your investment each year and a 10% chance of going bust, the expected gain is 80% per year — but over a long enough timeframe it becomes nearly 100% certain that you will eventually lose everything.

Finally, such a forecasting-based approach to making tradeoffs is not well suited for the path-dependent nature of crisis responses. The value of resilience is not limited to the level of sustained operations; resilient firms can also respond to crises opportunistically in ways that also reshape their business landscape. For example, a company that outperforms during a crisis may take advantage of its position to acquire a struggling peer or enter a new market, with long-term benefits. Such opportunities are valuable, but they cannot be easily quantified.

These challenges complicate quantifying the tradeoff between efficiency and resilience. This does not mean that models that aim to project the impact of crises or value the benefits of resilience are useless — they can still help leaders understand how different scenarios could impact their firm — but given the uncertainties involved, they are less suitable for calibrating investments in resilience. Instead, today’s leaders need a new playbook to make well-calibrated tradeoffs between resilience and efficiency.

Principles to calibrate the tradeoff

If the traditional approach for calibrating tradeoffs between resilience and efficiency is inadequate, how can business leaders make informed decisions? The study of other disciplines, such as complex systems science and biology, reveals some alternative principles and strategies for making tradeoffs that can be applied to the challenge.

Satisfice:

Under situations of high complexity and uncertainty, finding optimal solutions to problems is sometimes not feasible. A principle which can be used in these situations is satisficing: following a simple heuristic that is “good enough”. The idea that satisficing can be advantageous in business might surprise some, as it stands in stark contrast to the reigning culture of optimization. However, research has shown that satisficing is not merely expedient in its simplicity, but it also has positive advantages.

Satisficing solutions are generally faster and easier to implement because they are based on simple heuristics. For example, one satisficing strategy to make tradeoffs between efficiency and resilience is to ‘build enough resilience to survive plausible downside scenarios.’ While this does not necessarily yield an optimal outcome, it provides firms with a simple rule of thumb to calibrate tradeoffs that can be executed quickly; knowing that the firm cannot survive plausible test scenarios is a clear indicator that the current tradeoff is not well-calibrated and more resilience is required. On the other hand, an initiative to find an optimal tradeoff point would require extensive data collection and computationally intensive analyses of all future possibilities — a time-consuming exercise that is likely to be outdated before it is complete.

To execute such a satisficing approach effectively, leaders need to test their companies against a range of plausible scenarios, which may be phenomenon-based (“would our business survive if a global pandemic struck?”) or outcome-based (“would our business survive if revenues declined by 30% for any reason?”). A variation of this approach is to use satisficing to define a feasible option set and optimize subject to that constraint. Such an approach is currently used by major banks worldwide (enforced by regulators after the 2008 financial crisis). Banks are obligated to meet certain capital requirements at all times, and under a range of hypothetical stress scenarios, but they are free to optimize tradeoffs subject to those constraints. The relative resilience of banks amid Covid-19 compared to past crises is a testament to the value of such an approach.

Another benefit of satisficing strategies is that they are robust across a greater range of situations than tightly optimized solutions. For example, during COVID-19, governments faced the tradeoff between mitigating disease spread and allowing economic activity. Research showed that a strategy of short, precisely timed lockdowns was the optimal solution to this tradeoff with perfect information, but also that this solution was extremely fragile — it became highly ineffective with even small errors in data, analysis, execution, or timing. In contrast, satisficing solutions (such as sustained but less severe social distancing) were much more robust in controlling the disease under a wide range of uncertainties.

Learn:

Another principle that can be used to make tradeoffs across time is to learn from experience.

One learning strategy is to assess the firm’s resilience to past crises. Crises provide leaders with valuable intelligence by shining light on poorly calibrated tradeoffs. Leaders should use every crisis to critically evaluate their company’s tradeoffs and adjust their approach if needed: Was the firm sufficiently prepared? Which resilience mechanisms worked better or worse than expected? To this end, organizations can institute reflection sessions as part of their planning processes to conduct post-mortems on crisis performance and diagnose what they should do differently. For example, certain East Asian regions such as Taiwan studied the SARS epidemic and used the learnings to recalibrate their pandemic response plans. As a result, they were better prepared when COVID-19 struck.

Another learning strategy is to understand the distribution of historical shocks. Of course, historical crises will not cover all potential shocks, as evidenced by recent crises that were without precedent. But for threats that follow power-law distributions, such as stock market crashes, the likelihood of shocks of unprecedented magnitude can be roughly calibrated, even if specific events cannot be predicted. For example, while individual earthquakes are unforecastable, their distribution of intensity and frequency follows a power law. So regulators can assess the likelihood of an earthquake of a certain magnitude when designing building codes. Similarly, business leaders can calibrate the required level of investment in resilience by using power-law distributions to identify the likelihood of shocks one or two orders of magnitude greater than those experienced in the recent past. Of course such an analysis should also not be taken as an absolute guarantee — circumstances and distributions can change.

Adapt:

Because of constant change in today’s business environment, the desired tradeoff between efficiency and resilience may change over time. A guiding principle embraced by resilient entities in such environments is adaptivity: the ability to rapidly recalibrate tradeoffs as needed. Firms should similarly stay alert to changes in their environment and rapidly recalibrate tradeoffs as needed. To this end, firms can build optionality into the business, develop reversible response systems, and enhance business agility to become more adaptive.

Maintaining optionality provides firms with a low-cost way to act on new information and quickly recalibrate between resilience and efficiency. For example, cash buffers build resilience in firms because having liquidity is crucial during a crisis. But instead of raising capital preemptively (permanently building a cash buffer) or after a crisis hits (when raising cash may be too slow or no longer possible), firms can choose to keep a revolving line of credit open. This gives firms the option to quickly raise cash (albeit at a cost) when they sense distress, rapidly trading off efficiency in favor of resilience.

Developing reversible response systems allows firms to make temporary changes to their tradeoff in response to short term shocks, which can then be reversed. This can help firms avoid becoming locked into arrangements that may be costly or constraining. For example, for a firm looking to increase short term resilience during a crisis by reducing personnel costs, furloughing employees, or temporarily reducing pay is preferable to layoffs. The former is a temporary tradeoff that can be quickly reversed, while the latter risks leaving the firm under-resourced to capitalize on a rebound, hurting long term efficiency.

Finally, enhancing business agility can help firms stay nimble and rapidly recalibrate tradeoffs between efficiency and resilience in response to changes in the external environment. Firms can build business agility by staying alert to environmental changes, experimenting quickly and economically with products, processes, and business models, and rapidly mobilizing resources to scale winning strategies. In fact, while the measures discussed so far have involved explicit tradeoffs between resilience and efficiency, enhancing business agility has the potential to break that tradeoff. Accelerating the clock-speed of an organization increases efficiency by helping firms implement desired actions faster, and also increases resilience by reducing the reaction time to adapt to shocks.

Applying the principles in a competitive environment

The strategies above examined how the three principles (Satisfice, Learn, and Adapt) can help firms calibrate tradeoffs between efficiency and resilience in an isolated setting. However, leaders can also think about these principles from a competitive perspective, where outcomes depend not just on a firm’s actions but their competitors’ actions as well. Doing so yields additional strategies to help calibrate tradeoffs.

A competitive perspective provides new heuristics that can be used to calibrate the tradeoff. For instance, we have seen that resilience is a strong driver of long-term competitive outperformance. Thus, a competitive satisficing strategy, such as “being more resilient than competitors” can be a useful heuristic to calibrate the tradeoff between resilience and efficiency. Such an approach can ensure that firms are advantaged in case of a shock, in turn making it likely that they will outperform their peers in the long-run.

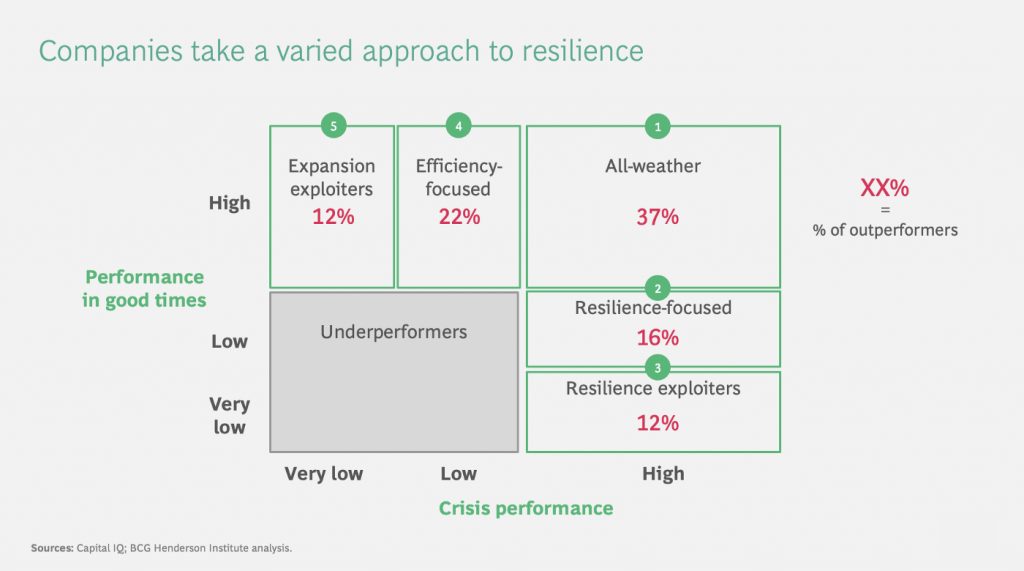

However, calibrating resilience relative to competitors is not a trivial task. Our research has shown that companies have historically taken different approaches to the efficiency vs. resilience tradeoff, leading to a wide spread of outcomes (See exhibit 1). This gives firms the chance to learn from the approach taken by their peers during past crises: What levers do competitors use to make tradeoffs? What do peers who perform well in crises do differently from others? Which strategies have been most effective in a given industry?

Finally, competitors may pursue influencer strategies such as baiting, interfering, spoiling, and cooperating to influence tradeoffs made by their peers:

- Baiting strategies: Certain competitors may decrease their resilience levels to bait competition into similarly trading off resilience in favor of efficiency (e.g., by announcing plans for a large share repurchase program, forcing other companies to follow suit to attract investors).

- Interference strategies: On the other hand, competitors may reduce their efficiency to build resilience at the expense of their competitors (e.g., by paying upfront for preferential access to scarce resources from common suppliers during potential shortages).

- Spoiler strategies: Some competitors may choose to voluntarily sacrifice both their resilience and efficiency levels if it makes their competition comparatively worse off on both dimensions (e.g., by cutting prices during times of crises, reducing short-term efficiency and buffer to survive the crisis but forcing peers to do the same to remain competitive).

- Cooperative strategies: Competitors may come together to share resources, capabilities, and expertise to increase their collective efficiency and/or resilience (e.g., by investing in a joint venture, or by coordinating on crisis response).

Firms must equip themselves to rapidly adapt their resilience-efficiency position in response to competitor moves and invest in counterstrategies. Leaders need to stay alert to such moves and devise their own influencer strategies to stay competitive in the long run.

Making tradeoffs between resilience and efficiency is challenging, as traditional optimization approaches are not well-suited for the task. But the knotty challenge cannot be avoided — under-investing in efficiency can cause a crippling lack of competitiveness, while under-investing in resilience can cause corporate failure or long term competitive disadvantage. By adopting alternative principles and strategies, leaders can make more effective tradeoffs between resilience and efficiency and position their organizations to win in the long term.