In 2024, eight of the ten most populous countries in the world held general elections. Yet, according to recent reports, democracy is increasingly fragile: The Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Democracy Index report for 2023 concludes that “democratic backsliding continues”, while the University of Gothenburg’s V-Dem Institute finds in its 2024 analysis that “almost all components of democracy are getting worse in more countries than they are getting better.”

While some corporations have thrived in non-democratic regimes, backed by a central authority, capitalism generally rests on the foundations of a strong democracy – such as fair, transparent, and predictable enforcement of the rules, as well as high levels of consumer confidence. Conversely, the prosperity and growth delivered by capitalism provide the economic security and independence that sustains democratic institutions. As such, democracy and capitalism are co-dependent.

What, then, can businesses do to counteract the increasing fragility of democracy – and sustain this foundation of their success?

At our 2025 Meeting of Minds, we assembled a group of leading thinkers to better understand the problem of democratic fragility, identify its root causes and implications, and outline how businesses can navigate and support fragile democracies.

The participants included:

- Delia Baldassarri, Julius Silver, Roslyn S. Silver, and Enid Silver Winslow Professor in the Department of Sociology at New York University,

- Lee Drutman, Senior Fellow in the Political Reform program at New America,

- Thomas J. Friedman, author, reporter, and “Foreign Affairs” columnist at the New York Times,

- Kirsty Graham, CEO of Edelman US,

- Georg Kell, Founder and former Executive Director of the United Nations Global Compact and Chairman of Arabesque Group,

- Hélène Landemore, Professor of Political Science, Yale University,

- Nikolaus Lang, Global Leader of the BCG Henderson Institute and Managing Director and Senior Partner at BCG,

- Patrick Langrell, Director of the Governance and Public Affairs Centre at Australian Catholic University,

- Michael Lenox, Tayloe Murphy Professor of Business Administration, University of Virginia, and Professor of Public Policy at the Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy,

- Simon Levin, James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University,

- Eric Maskin, Adams University Professor of Economics and Mathematics at Harvard University and recipient of the 2007 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics,

- Scott C. Miller, director of the Miller Center’s Project on Democracy and Capitalism and an assistant professor at the Miller Center, University of Virginia,

- Karthik Ramanna, Professor of Business and Public Policy at the University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government,

- Martin Reeves, Chairman of the BCG Henderson Institute and Managing Director and Senior Partner at BCG,

- Sam Wang, Professor of Neuroscience, Princeton University, and founder of the Princeton Election Consortium and Princeton Gerrymandering Project.

This article summarizes key elements of our discussion, which we hope will help corporate leaders improve their understanding of and ability to navigate democratic fragility.

Towards a more nuanced understanding of democratic fragility

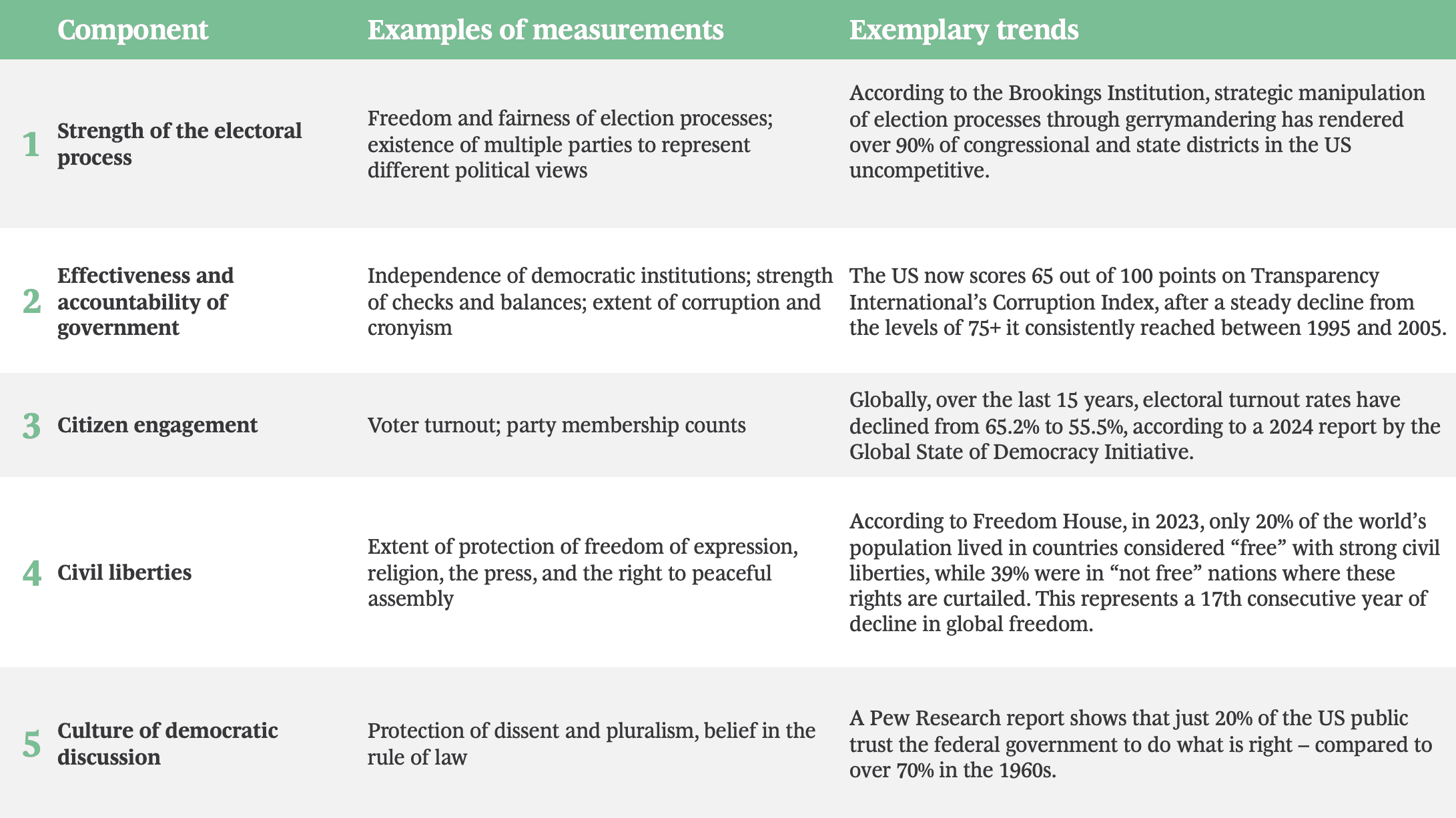

Our discussions brought about a more nuanced understanding of democratic fragility. In table 1, we summarize the core components of a democratic system, some of the measures by which they can be assessed, as well as exemplary trends that illustrate increasing democratic fragility.

Table 1:

Sources: Brookings Institute and Ismar Volić; Transparency International; Global State of Democracy Initiative; Freedom House; Pew Research Center

Leading analysts, such as EIU and V-Dem, use measures including those outlined in table 1 to score the strength of democracies around the globe. They find that democratic fragility is steadily increasing: According to EIU’s most recent report, the global democracy index has fallen to the lowest level since measurement began in 2006. The V-Dem Institute, meanwhile, finds that the level of democracy enjoyed by the average person is back to 1985-levels.

This trend is widespread across the globe. However, it is not uniform: Democracy is becoming increasingly fragile not only in newer, less established democracies (like some members of the former Eastern bloc), or countries that were still transitioning towards democracy (like Myanmar), but is also occurring in some long-established democratic strongholds.

On the other hand, some countries are becoming increasingly democratized – including Benin and Montenegro. However, these are relatively few (less than 20 countries score meaningfully better than in previous years in either the EIU or V-Dem reports) and are almost exclusively very small countries in terms of population size. Finally, some places remain classified as democratic strongholds, including many countries in Western and Northern Europe, particularly Scandinavia, as well as countries like Canada, New Zealand, and Japan. However, in some of these places – such as Germany or France – there has been increasing civil unrest (for example, the Yellow West movement in 2018-2019 and protests against pension reforms in 2023) as well as a surge in popularity of extremist parties.

Root causes of increasing democratic fragility

The discussions at our Meeting of Minds underlined that there is no single root cause of increasing democratic fragility – but rather a complex network of interconnected factors.

Economic factors: Wealth and income inequality – which have significantly increased in many parts of the world – drive the outsized political power of elites. Moreover, they contribute to social polarization, sharpening the divide of the wealthy vs. non-wealthy classes. This, in turn, has caused public backlash – sparking, for example, anti-elite movements in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

Economic inequality also manifests itself in divergences in opportunities – evidenced, for example, by the strong correlation between academic success and household income. This is also apparent in declines in social and intergenerational mobility. The ability of individuals to pursue economic success – and to rise, both within societies and across generations – without being tied to inherited status (or political power) supports democratic principles – and its erosion drives increasing democratic fragility. The digital revolution has contributed to this problem by enabling one worker to do the jobs that ten or more would have conducted previously – leading to a concentration of success within a few superstar employees, while many others are left behind. The rise of GenAI is now set to supercharge this trend – driving increasing economic anxiety. As a result of these developments, less than one third of people in many advanced countries now believe that the next generation will be better off than the current one (US: 30%; South Korea: 24%; UK: 17%, Japan: 14%; Germany: 14%, France: 9%).

Consequently, there is a desire for disruption – a shake-up of the system – among the electorate, which creates fertile ground for populist rhetoric. In Europe, the level of support for populist ideologies is now at 27%, a historic high, which has been maintained since 2019. Perhaps even more alarmingly, a recent survey by Edelman shows that 53% of 18-34 year-olds see hostile activism (incl. damaging property or committing violence) as a viable means to drive change.

Geopolitical factors: After decades of increasing globalization, protectionist tendencies are now on the rise, driven by the perception that others are unfairly benefiting from the economic success of one’s own country. This is further enabling populism, which leverages simplistic, us-vs.-them rhetoric.

A further geopolitical factor are the mass migration flows observed around the world – which, while in many cases driven by war or prosecution, are also often motivated by the desire of migrants to achieve more economic security for themselves and their families. Mass immigration not only provides further ammunition for populist policies, but also puts pressure on social security systems as well as public or health services – further contributing to economic anxiety and feeding populism.

Social factors: A lack of economic equality and opportunity is driving perceptions about a lack of fairness of the system – a “rigged game”. This is bolstered by instances of (actual or perceived) corruption or nepotism. The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer provides evidence for this, showing that 61% of people hold grievances against business, government, and the rich because of perceived unfairness (or the “selfishness of the wealthy”).

In parallel, roiling culture and identity wars, and the associated moral outrage, are further driving social polarization. This is manifesting itself along political party lines: In 1960, 4% of US Republicans and Democrats said they would be unhappy if their child married someone of the opposite political party – by 2019, this had risen to 45% of Democrats and 35% of Republicans.

This is also tied to an increasing coarseness of political discourse: The language used in congressional speeches has increased in emotionality and intensity over the past fifty years.

A further cause of democratic fragility is the erosion of meso-institutions, which bridge the gap between the highest levels of political power – at the national level – and individual preferences expressed at the local level. In particular, a lack of opportunity to engage directly in political life – for example, via local parties, unions, or associations – is leading to a disconnect from larger power structures: In the US, so-called fraternal associations – like Rotary Clubs, Jaycees, Lions, or Civitans – all experience significant decreases in membership numbers. Attendance of religious services has fallen sharply across faiths over the past decades. Union membership in the private and public sectors has been in decline for many years, and has now reached levels predating the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. The resulting lack of opportunity for face-to-face deliberation at the local level also means forgoing an opportunity to counteract polarization.

A related development is the death of local newspapers: A recent study by the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University found that in 2023, the loss of local newspapers accelerated to an average of 2.5 per week. More than half of all US counties now have limited access to reliable local news and information. As a result, local issues remain underreported and highly polarized views, which may otherwise have been filtered or buffered by a sense of local community and mutualism, proliferate: A local newspaper is less likely than a national station to go too far to one extreme or another because its owners and editors live in the community and know that for their local ecosystem to thrive, they need to preserve and nurture healthy interdependencies. The erosion of meso-institutions leads to a centralization of power at the top, resulting in the alienation of the electorate.

Technological factors: Another driver of polarization and mistrust is the scarcity of non-biased information. According to a Gallup survey, only 31% of Americans trust the mass media to report the news fully, accuracy, and fairly. Believing large media houses to be partisan, the public increasingly turns to social media for information: 20% of Americans get their news from influencers and creators, with Gen Z being over-represented. However, these creators often operate independently, lacking editorial oversight. They also may be incentivized to sensationalize or even misreport news by social media algorithms, which prioritize engagement over accuracy.

Finally, echo chambers as well as filter bubbles created by social media platforms are believed by experts to amplify extreme views and contribute to the spread of misinformation or disinformation.

Electoral system factors: The experts at our Meeting of Minds highlighted that beyond the external factors driving increasing democratic fragility, shortcomings of the electoral and governance system are also partially to blame. Underlining this are recent findings from Edelman’s Special Analysis on Trust and Government, indicating that only about half of respondents in democracies with recent or upcoming elections believe that their governments were fairly elected and legitimate (Germany: 61%, US: 55%, UK: 53%).

For one, the electoral systems we use results in a poor representation of preferences. This is specifically the case in countries with a first-past-the-post electoral system – like the US –, which leads to a winner-takes-all outcome, whereby often a slight majority gains outsized influence. More generally, a key issue is that political preferences are being captured in low dimensionality – essentially, people can only express their desires along the axis of liberal vs. conservative. Voters with more complex views become trapped inside major parties and a large proportion of the electorate is silenced – not only centrists, but anyone whose opinions are complex or multi-issue.

Poor representation is also evident in the composition of legislative bodies: In short, representatives are not representative of society. For example, 96% of congress members hold a college degree vs. 45% of the general population. Even more stark is the difference for secondary degrees (such as JD, MD, or MBA), which 75% of senators hold, compared to 13% of US adults. Finally, more than half of Congress members are millionaires. This reflects the outsized influence of elites, as well as a lack of democratic inclusion of low-income and low-education groups.

Finally, our discussants suggested that undue election and legislative influence of non-democratically legitimized individuals or corporations – due to lobbying, campaign donations, or via the formation of special interest groups – drives misalignment between the preferences of the electorate and policy outcomes.

The vicious cycle of increasing democratic fragility: Many of the aforementioned factors result in reduced government effectiveness: For example, governments may be unable to form or persist due to lack of a clear mandate, or legislative gridlock may arise due to unwillingness to conduct trans-partisan projects or even enter into discourse or agree on what the facts are.

This, in turn, inhibits governments’ ability to solve grand challenges like climate change, demographic aging, or the regulation of new technologies – breeding further dissatisfaction, apathy, and loss of trust among the electorate. As a result, discontent with democracy is at the highest level globally since 1995, also evidenced by the fact that since 2017, there have been significant anti-government protests in 147 countries. Trust in the government sits at 52%.

The implications of fragile democracy for business

As the vicious cycle of democratic fragility unfolds, a move towards autocracy may ultimately lead to an inability of citizens to hold governments to account, and to a curtailment of personal freedoms as well as civil liberties.

The fragility of democracy also affects business: One key driver of the success of corporations over the past century is that most democracies have embraced economic growth as a goal, aligning the interests of governments and firms – for whom this has meant subsidies, tax incentives, a limiting of government intervention or bureaucratic overhead, public investments in crucial infrastructure, and the fostering of competition (for example, through anti-trust interventions).

While autocratic governments may also embrace or look to foster economic growth by similar means, our discussions highlighted many further ways in which business depends directly on the foundations of democracy.

At the most basic level, the existence of a legal framework (for example, protecting contracts and (intellectual) property) is a foundation for business dealings. The fair and consistent enforcement of that framework is key to business success: To achieve long-term prosperity, companies need an impartially refereed game – an equal playing ground, without favoritism or cronyism. The absence of fairness results in costs – of having to “buy” favor, or of managing mistrust among competitors or collaborators. Similarly, the absence of consumer or worker protections results in mistrust and frictions with these groups.

The relative stability of democratic governments is conducive to predictability, enabling long-term economic planning. Moreover, democracy is characterized by free speech, which enables the spreading (and recombination) of ideas, fostering innovation. The decentralization of power in democracies also allows businesses to engage with local or specialized authorities, enabling them to benefit from targeted policies or incentives. Finally, cooperation between (democratic) governments around the world creates opportunities for international expansion or talent access.

Evidence suggests that democracy has significant positive impacts on economic growth: Countries that transitioned from non-democracy to democracy between 1960 and 2010 saw increases of 20-25% to GDP per capita in the 25 years after their transition.

How businesses can navigate and support fragile democracies

Given their dependence on the foundations of democracy, it is in the interest of business to counteract democratic fragility. And businesses are positioned to have a positive impact: The power and influence of large corporations rivals those of many nation states; businesses remain more trusted than government institutions; and the transnational nature of many corporations gives them the ability to act as international diplomats and changemakers.

Our discussions at the Meeting of Minds highlighted four principles which businesses should consider as they navigate and seek to support fragile democracies.

1: First, do no harm

First and foremost, firms should avoid unnecessary entanglement in political debates – not only because this regularly results in public backlash, but also to prevent distorting the democratic process. Entanglement can be justified only if an issue is directly connected to the core economic activity of a firm – making involvement legitimate and the business a competent contributor to the discussion.

Businesses should endeavor to legitimize their entanglement by adopting enhanced practices of social accountability. This means actively inviting stakeholders – including employees, suppliers, clients, and regulators – to scrutinize their chosen mode of engagement on the issue at hand. Moreover, it means that businesses should ensure that their involvement ultimately points to the appropriate democratic or regulatory forums for broader societal decisions.

After decades of entanglement, many businesses are now subject to enormous pressure from their stakeholders to “speak out” or “take a stance”. Reducing this pressure will require resetting expectations towards non-involvement by adopting institutional neutrality as an explicit policy and sticking to it for an extended period of time. The University of Chicago’s official stance to be the “home and sponsor of critics”, but not a critic itself is an example of this – and helped it to navigate recent US-wide campus protests about the war in the Middle East better than many other universities.

Moreover, companies must actively fight corruption – which includes ceasing unethical lobbying practices. Corruption inevitably creates a race to the bottom for businesses, necessitating ever greater “investments” to level the playing field vs. competitors. Our discussants at the Meeting of Minds agreed that lobbying should be confined to sharing knowledge. Furthermore, ethical lobbying practices should be adopted. One framework to guide this are the Erb principles for Corporate Political Responsibility, which include providing unbiased and evidence-based information to legislators as well as being transparent to all stakeholders about one’s political activities.

Furthermore, companies should articulate principles that address ethical, social, and political issues. These principles should be specific enough to guide choices, be applicable across different contexts, and be easily auditable: For example, “never commit or condone bribery” or “advance technology broadly by open-sourcing patents”. To develop such principles, companies must understand how social or political issues might intersect with their business. Then, they must engage employees in the development of these principles, to anticipate potential challenges early. Finally, it is crucial that a company’s principles do not just remain theoretical: For example, clothing company Patagonia lives its mission of “saving our home planet” by taking steps like donating 1% of sales to environmental nonprofits, and placing ownership of the company in a nonprofit trust that ensures all profits not reinvested in the business are used for sustainability causes.

To enable navigating a fragile political environment, companies also need to build a corporate affairs “muscle”. Digital technology has dramatically increased the amount of scrutiny that any corporate actions and communications are subjected to. This is exacerbated by the reach social media has given to individuals – whose criticism of corporations can spread rapidly and widely.

As a result, the speed with which corporations have to react to new developments has increased: Put yourself in the shoes of a corporate affairs leader, tasked by their CEO to come up with a response (or justification for non-response) when a political leader “tweets” a new policy proposal, or when a political activist with large social media following calls out a company’s practices. With the intersection of marketing, policy, and communications becoming ever more fraught, building out the necessary public affairs expertise is crucial.

2: Be a uniting force

In a polarized world, business can be a uniting force, counteracting one of the root causes of increasing political fragility – we may no longer bowl together, but we still work together. For one, businesses can promote intergroup cooperation through shared, apolitical interests: For example, corporate volunteering and projects with common social goals can help unify employees with different views. Moreover, corporations can create forums for cross-group dialogue and foster healthy engagement by setting clear rules for respectful discussion on difficult issues (like Cisco’s comment “color spectrum”) – embracing reasonable disagreement rather than “us vs. them” viewpoints and escalatory language. Finally, businesses can reshape the narrative towards long-term, trans-partisan challenges, creating common ground.

Another way of moving towards greater unity is forming coalitions – for example, to establish systems of mutual accountability or coercion among businesses: Patagonia co-founded the 1% for the Planet initiative, encouraging businesses to donate 1% of their revenue to environmental causes. There are now ~5,000 businesses in this network across 110 countries, that have already collectively given ~700 mn USD. Alliances can also be formed with actors beyond the business realm – such as policymakers, academia, and civil society – for example, with the goal of addressing emerging technologies: In 2020 the Israel Ministry of Transport (MoT) adopted an innovative process in developing a regulatory framework for the commercial deployment of autonomous vehicles. The MoT engaged a wide range of stakeholders, including industry leaders like Cruise, Waymo, and Zoox, academics, and non-profits. They also formed cross-ministerial partnerships, sharing best practices with other local and global regulators. Beyond their immediate benefits, such coalitions also foster trust among participants: By collaborating on topics on which there exists common ground, more divisive issues that emerge in the future may become easier to tackle.

3: Take your role as “provider” for your workers seriously

A further key role for business in addressing the root causes of increasing democratic fragility is to provide economic safety and opportunities. According to a 2025 report from Edelman, respondents feel overwhelmingly that business has to take seriously two issues: Providing well-paying jobs in local communities and training or reskilling employees so they remain competitive in the labor market. One way of accomplishing this is to embrace vocational training programs – common in countries like Germany and Austria – that equip workers with marketable skills without requiring them to finance a college education.

Our discussants also noted that empowering workers – for example, through co-determination models (such as ensuring worker representation on the board of directors of public companies) – can be a powerful tool for not only ensuring that workers’ voices are heard, but also for driving broader political engagement.

4: Supplement cracks in democracy

To supplement the cracks in our democracies today, companies can promote non-partisan civic engagement, for example, by protecting employees’ rights to vote (or by giving employees a day off to vote) and engage in political discourse as private citizens. Moreover, businesses can champion facts and science, for example, by ensuring their communications are grounded in facts, by actively working against the spread of false information (e.g., by debunking myths), and by partnering with trusted experts. Finally, business leaders are called upon to lead by example when politicians don’t, i.e., to demonstrate and live by moral values.

Potential remedies beyond the realm of business

At our Meeting of Minds, we also discussed broader reforms of electoral or democratic systems that may have a role to play in addressing the fragility of democracy. Participants suggested a variety of options – from ranked-choice and Condorcet voting mechanisms that may reduce polarization; to proportional representation, which may increase political pluralism; to sortition and citizen’s assemblies, which may improve the representation of non-elites as well as engender more deliberation. Participants highlighted the importance of modeling the effects of such changes to be able to make predictions about what impacts they may produce, and to optimize the timing and sequencing of their introduction.

Crucially, these types of reforms are beyond the realm of business influence. Discussants at our Meeting of Minds agreed that corporate leaders should remain humble on their engagements with the fundaments of democracy.

Democracy is inherently fragile. This is not a transient phenomenon, but rather results from the need to actively foster trust in institutions, protect minority rights, and ensure a shared understanding of constitutional norms. The fragility of democracy is increasingly on display as many countries around the world trend towards autocratization.

However, this fragility is also a source of strength – keeping democracy dynamic, accountable, and open to renewal. The need for constant vigilance can drive citizens and businesses to participate more actively, encourage necessary institutional reforms, and foster a civic culture grounded in dialogue and compromise.

Given their dependence on the foundations of democracy, businesses must play a part in supporting it. Our Meeting of Minds highlighted key steps towards this end, from avoiding unnecessary entanglement and lobbying that may weaken democratic institutions, to counteracting the root causes of democratic fragility, such as polarization and economic anxiety.