Language reflects social reality. For example, the language of the Himba tribe in Namibia has distinct terms for various shades of green, because distinguishing between these shades is crucial in an environment where plants and their conditions are important for survival. Conversely, the Himba language has no separate words for blue and green—instead, a single term encompasses both colors, reflecting the lack of importance of this distinction in the daily lives of the Himba.

Language adapts not just to the environment, but also to the specific situation: We speak differently to colleagues than to friends—more formally, more precisely, and leveraging industry jargon. But to what end? In other words, what does the language of business reflect about the social reality of corporations?

This article uses language to delve into the corporate soul. Finding it to be impoverished in certain respects, we discuss what has caused the narrow focus of corporations on the functional. Then, we explore how to reshape corporate reality toward the humanistic—which we show will be needed to unlock competitive advantage.

Peering into the corporate soul

To peer into the corporate soul, we analyze the frequency and relationship of semantic clusters in a representative set of texts from business and everyday life. To this end, we selected texts that were rich in depth and unrestricted in their focus—and thus likely to include the topics that the speakers or authors determined as important. For the language of business, our choice was transcripts from earnings conference calls—open-ended and semi-formal conversations between senior leaders and investors. They reflect an attempt by a company to understand its status quo, aspired future, and place in society—transmitting this back to its audience with greater breadth and fewer constraints than we see in other sources of business texts (for example, annual reports or tweets).

For everyday texts, we chose to analyze posts on the social media platform Reddit, as well as transcripts from shows and interviews on National Public Radio (NPR). We felt that these similarly reflect the status quo, reactions to events and ideas, as well as future aspirations.

Across all texts, we collapsed the word variants down to their stems (for example, playing, playful, and played collapse down to play) and then further grouped semantically related word stems together, leveraging a large language model supplied by OpenAI. Simplistically, this can be thought of as creating synonym clusters, grouping together terms by common meaning and relationships (for example, play, explore, divert, cavort), to give an aggregated and digestible view of how often we observed a concept in a certain piece of text (for details, see the sidebar: Our methodology).

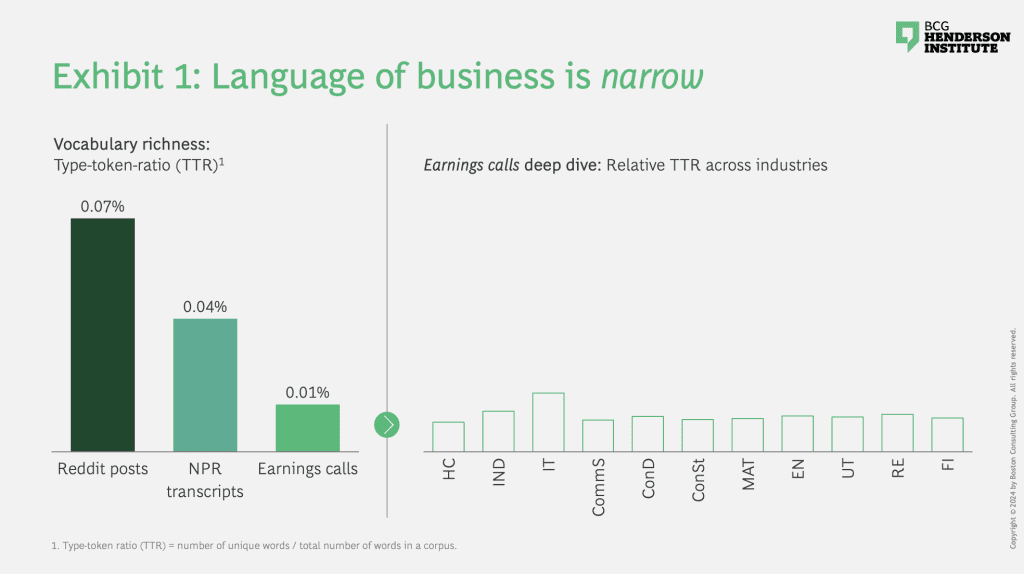

Our analysis reveals that the language of business is characteristically narrow—with the richness of the vocabulary in an earnings call being many times lower than in our proxies for everyday language: four times lower than that in a radio show, and seven times lower than in a social media post (see Exhibit 1).

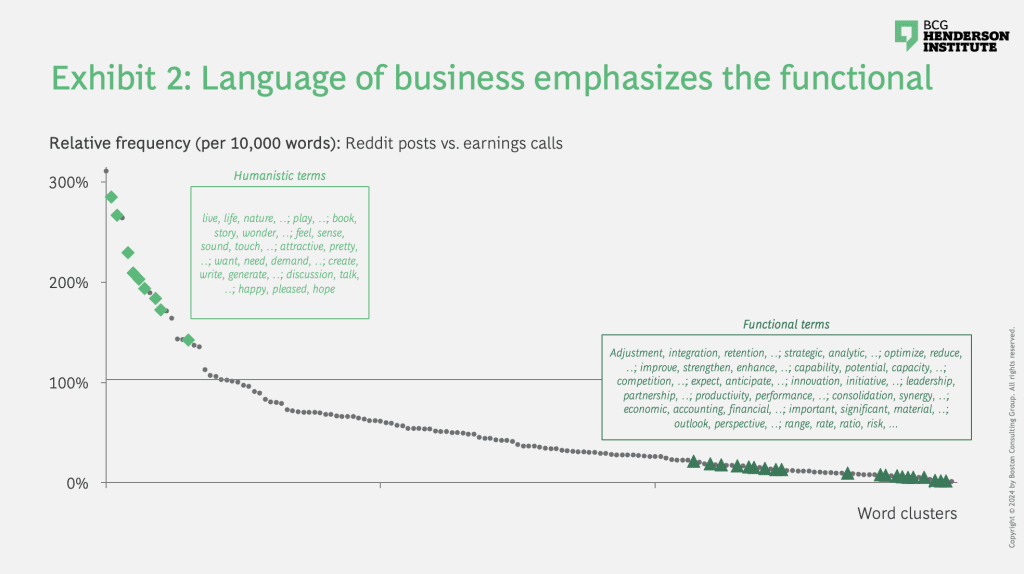

Moreover, the language of business leans toward the functional—with terms revolving around strategy (outlook, competition, initiative, and capability), management (optimize, diagnose, and synergy), financials (economic, accounting, and ratio), as well as leadership and innovation being significantly more common than in everyday language (see Exhibit 2).

Meanwhile, terms related to the human experience—emotions (happy, hope, and feel), creativity (create, write, play, and story), and aesthetics (attractive, nature, and wonder)—are underrepresented in business language, relative to the language of our daily lives.

What the language of business reveals about the corporate soul

This narrow and functional language has its roots in the era of industrialization, which gave rise to scientific management, a discipline aimed at maximizing efficiency toward its scientific ideal: this entailed, famously, breaking processes down into small steps that could be repeated, monitored, and, over time, optimized by management. The meticulously designed 84-step construction process of Ford’s Model T is an emblematic example of this.

Standardization did not stop at the workflows, but also extended to the expectations the company had of its workers: As Frederick Taylor, the founding father of scientific management put it: “In our scheme, we do not ask for the initiative of our men. We do not want any initiative. All we want of them is to obey the orders we give them, do what we say, and do it quick.” This, in turn, was also reflected in language: Company-specific language was developed that would strengthen conformity and enable the quick integration of new joiners. And efficient communication, leveraging a narrow and task-oriented vocabulary, was emphasized over language that would foster human expression or creativity—which is reflected in our analysis.

In summary, this new approach to management prioritized the functional value of the workers over their broader human value. Said Taylor: “In the past, the man has been first, in the future the system must be first.”

The success and limitations of scientific management

Make no mistake: The introduction of scientific management was successful. After its adoption, the time it took to produce Ford’s Model T fell from 12 to three hours in the span of a few years. And, due to its success, this new management approach soon spread beyond the production floor to the corporate offices—infusing itself into the company ethos across industries, ultimately driving a century of productivity gains.

However, scientific management also showed its limitations from the beginning: on the production line of the Model T, employee turnover and absenteeism soared—driven not only by high production quotas and repetitive tasks but also by the apparent preference of humans to work in humanistic environments, rather than scientific systems.

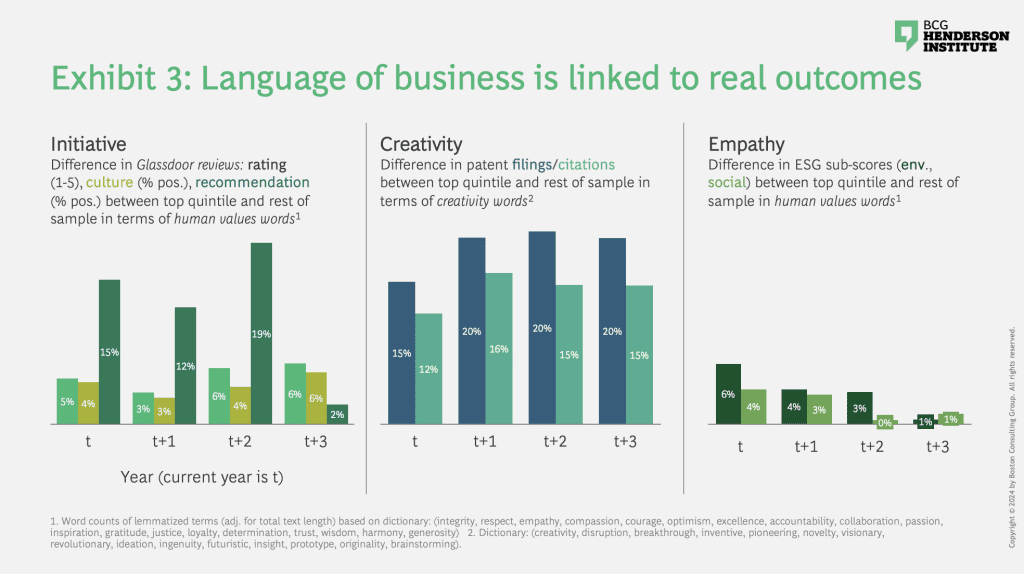

Today, with surveys showing consistently that less than a third of workers feel engaged at work, it seems that goals, quotas, bonuses, and sanctions remain insufficient motivators of human initiative. Language plays a role, too, with a functional vocabulary constraining authentic self-expression—which has been linked to how engaged we feel at work. Our analysis corroborates this, showing that firms whose language incorporates more terms associated with human values and emotions (for our methodology and the dictionary we used, see sidebar: Our methodology) have more engaged employees. The top quintile achieves ~3% to ~6% higher Glassdoor review scores for overall rating and culture, and ~12% to 20% higher likelihood of the workplace being recommended to others, than the mean of the rest of our sample (see Exhibit 3).

Moreover, the rise of knowledge work has meant that there are fewer standardizable tasks, and much of what standardized work remains could increasingly be outsourced to robots and AI. As a result, human work will increasingly rely on creativity—which is not a skill scientific management was designed to encourage. Rather, a narrow vocabulary constrains what we think about: our analysis shows that companies that use more creative language achieve better innovation outcomes, with the top quintile filing ~20% more patents and getting ~15% more citations on these than the average firm in the rest of our sample.

But the stated goal of corporations has changed, extending beyond the achievement of maximum efficiency to driving growth through innovation and contributing to solving humanity’s biggest problems. This requires grasping problems and opportunities in terms of human needs and values, as well as striking the right balance in decision-making between tackling social or environmental issues and achieving short-run growth and profitability. In other words, it requires a degree of empathy. This, again, can be tied to the language of business, with our analysis showing that companies which use words associated with human values and emotions also achieve superior environmental, social, and governance (ESG) ratings: the top quintile achieves between ~3% and ~6% higher scores on environmental and social dimensions than the average firm in the rest of the sample.

We recognize that it would be naive to think that language alone is driving under- or outperformance on these metrics. Language can also be thought of as merely a barometer of corporate culture—a window into the soul. Still, these findings tie the corporate soul to competitive advantage—which depends on recognizing societal or environmental problems, developing creative solutions, and having an engaged workforce to execute them.

As such, we argue that it is high time for businesses to go beyond scientific management and toward a humanistic management approach that emphasizes initiative, creativity, and empathy.

Toward the humanistic corporation

Businesses have recognized this need—and the domain where the shift to a more humanistic corporation has been most vividly observable is language: for one, there is a trend toward inclusive language—be it through gender-neutral job descriptions, more accessible terminology in product descriptions, or greater cultural sensitivity in external communications. Moreover, there has been a widespread adoption of mission, corporate purpose, and values that tie the economic success of a business to its impact on the social and environmental context.

These trends may indicate an implicit belief on the part of business that language not only reflects but can also shape reality. Empirical evidence suggests that this may be the case. Returning to our example of the Himba people of Namibia, studies have shown that language affects perception: due to the lack of a term for blue in their language but having a wide variety of words for different shades of green, Himba people are slower than a control group of English speakers to identify the color blue in a lineup but faster at accurately discerning different shades of green. Similarly, corporations may be trying to speak into existence a positive social or environmental impact—or at least a heightened awareness of these issues.

However, there are limits to the power of language. In particular, there is the very real danger that it is only the language that changes—and not the underlying reality. Like in George Orwell’s novel 1984, the language can become a lie. This criticism is regularly levied at corporations whose words and actions appear to be disconnected.

To enhance agency, creativity, and empathy, language needs to be changed in congruence with the underlying social reality of the organization—that is, its structure and management. Below, we outline key imperatives to this end.

Initiative

1. Enable holistic ownership. While it may be efficient to parcel out tasks, this approach is unlikely to inspire employees—and may lead them to leave their best selves in the parking lot. To create the space for workers to take the initiative, enable ownership of whole problems, from inception to completion. In linguistic terms, this can be supported by emphasizing themes of ownership, responsibility, and identification: from Complete this task to Own this challenge, from Follow these instructions to Design your solution, and from This is part of your job to Your job shapes our success. For tasks that must be subdivided, develop narratives that show how all activities are essential parts of the whole, encouraging ownership and cohesion across the firm.

2. Align with excellence. Holistic ownership provides workers with a degree of freedom in how tasks are solved. Systems should then be set up to encourage employees to use their agency to go beyond expectations. This means reducing standardization, leaving room for individual discretion: from manager to creative designer to data scientist, moments of excellence and inspiration can only come when employees apply the best of their abilities, whether or not that means following the handbook.

Encouraging excellence also requires a new approach to goal-setting: Tactical goals are undoubtedly useful in many contexts, ensuring consistency and protection for near-term priorities. But by setting out the aim so definitively, they may hold employees back from going above and beyond—pursuing goals fueled by their curiosity and passion, rather than the expectation of immediate business value. Look no further than the great craftsmen and women, such as carpenters, architects, and potters, who, without prescriptive direction, conceive work that brings joy to many. For example, Apple’s key industrial designer, Jony Ive, watched his father work as a silversmith during his childhood, and reports that the hands-on craftsmanship process was an important influence. Language is crucial in this: dare to formulate infinite goals—leveraging indefinite, non-time-bound terminology, and tying outcomes to human values—treating tactical aims as an oblique outcome of the pursuit of excellence.

Creativity

3. Broaden the playing field. Encouraging ownership and striving for excellence will do their part in fostering creativity. Building on this, executives must broaden the playing field: in terms of structure, this may mean putting in place modular, cross-functional teams to increase collisions between individuals with different perspectives and ideas, generating opportunities for surprise, recombination, and collective intelligence.

Changes to language can support this: by abolishing jargon, you can tear down barriers to understanding and involvement, and enable more non-experts to be involved in creative ideation. This will help in developing innovative ideas—particularly solutions distant from the status quo.

Finally, broadening the playing field can mean expanding your vocabulary and employing analogy, which can help you see new possibilities. For example, various executives have garnered inspiration from science fiction works—not to borrow ideas from established worlds, but to immerse their teams in radically different, alternate realities, thus breaking the constraints of the present.

4. Encourage self-expression. In a world where growth is harder to come by than ever—due to encroaching ecological boundaries, a fading globalization premium, and higher costs of capital—developing creative solutions means harnessing the richness of human thought and emotion. Thus, enhance creativity by promoting self-expression through language, rather than mandating that workers stick to the corporate script: for example, Southwest Airlines encouraged flight attendants to inject anecdotes or songs into announcements—which have not only regaled customers but led to several “best place to work” awards.

Empathy

5. Tie your mission to human impact—and live it. Expressing aspirations and decisions in terms of human emotions and impacts is a crucial step toward enhancing consideration of social and environmental issues: for example, Patagonia has changed its mission statement from “Build the best product […]” to “We’re in business to save our home planet.”

However, companies must ensure that their purpose is not a hollow—or even deceptive—statement, but a guide to achieving true impact. To be done right, a statement of purpose should go beyond fostering engagement and garnering publicity, to informing business decisions. The purpose needs to be lived: in the case of Patagonia, this has meant taking steps like donating 1% of sales to environmental nonprofits, or placing ownership of the company in a nonprofit trust that ensures all profits not reinvested in the business are used to protect the planet.

The language of business reveals the lingering legacy of scientific management, which is ill-suited to modern corporate challenges. We propose imperatives for a new management agenda that emphasizes humanism over scientific ideals—combining changes in structure, management, and language.

Sidebar: Our methodology

Using natural language processing, we analyzed the frequency and relationship of meaning clusters in a representative set of texts from business and the everyday. We selected texts that were rich in depth and unrestricted in their focus and thus most likely to include the domains self-determined as important in the context.

For business texts, we utilized investor call transcripts (~2,600 earnings conference calls from 2019, from English-speaking companies across the world. For everyday texts, we chose chosen to analyze two sets: posts on the social media platform Reddit (~3,800 comments from posts on the Reddit forums AskReddit and IAmA (ask me anything), both focused on “general life” discussions), and transcripts from shows and interviews on NPR (~85,000 utterances—usually ranging between 30 and 150 words each—from NPR radio shows covering 20-plus years of NPR programs).

Across all texts, we collapsed the word variants down to their stems (for example, playing, playful, played collapses down to play) and then further grouped semantically related stem words together leveraging a large language model by Open AI. We also removed any so-called stop words (for example, at, but, by, for, if, it, of, such, that, the).

Equipped with these processed data sets, we conducted the following analysis:

- For Exhibit 1, we assessed the breadth of vocabularies by measuring the type-token-ratio (number of unique words versus total number of words in a corpus) in each set of texts.

- For Exhibit 2, we assessed the relative frequency (per 10,000 words) of semantically related word clusters in each set of texts.

- For Exhibit 3, we assessed the relation between business language and firm-level outcomes:

- Initiative: Difference in average Glassdoor review scores—overall rating (1 to 5), culture (% pos.), recommendation (% pos.)—for firms among top quintile versus rest-of-sample in terms of “human values” word usage—word counts of lemmatized terms (adjusted for total text length) based on dictionary: (integrity, respect, empathy, compassion, courage, optimism, excellence, accountability, collaboration, passion, inspiration, gratitude, justice, loyalty, determination, trust, wisdom, harmony, generosity).

- Creativity: Difference in average number of patent filings and citations (from Google Patents) for firms among top quintile versus rest-of-sample in terms of “creative” word usage—word counts of lemmatized terms (adjusted for total text length) based on dictionary: (creativity, disruption, breakthrough, inventive, pioneering, novelty, visionary, revolutionary, ideation, ingenuity, futuristic, insight, prototype, originality, brainstorming).

- Empathy Difference in average ESG sub-scores on environmental and social dimensions (from Arabesque) for firms among top quintile versus rest-of-sample in terms of “human values” word usage (same as above).

- Across the exhibit, we assessed the impact of word usage in a given year, as well as in the two subsequent years, to establish causality.