A large, multinational organization is about to undertake an ambitious transformation effort. To do this, they hire a seasoned Chief Transformation Office who promptly sets up a Project Management Office (PMO) and begins to roll out detailed plans, carefully defined milestones, and a battery of Gantt charts.

While this is a common scene across corporate transformation programs, our research has shown that only ~25% of such efforts succeed in both the short and long terms. Given this unimpressive track record, why do we keep relying on the same traditional change management tactics time after time?

Changing Change Management

Part of the problem is that the presumed supremacy of classical change management techniques blinds leaders to the variety of organizational contexts in which change occurs. Leaders therefore tend to rely on those standard approaches, rather than adapting their change strategy to their specific situation. Effective change management instead requires leaders to shift away from one-size-fits-all approaches and develop an expanded set of context-specific strategies.

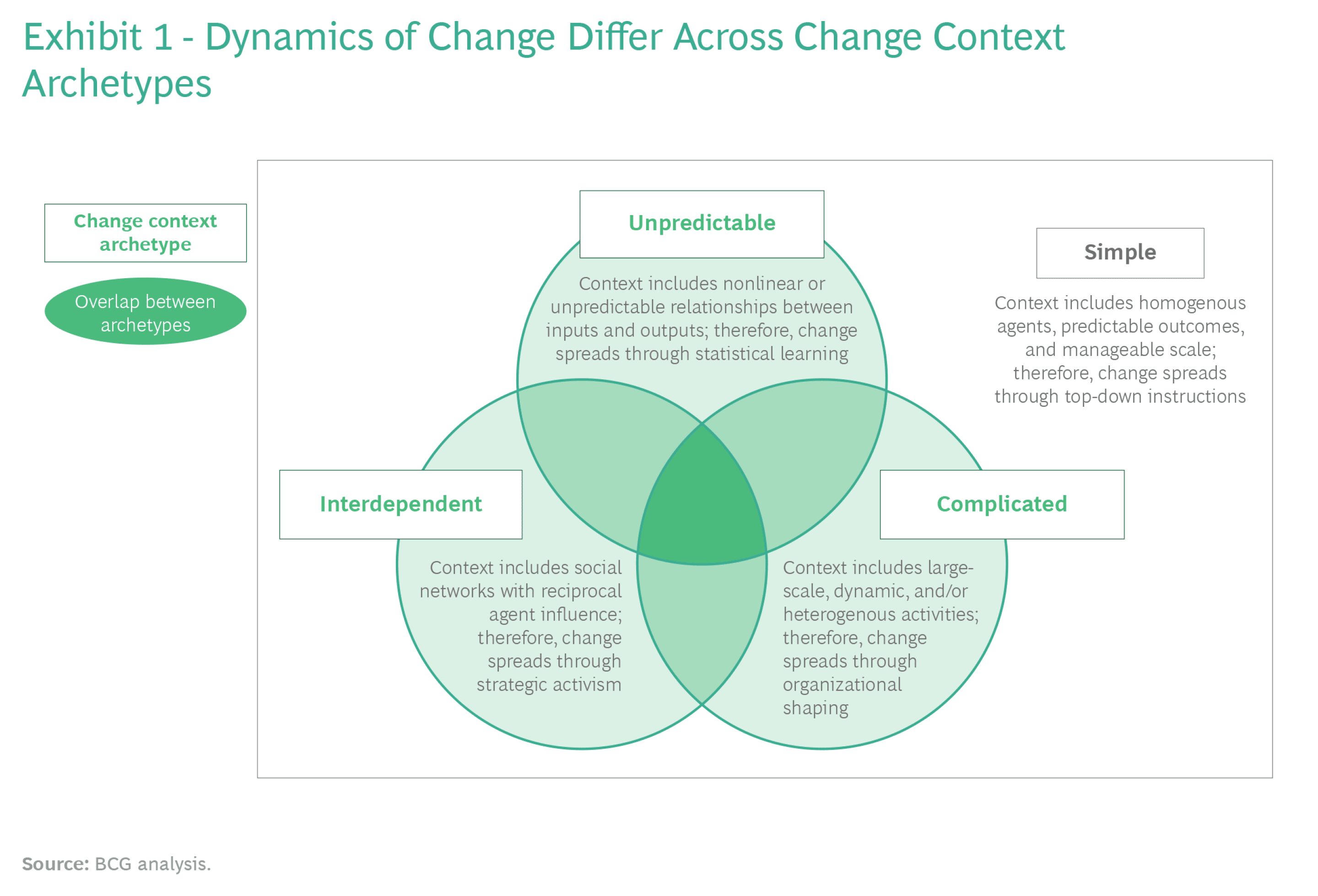

An effective change strategy begins with an understanding of the specific mechanisms of change, as determined by the change context. We define a change context as the pattern of endogenous factors which shape how change spreads. Though change contexts can vary widely across organizations, leaders can benefit from recognizing a few salient archetypes from which more nuanced strategies can be constructed.

This article focuses on four key archetypes for change contexts. Simple change contexts are those in which agents are homogenous, predictable, and manageable. Unpredictable change contexts are those in which the relationships between inputs and outputs are unclear, so that the effects of specific interventions are hard to predict. Interdependent contexts are those characterized by networks of reciprocal interactions, in which social influence from peers has a stronger impact on agents’ behaviors than top-down influence. Finally, complicated contexts are those that are large in scale, comprised of heterogenous agents, and/or dynamic. These archetypes do not exhaust the full variety of possible change contexts. However, they highlight some ways in which change efforts need to depart from traditional change management techniques to be effective in specific contexts.

Each of these archetypes is associated with a characteristic family of interventions able to spread change within a given context. While traditional change management techniques work well in simple change contexts, they are less effective in unpredictable, interdependent, and complicated environments. To illustrate this idea, we have designed a change simulator that generates organizational networks to embody these different change contexts and models how they respond to different interventions.

As traditional sources of competitive advantage decline in persistence, increasing the speed at which leading companies are overtaken by competitors employing different business models, effective change management will become increasingly critical to success — and even survival. Therefore, instead of defaulting to the standard change management methods, leaders should adopt appropriate strategies of change that respond to the specific characteristics of the change context and adapt as the organization evolves.

Our proposed framework — which pairs context archetypes and appropriate interventions under holistic change philosophies — together with the change simulator, can help managers navigate a wider range of options to transform the organizations they lead.

Understanding Change Contexts

Depending on the intended change effort, a change context may encompass the entire organization or only a part, like a single team. In either case, leaders need to understand how that context works — what drives agents’ current behaviors, and what would be needed to change them. Leaders can do this by assessing individual change contexts against one of the four change context archetypes.

- Simple contexts are those in which agents and activities are directly manageable. Such contexts are characterized by relatively homogenous agents, interventions that have predictable outcomes, manageable scale, and agents that are responsive to top-down influence. These are contexts in which traditional change management works well and should be deployed. But leaders will often encounter contexts that depart from this simple archetype.

- Unpredictable contexts are those in which leaders cannot predict the outcomes of interventions. For example, imagine that Company A wants to increase its rate of product innovation. However, it cannot simply mandate that employees submit new or better ideas because leaders will be unable to predict which employees will respond to this request, as well as how the types and styles of employee submissions will differ. This is because employee responses depend primarily on the employees’ interests and capabilities and are, therefore, difficult to anticipate.Because outcomes in this context are unpredictable and their odds are unknown — and thus difficult to manage directly — change can most effectively be shaped by systematizing learning across the organization. To do this, leaders can create statistical learning systems which encourage experimentation, aggregate learnings, and iteratively adapt approaches to bring about the desired change.

- Interdependent contexts are those in which peer influence is stronger than top-down directives. This is true when agents are connected through robust and reciprocal social networks, resulting in stronger horizontal influence than top-down mandates can exert.Suppose Company B is having trouble getting employees to buy into their new ethical AI policies, which encourage people to report any potential harms or risks associated with their projects — such as applying AI software to determine hiring criteria.[1]https://hbr.org/2019/04/the-legal-and-ethical-implications-of-using-ai-in-hiring Rather than following company-wide guidelines, individuals may tend to report concerns only if other people to whom they are socially connected do so as well.This makes sense if people are more personally invested in the perceptions of members of their social groups — especially those with whom they interact frequently — than in the interests of company leadership.In an interdependent context, change spreads primarily through reciprocal agent influence. Leaders can, therefore, spread change through strategic activism — the use of peer influence, interpersonal interventions, and incentives to amplify beneficial behaviors.

- In complicated contexts, activities or agents are large in scale, heterogenous, and/or dynamic. These factors make direct management difficult even when outcomes are predictable and leadership retains a strong influence. Imagine that Company C, a large, multinational organization, is just returning to the office following the COVID-19 pandemic. To avoid outbreaks across its various offices and regions, leaders want to increase employee vaccination rates.However, solving this problem involves navigating the ever-changing nature of the pandemic, understanding numerous regional and local COVID regulations and vaccine availabilities, and addressing diverse — and potentially contradictory — employee opinions related to vaccine compliance. A one-size-fits-all, top-down solution will likely not work. When facing a complicated change context, leaders can seek to transform it into a simpler one by, for instance, implementing mandates that standardize behavior or dividing the organization into smaller units. Furthermore, by using exploratory probes, tests, and pilots, leaders can learn how to reduce the influence of complicating factors.

In reality, of course, change contexts are rarely pure archetypes. Therefore, leaders must understand the extent to which their context is unpredictable, interdependent, or complicated. In fact, a change context may be all of these things at once — as in many large-scale transformations — and the context itself may evolve over time. Understanding this will better enable leaders to identify the most effective interventions for their specific situation.

Choosing Appropriate Interventions

Once a change context has been properly understood in terms of its unpredictability, interdependence, or complicatedness, leaders will be better able to identify the most effective interventions to advance their change efforts.

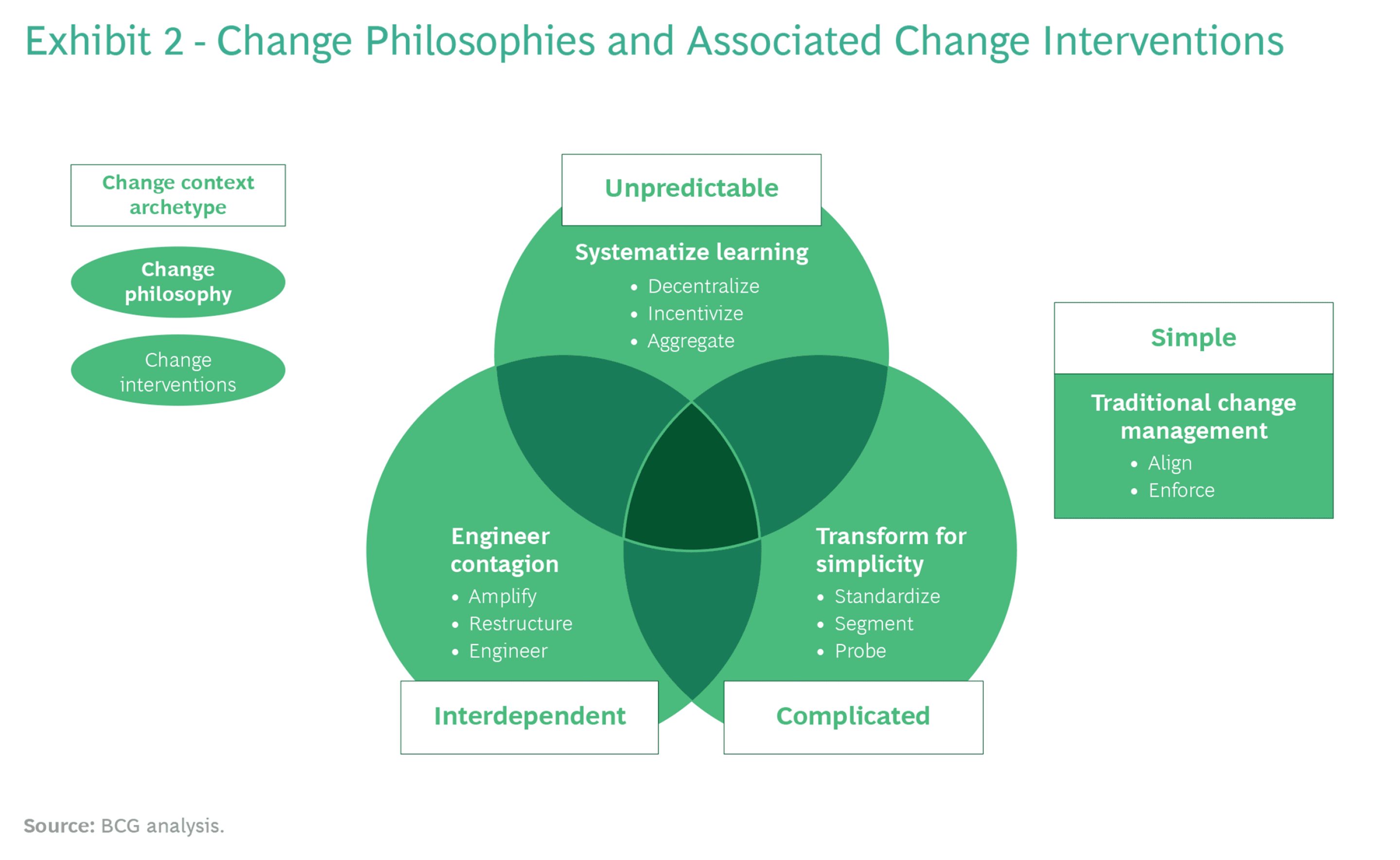

The appropriateness of individual interventions varies across contexts and over time within the same organization. For this reason, rather than picking from a long list of potential interventions, we encourage leaders to think in terms of coherent change philosophies. A change philosophy is a holistic approach to change that helps organizations deploy a set of interventions which are well-suited to each change context.

The following change philosophies correspond to the change context archetypes described in the previous section:

- Traditional change management | Interventions that rely on top-down influence are the most effective ones for simple contexts because change can be easily managed directly through unilateral and uniform leadership mandates. Interventions that support traditional change management are those that align the organization by developing plans and assigning decomposable task sets to agents and enforce these activities through tracking and directly managing implementation. These approaches generally assume that the change problem is both knowable and relatively static.These interventions embody the change philosophy of Traditional Change Management, which enables leaders to directly manage activities across the organization through top-down instructions. This is the philosophy with which most leaders will already be familiar, and it is relevant in many common change scenarios. But the success rate of traditional change management confirms that it isn’t well suited to every change context.

- Systematizing Learning | Interventions that allow for iterative adaptation are the most effective ones for unpredictable contexts where the relationship between inputs and outputs is not deterministic. Interventions that enable statistical learning are those that decentralize learning opportunities by creating a distributed ability to gather data and test solutions (e.g., redistributing funds to support pilot programs); incentivize experimentation by actively encouraging the controlled exploration and testing of new solutions (e.g., creating innovation competitions); and aggregate learnings by creating feedback loops to compile, assess, select and disseminate learnings about effective solutions across the organization (e.g., utilizing analytical software to assess change progress).These interventions embody the change philosophy of Systematizing Learning, which enables leaders to discover patterns in the organization’s behavior and thus refine their change effort over time.[2]https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.460.8342&rep=rep1&type=pdfFor Company A to be successful in increasing product innovation (as discussed in the previous section), they will need to create learning systems across their organization. The leaders of Company A can use such interventions to increase employees’ interest in and ability to create new products.

In fact, this is precisely the approach taken by Recruit Holdings. Recruit holds two annual events for employees to present new business ideas.[3]https://recruit-holdings.com/sustainability/people-workplace/management/ Teams are given funding to explore their ideas, and the winning teams have their ideas implemented and are recognized throughout the company. Employees are strongly incentivized to participate in the events and have quickly learned how to effectively pitch innovative proposals. As a result, Recruit has generated almost $800M in revenue thanks to ideas that have come from employees’ initiatives.

- Engineering Contagion | Interventions that intentionally shape peer influence are the most effective ones for interdependent contexts because reciprocal agent influence is the primary driver of change. For example, in the case of fisheries management, norms around harvesting behavior can be reinforced through social mechanisms — such as ostracism — in order to promote cooperative behavior.[4]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310899571_Maintaining_cooperation_in_social-ecological_systems_Effective_bottom-up_management_often_requires_sub-optimal_resource_use To spread change in an interdependent context, managers can amplify beneficial behaviors by publicly highlighting agents that demonstrate desired traits (e.g., appointing champions); restructure connections by reshaping the organization’s social network to link distinct individuals and groups (e.g., developing integrated product teams); and engineer interactions by bringing agents together around mutually beneficial goals or ideas (e.g., creating innovation clubs).These interventions embody a change philosophy we call Engineering Contagion, which enables leaders to leverage the organization’s own networks of reciprocal influence. In this context, however, leaders should avoid the temptation of overly simplifying or engineering information to accelerate change. This can lead to social polarization, which, in turn, can make change more difficult.[5]https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsif.2019.0196Let’s take another look at Company B, which is attempting to encourage employees to comply with their ethical AI policies and practices. To do so, the company’s leaders need to engineer contagion and use “strategic activism” to encourage employees to report concerns. Microsoft offers a clear example of this philosophy in action. To spread their Responsible AI strategy, Microsoft’s leadership has appointed and trained Responsible AI Champions to sit on teams across the company.[6]https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2021/01/19/microsoft-responsible-ai-program/ These Champions are responsible for raising awareness of the Responsible AI principles, and they have built an organizational culture centered around AI ethics.

- Transforming for Simplicity | Interventions that segment and simplify the organization are the most effective ones for complicated contexts. These interventions enable leaders to eliminate some of the factors driving complicatedness, such as scale or heterogeneity. More generally, complicated environments should be addressed through the notion of bounded rationality, which encourages people to “satisfice” rather than “optimize,” thereby creating solutions that are “good enough” given the information they have even if they are not perfectly effective.[7]https://msuweb.montclair.edu/~lebelp/ConliskBdRationalJEL1996.pdf In contrast to optimizing, satisficing allows for progress while still leaving room for further improvement, and it also reduces the complexity of interventions.[8]http://innovbfa.viabloga.com/files/Herbert_Simon___theories_of_bounded_rationality___1972.pdf/ In order to simplify complicated change contexts, leaders can standardize behaviors to constrain the effects of agent heterogeneity (e.g., standardizing RACI charts); segment the organization by creating smaller, simpler organizational units that are easier to manage (e.g., sub-dividing large teams); or probe the system to better understand how the organization responds to different stimuli, even if the reasons and limits of this are not understood in detail (e.g., piloting change activities with small groups).These interventions embody a change philosophy we call Transforming for Simplicity, which enables leaders to reduce the impact of heterogeneity and scale and allow for adaptation to changing conditions.Recall Company C’s attempts to increase vaccination rates among employees. The company exists across multiple countries and has a large employee base, so scale will pose a challenge to implementation. Furthermore, there will be regional and individual differences in vaccine sentiment. No single, one-size-fits-all approach will work. Walmart found itself in such a situation in 2021, as it sought to ensure employee and customer safety in its facilities. Early in the pandemic, Walmart instituted uniform social distancing and mask mandates in its facilities for all employees, eliminating the heterogeneity caused by diverse personal beliefs. Later, as vaccines were released, the company adapted their policies to the changing conditions, mandating mask wearing and social distancing only for unvaccinated employees. However, as the Delta Variant spread throughout the US, Walmart tried a new tactic and segmented the organization into groups based on local conditions, requiring all employees in areas of high transmission — but not in other regions — to wear masks in their facilities regardless of vaccination status.[9]https://corporate.walmart.com/newsroom/2021/05/14/new-guidance-to-walmart-u-s-field-associates-regarding-masks-and-vaccinations; https://corporate.walmart.com/important-store-info

These change philosophies should be deployed within the context for which they are best suited. When leaders encounter change contexts that combine traits of unpredictability, interdependence, or complicatedness, they should deploy the appropriate combination of interventions.

We built a change simulator to illustrate how the effectiveness of change interventions varies according to the change context. To do this, the model creates organizational networks with differing degrees of interdependence, unpredictability, and complicatedness and tests the effectiveness and dynamics of different interventions.

The Change Simulator

The change simulator is an agent-based model designed to explore the spread of change across an organization. The simulator randomly generates organizations that correspond to the four change context archetypes: simplicity, unpredictability, interdependence, and complicatedness. Each organization is comprised of a network of heterogenous agents whose individual profiles determine how likely they are to change their behavior both in general and in response to specific pressures. For example, agents in an organization characterized by interdependence tend to conform their behavior to that of their peers rather than leadership behavior.

The simulator models change by defining a target behavior for each agent and applying interventions that exert behavioral pressure through leaders, peers, or information provided. Because the organization is a complex, partially connected network of heterogenous agents which possesses inertia, change is not instantaneous. Instead, each time an intervention is applied, it results in a modified organizational profile, with agents adjusting to the applied intervention to varying degrees. The modified network then responds to subsequent interventions differently than the original network would have. Through this process, the simulator can show the dynamics of change spreading over time, including the limits and reversals resulting from specific interventions.

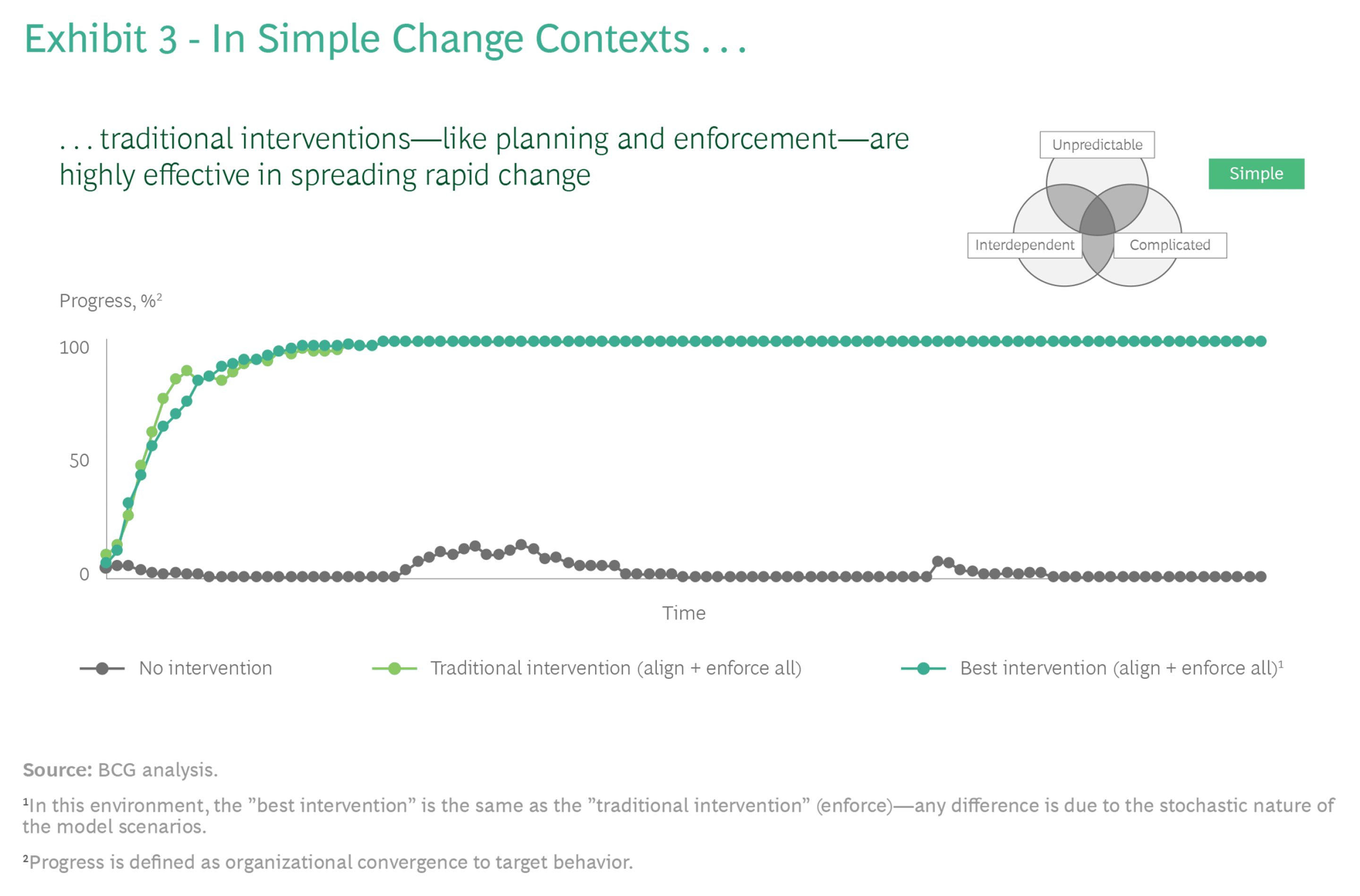

Simplicity. First, we illustrate the simple archetype, with relatively homogenous and disconnected agents and predictable dynamics. In this context, leaders can declare a new target behavior and generally expect most employees to eventually comply without further intervention. Therefore, the most effective interventions are to align leadership instructions with the target behaviors and to enforce this:

We have used this combination of interventions (align and enforce) across the remaining change context simulations as a proxy for traditional change management methods in order to illustrate how alternative interventions can be more effective in unpredictable, interdependent, and complicated contexts.

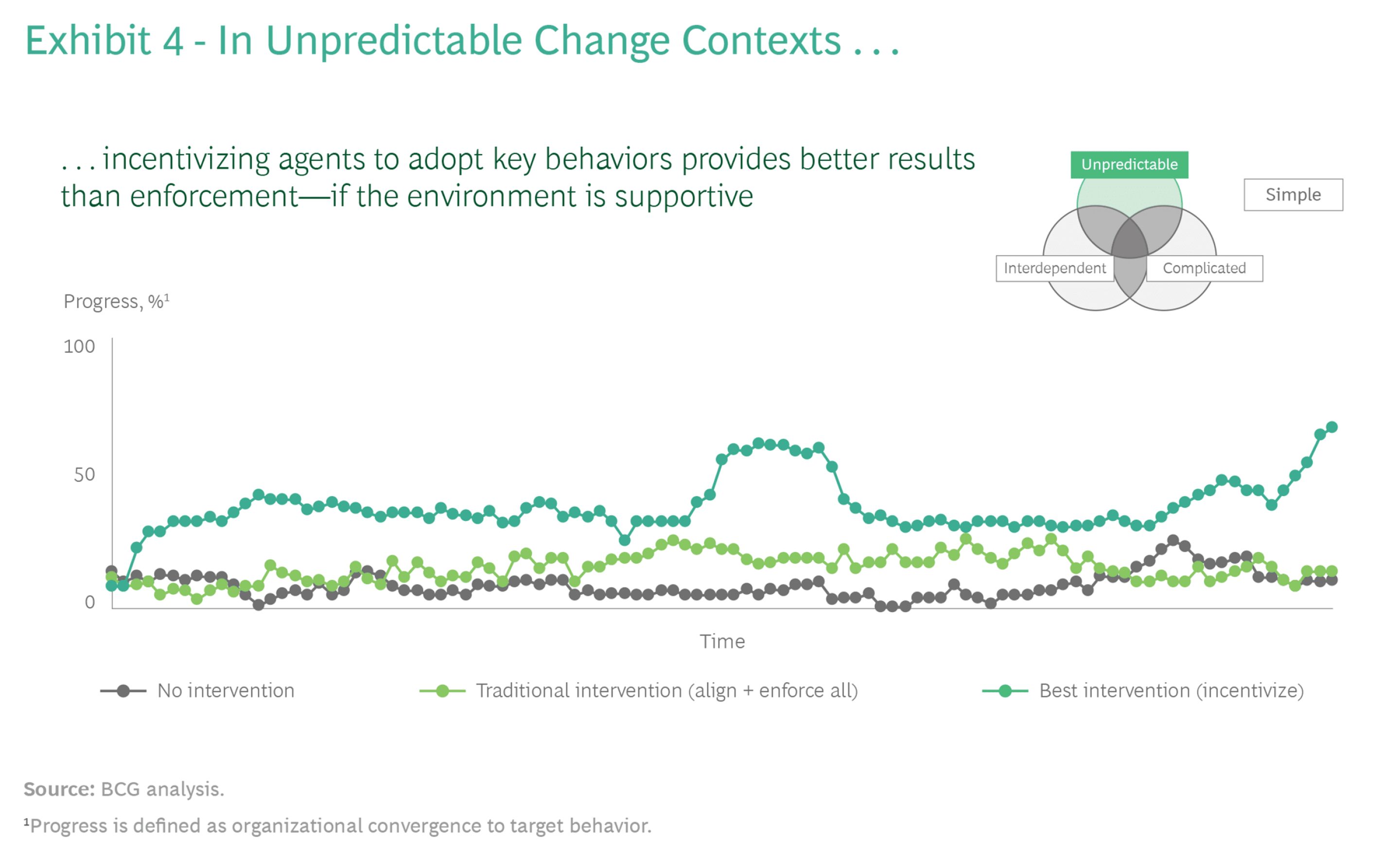

Unpredictability. In the next simulation, we tested the performance of different interventions in unpredictable change contexts. In this case, agents who change their behavior in response to leadership instructions will adopt a stochastic response, and so top-down change management efforts will be largely ineffective. Consequently, leaders must encourage systematized learning across the organization to uncover response patterns.

Leaders can incentivize agents to actively explore the environment for traits that match the target behavior; these incentives will then increase the pressure on agents to adopt the new behavioral traits, supporting bottom-up learning. However, due to the strong influence of the environment in unpredictable contexts, incentives will only be effective in producing desired behaviors while the environment reinforces those behaviors. Leaders must do what they can to provide productive learning conditions and reduce negative influence. Agents’ responses — or lack thereof — to incentives will teach leaders more about the characteristic desires or interests of their organizations, which can inform future strategies.

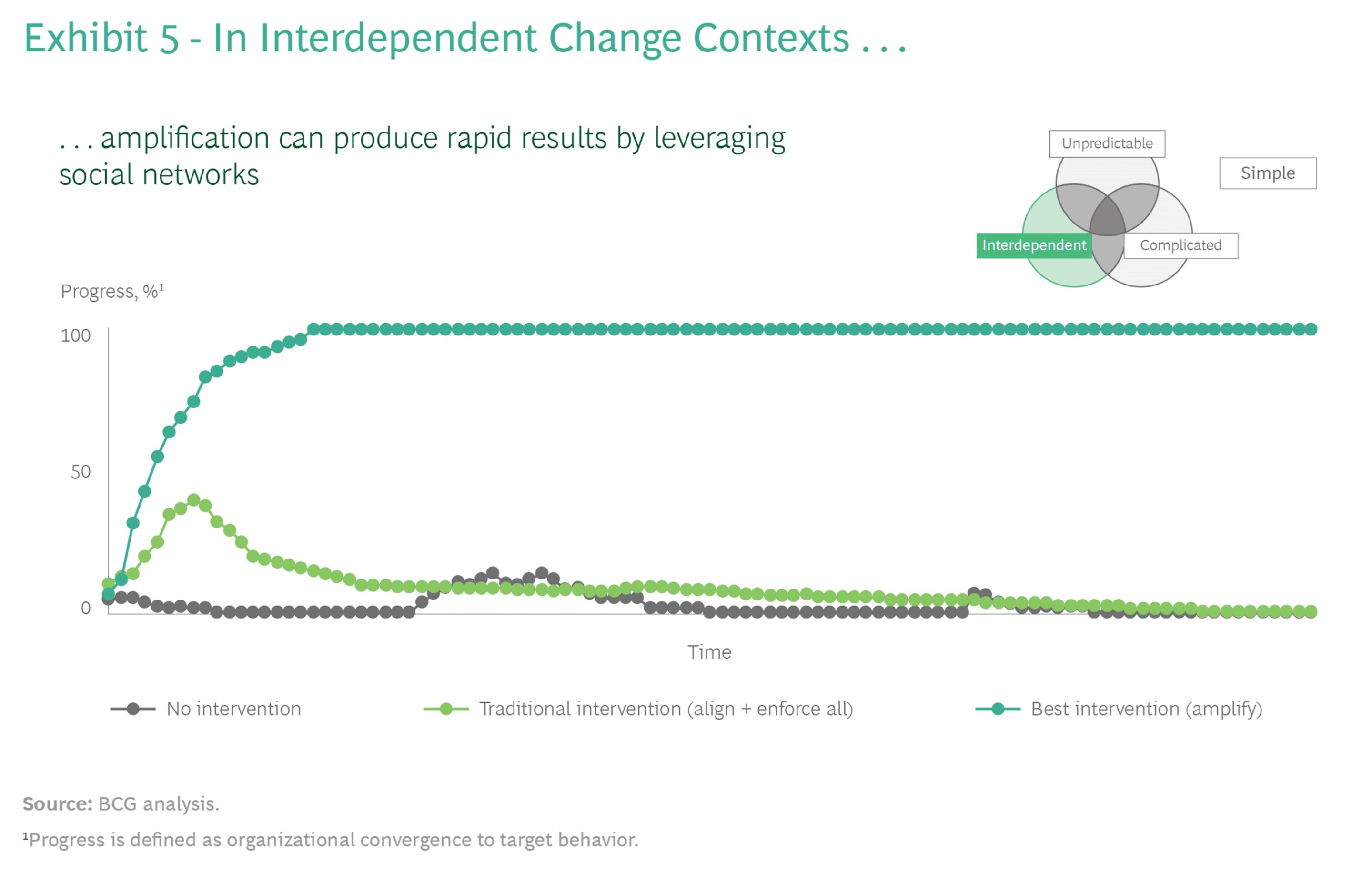

Interdependence. We next modeled our interdependent change context archetype, in which agents are connected through social networks and are disproportionately responsive to peer influence. These networks present leaders with an opportunity to leverage existing positive behaviors across the organization to create feedback loops that make others more likely to pick up such behaviors.

The best intervention to implement in this scenario is to identify agents who have already adopted the target behavioral traits and then amplify their influence, increasing the pressure on surrounding agents to match their behavior. As the number of individuals who adopt target behaviors increases so will the social pressure on others to converge on those behaviors, increasing its likelihood of spreading even further. Leaders must carefully choose which behavior to amplify, as networks of reciprocal influence can transmit and reinforce counterproductive as well as positive ones.

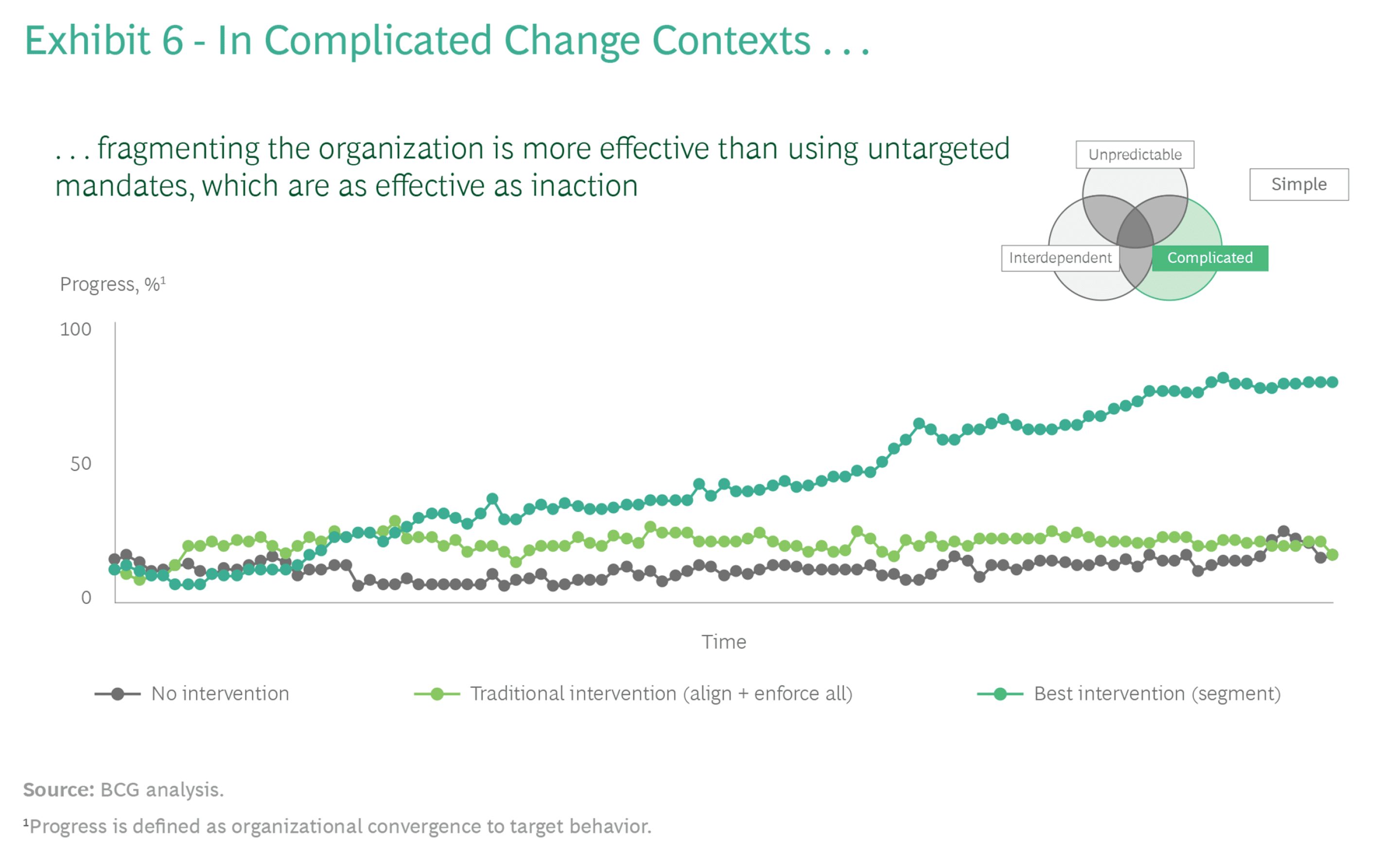

Complicatedness. Finally, we simulated complicated change contexts. These contexts are modeled as organizations in which each agent has a different target behavior, meaning that leaders cannot simply use a one-size-fits-all approach. Instead, leaders should segment the organization into smaller units which can then be given a set of standardized behaviors. To do this, leaders will need to target smaller groups of agents — or even individuals — to enforce the correct behavior.

This can be a lengthy process, as leaders must go through many additional steps to individually engage relevant groups. However, segmented enforcement is far more effective than untargeted mandates, as it enables the exploration of independent yet parallel strategies.

The change simulator illustrates the fact that the effectiveness of change interventions largely depends on the change context. No single change philosophy — not even traditional change management — works equally well in every case.

Furthermore, the simulator shows that though some contexts may be easier to affect than others, all contexts can be influenced through carefully considered action. For example, an unpredictable context may not respond well to direct intervention but can still be understood and influenced through incentivized experimentation. This can translate to real-world scenarios in which leaders should prioritize experimentation and decentralized learning over directives and mandates for unpredictable change efforts.

Building Your Change Toolkit

Even with a better understanding of the different change contexts, leaders may still tend to instinctively lean towards traditional change management methods. To avoid this, and to extract the full benefits of a context dependent approach, leaders can build a new integrated approach to change from the following elements.

Expand opportunities for change. The current reliance on stepwise, top-down planning may be due in part to the limited or overly simplified nature of the change efforts leaders are willing to undertake. Rather than only pursuing change in limited or comfortable circumstances, leaders should broaden their horizons and consider more challenging opportunities for change. Change opportunities may often become apparent through formal planning, but they can also be sparked by serendipitous observation or experimentation. Once leaders have expanded their view of what change is possible, they will be better able to conceive of and utilize more varied change interventions.

Deaverage large change problems. Often, leaders do not take the time to understand the different parts of the change effort. To tackle a large change problem, leaders must deconstruct the broader transformation effort into its component parts, each of which has unique and diverse traits and will respond to different interventions. These parts can include different change goals or different groups within the organization and, consequently, may call for different interventions. By understanding the differences between components, leaders can avoid the indiscriminate and uniform application of change interventions that may not work equally well across components.

Probe to better understand the change context. Once leaders have a sense of the different components of their transformation effort, they can implement quick, probing actions to test their context, such as deploying pilot initiatives among limited segments of the organization. These probes can provide insight into and confirmation of the change context.

Match the change philosophy to the change context. Once leaders understand the various features of their change context, the next step will be to recognize the associated roadblocks they are likely to face — and the interventions that will drive their success. These interventions should be articulated as part of a change philosophy that fits the change context in question. For example, if a leader recognizes that their change context seems to be both large in scale and heterogenous, they will know to implement the Transforming for Simplicity change philosophy rather than relying on traditional, static change management interventions.

Master a wide range of tactical interventions. As leaders select and deploy an appropriate change philosophy, they will be able to identify specific interventions to apply to their current situation. However, change contexts themselves change over time — especially as change efforts succeed in reshaping an organization. Therefore, leaders need to remain flexible and be ready to adapt their change philosophies. As an example, rather than relying on a single tactic, Continental Airlines was able to successfully implement multiple strategies based on the needs of the organization. The culture was changed by (1) replacing previous officers with new individuals, (2) developing a new incentive for employees to improve on-time performance, (3) implementing a plan to improve customer service through city assignments for leaders, (4) improving communication among employees, and (5) centering the new culture around employee engagement and company pride. To ensure an expanded understanding of potential solutions, leaders should conduct broad cross-industry research to identify relevant precedents and creative interventions, rather than just relying on planning or personal experience.[10]https://hbr.org/1998/09/right-away-and-all-at-once-how-we-saved-continental

Leverage workplace analytics to observe progress in real-time and adapt. By using data rather than just instinct or lagged, subjective reporting, leaders can better understand the change context and fine tune interventions accordingly. Once leaders have selected a set of interventions, clear and effective tracking processes can help monitor the impact of their chosen tactics. These can include project management software, network mapping software, and regular pulse-check surveys, each of which can provide input on change progress and stakeholder buy-in and satisfaction. AI and analytics can be used to better mine complex patterns in the output from these assessments to provide detailed insights on the status of the change effort, influencing how leaders tune interventions going forward. Organizations like pymetrics can provide workplace analytics that leaders can use to assess and design their change interventions.

Not all change efforts are created equal and therefore success requires expanding the change toolkit well beyond the standard methods of traditional change management. With a new appreciation for the diversity of the change contexts they might face, leaders will be better equipped to adopt the right change philosophies to shape the future of their organizations.