We enter the ’20s tipping into a new era for business, with new benchmarks for what constitutes a good company, a good investment, and a good leader. The defining expectation: good companies and investments will deliver competitive financial returns while helping society meet its biggest challenges, and in so doing enable sustainable business. Leaders with foresight and courage will use this dynamic to create new opportunities for growth, sustained returns for shareholders, and greater societal impact. It will take new ways of thinking, new modes of competitive advantage, deep and broad innovation in business models, and strategic engagement with full ecosystems. It will involve joining up the two currently disconnected uses of the “S-word” in business: sustainability and sustainable competitive advantage.

The ’20s will have significant implications for companies, capital, and capitalism. Here, we share our take on the emerging new era of business value, and the CEO agenda for value and the common good.

Why is corporate capitalism at a tipping point?

Stakeholders are beginning to pressure companies and investors to go beyond financial returns and take a more holistic view of how they impact society. This should not surprise us. After all, we have lived through two decades of hyper-transformation, where rapidly evolving digital technologies, globalization, and massive investment flows have stressed and reshaped every aspect of business and society.

As in previous industry transformations, the winners created new dimensions of competition and built innovative business models that brought increased returns for their companies and ecosystems. Many others found their businesses at risk of being disrupted, with familiar formulas no longer working. To meet the unwavering demands of Wall Street, they relentlessly optimized operating models, streamlined and concentrated supply chains, and specialized their assets and teams — leaving many less resilient and adaptable to shifting markets and trade flows. The resulting waves of corporate restructuring, consolidation, and repositioning have fractured company cultures and undermined their social contracts.

Furthermore, this hyper-transformation cascaded beyond individual companies and created socio-economic dynamics that left many people and communities economically disadvantaged and politically polarized. Combined with the increasing shared anxiety that the earth’s climate is changing faster than the planet can adapt, a global zeitgeist of risk and insecurity has emerged. We enter the ’20s with more citizens, investors, and leaders convinced things must change — and change quickly — in the way business, capital, and government work.

We now have no choice but to rethink the sustainability of the whole system against extreme externalities — or else we risk losing social and political permission for further progress. The 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) identify the moral and existential threats that we must meet head on. While some question their breadth and timeline, most agree that the SDGs, if achieved, would create a more just, inclusive, and sustainable world. Goal 17 calls for new engagement by companies and capital in partnership for collective action across the public, social, and private sectors. Five years into the SDG agenda, there is ample evidence that governments, investors, and companies are beginning to exercise their capacity to create much needed change.

Change is underway

Many institutional investors are racing to integrate ESG (environmental, social and governance) assessments into their decision making, and they are expecting companies to report on how they deliver on those metrics. New efforts promote radical disclosure, like the Bloomberg/Carney TFCD (Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure) that encourages signatories to report on the climate risks of their financial holdings. New standards initiatives are creating a foundation for non-financial performance accounting, with the possibility of widespread “integrated reporting” on the horizon. Companies are investing in “purpose” and defining their contributions to society against material ESG factors and SDG goals. Corporate sustainability and CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) functions, historically on the sidelines, are now being integrated into line business activity, with progressive companies expanding the scope of competition to include differentiation on environmental and societal dimensions. And through industry consortia, they are taking collective action on issues that both threaten their right to operate and open up new opportunities for their industries.

Such examples are important early signals that the context for business is changing. However, for all of the progress made on commitments, agreements, metrics and policies, sadly, there has been little aggregate progress against the top-level impact goals, like reducing CO2 emissions, cutting plastics waste, or narrowing social and economic inequality within nations. Without demonstrable impact and collective progress, social and political pressure will only build, further risking the legitimacy of corporate capitalism.

We expect a new societal context for business in the ’20s

Companies will face escalating social activism by investors, stakeholders, social mission organizations, and policymakers on issues of climate risk, economic inequity, and societal well-being. Governments and local communities will set a higher bar for “right to operate” and in a connected world a company’s local performance will quickly affect its global reputation and trigger social and regulatory consequences. Stakeholders will expect radical transparency on ESG performance. This will shift investor perceptions of a company’s risk and opportunity, skewing capital toward those that deliver both financial returns and positive societal impact. To satisfy a growing demographic of socially minded consumers and businesses, companies will need to demonstrate “good products doing good,” and anchor their brands and identity around a credible purpose. Talent will evaluate how authentic and attractive a company is by how it gives its employees a line-of-sight to making the world better, while providing a fulfilling career.

To win, companies will need to define competition more broadly, adding new dimensions of value through environmental sustainability, holistic well-being, economic inclusion, and ethical content. This will require radical business model innovation to enable circular economies for precious resources; provide assets that are shared rather than owned; broaden access and inclusion; and multiply positive societal impact.

Business is currently more trusted than government (according to the Edelman Trust Barometer) at this critical moment for corporate capitalism. Farsighted corporate leaders will see the opportunity for their industries to mitigate environmental and societal threats, catalyze collective action to discover new solutions, shape wider ecosystems, and expand trust with stakeholders. Such actions will be indispensable to strengthen social permission for corporate capitalism before it is further undermined.

Management will need a value and mission mindset

As in previous transformative eras for business, it will take a shift in managerial mindset to unlock new ways to win. We need a fundamental rewiring of managerial imagination and decision making, underpinned by a broader equation for corporate value that goes well beyond delivering a predictable P&L.

The starting point is “missional leadership”, which we define as instilling a driving and inspiring purpose that captures the broader ambition of the business beyond profit and gives employees meaning in their daily work. “Purpose” should not be a comforting and self-congratulatory statement of what the company already does, however — that would be an impediment to progress. Rather, it should define the aspirational societal contribution of a company based on its unique attributes, and inspire awareness of the broader context and progress towards business and societal value.

Armed with purpose, missional leaders promote a culture of curiosity and courage to stretch their business models in new ways, into their surrounding economic, environmental, and societal ecosystems. Knowing that such transformative thinking can be impeded by traditional metrics, which only tell us how to ascribe value, these leaders will work to change what we value. They will break from the tyranny of quarterly financial reporting by engaging investors and stakeholders on the company’s performance against a more balanced scorecard, demonstrating how the actions they take today will transform the business model, better positioning the company to deliver returns and social impact over time. They will think beyond designing their operations and organization mainly for efficiency, and thoughtfully engineer-in redundancy, diversity and flexibility for more resilient and adaptable businesses. And they will enrich their decision making by including staff with nontraditional business skills.

Winning in the ’20s will take management teams that both know the business and envision its larger potential to compete differently, with benefits for both shareholders and the common good.

CEOs need an agenda for value and the common good.

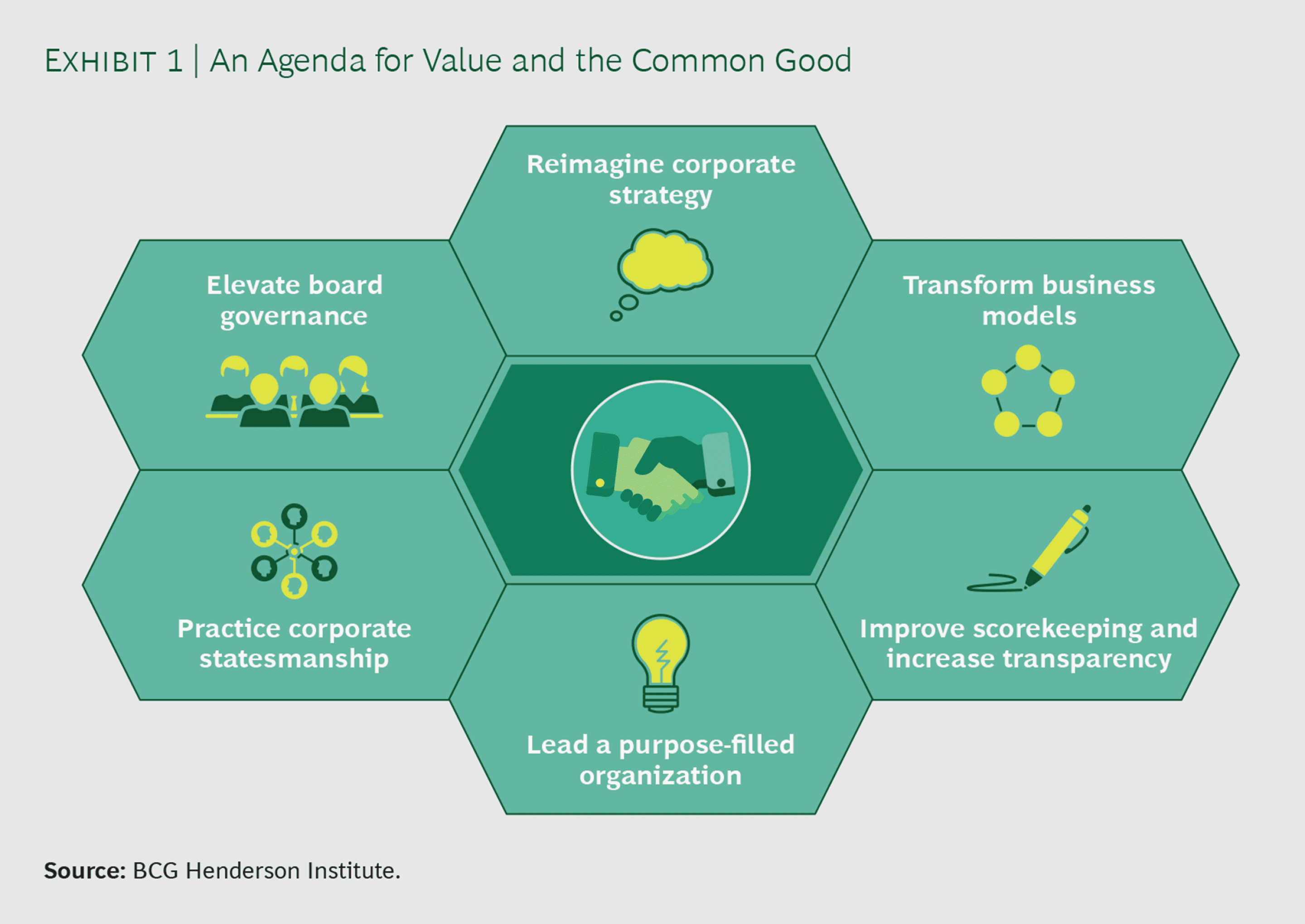

We frame the journey to new corporate value and the common good around six imperatives. It begins with reimagining corporate strategy, then involves transforming the business model, reframing performance and scorekeeping, leading a purpose-filled organization, practicing corporate statesmanship, and elevating governance. While challenging to execute, we argue this agenda for the 20s will be essential to create a great company, great stock, great impact, and great legacy.

1. Reimagine corporate strategy.

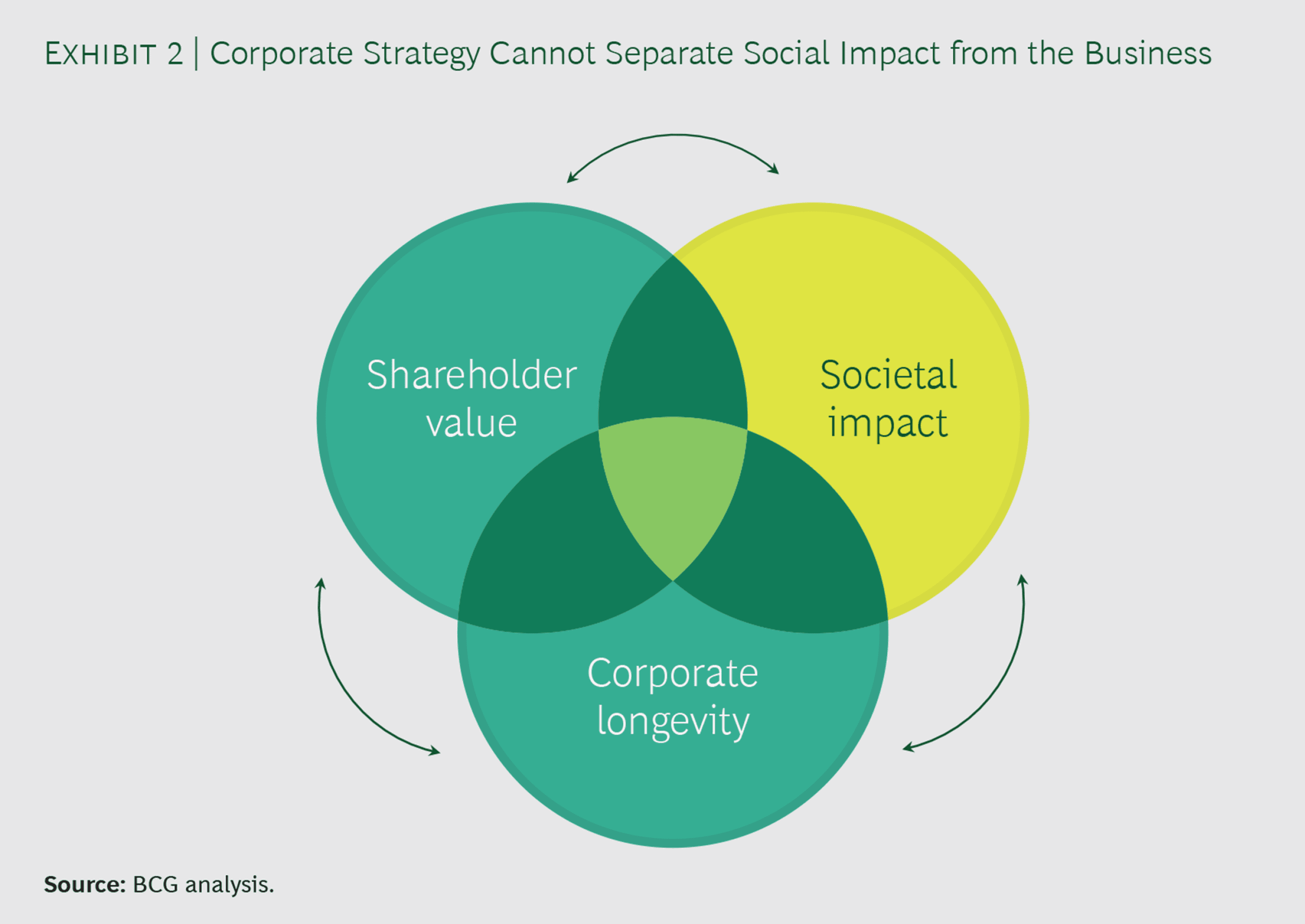

We believe few corporations have strategies ready for this new era of business. Exhibit 1 shows the ambition of corporate strategy fit for the ’20s. It establishes competitive advantage at the intersection of shareholder value, corporate longevity, and societal impact; the “quality” of strategy is thus judged by how it delivers both total shareholder returns and total societal impact.

Consequently, it widens the scope of competition to create rich multi-dimensional differentiation and relative advantage in several areas of societal value. It embeds societal content into new business constructs, shared value chains, and reconstructed ecosystems. It also opens, broadens, and deepens markets to enable access and inclusion. And it expands industry space by conceiving coalitions for collective action that solve existential risks to environmental and societal ecosystems.

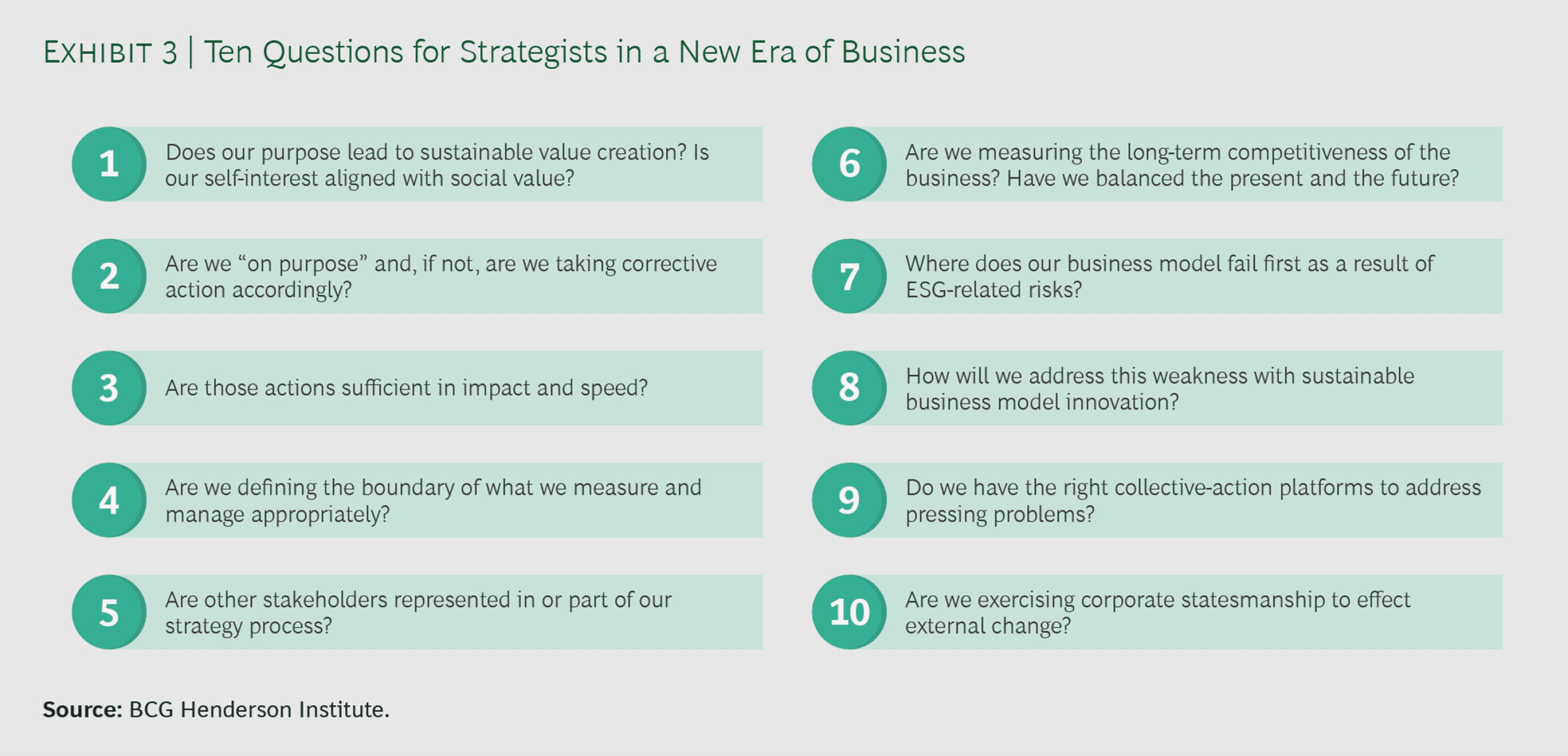

This new type of strategy will flip thinking from “company-out”, to “societal needs-in”, by asking how a specific SDG target could be met by extending the company’s capabilities, assets, products, services, and ecosystem … and those of its industry. Exhibit 2 lists 10 questions that strategists should incorporate into their strategy processes to ensure that they embrace the opportunity to create shareholder returns and societal impact.

However, these new strategies cannot be simply grafted onto existing business models. Business models themselves will need to be transformed. Sustainable business model innovation (S-BMI) will take a much wider perspective than traditional business model innovation. It will take account of a broader set of stakeholders; the system dynamics of the larger socio-environmental context; longer time horizons for sustaining adaptable advantage; the limits of business model scale, viability, and resilience; the entire cradle-to-grave production and consumption cycle; and the points of leverage for profitable and sustainable transformation.

2. Transform business models.

We can already observe seven topologies for sustainable business model innovation, sometimes in combination, all with the potential to increase both financial returns and societal benefits.

“Own the origins” — compete on capturing and differentiating the societal content of inputs to production processes, products, or services. For example, capture those inputs produced with cleaner energy, sustainable practices, preserved biodiversity, recycled content, inclusive and empowering work practices, minimized waste, digitized traceability, fair trade, etc. Performance here will require differentially advancing the societal performance of the supplier base and its stewardship of resources, communities, and trade flows. Achieving this may require backward integration to assure fast and complete upstream transformation and then holding and using these new capabilities for competitive advantage and differentiation.

“Own the whole cycle” — compete by creating societal impact through the whole product usage cycle from creation through end-of-life. This competitive typology puts a wide aperture on the business and requires systems analysis to uncover business models that offer the richest competitive and financial options. For example, design for circularity, recyclability, and waste-to-value; create offerings that enable sharing rather than owning to assure high utilization of resources and end-of-life value; construct enabling infrastructure to facilitate circularity and repurposing; integrate into other value chains to capture societal content; educate and enable consumers to choose whole-cycle propositions on the basis of value to people and planet. Expect to reposition operations, reinvent supply chains and distribution, pursue new backward or forward integration, acquire business adjacencies, or undertake unconventional strategic partnering to achieve these ends.

“Expand societal content” — compete by expanding the societal content of products or services on six dimensions of benefit: economic gains, environmental sustainability, customer life well-being, ethical content, societal enablement, and access and inclusion. Then advocate new standards, escalate transparency and traceability, tune marketing and segmentation, engage customers on the product’s wider value and their involvement in bigger change, and seek premium pricing. In business-to-business offerings, help customers integrate the full societal value of your products, services, and business model into their own differentiation and ESG ambitions.

“Expand the chains” — compete by extending the company’s value chain, layering onto other industries’ value chains to extend the reach of your products and services and the societal impact for both parties, while changing the economics and risks of doing so. For example, use the reach of a consumer products distribution systems to carry payments and financial services to small merchants; layer one company’s health services onto another company’s physical supply chain to benefit its workers and their families while expanding markets for health services; or connect byproducts from one company’s operations as feedstocks into other companies’ value chains.

“Energize the brand” — compete by digitally encoding, promoting and monetizing the full accumulated societal value that is embedded in products and services, along the full value chain from origins to customer, from cradle to grave. Use such data to rethink differentiation, the brand experience, customer engagement, pricing for value, ESG reporting, investor engagement, and even launching new businesses. For example, strengthen the brand with promotions that showcase the business’ performance on the open, clean, green, renewable, and inclusive attributes of its operations; and build higher customer engagement and loyalty by using data on the product’s environmental and societal footprint to empower customers in choosing on how their lifestyle affects the planet and its people.

“Re-localize/Regionalize” — compete by contracting and reconnecting global value chains to bring societal benefits closer to home markets in ways stakeholders value. For example, build local and regional brands that better express local tastes and values; source from smaller local producers to minimize logistics emissions and strengthen local economies; reimagine production networks against total environmental and societal costs; capture local waste streams as new feedstocks into preprocessing; or reconstitute jobs for micro-work to use local talent.

“Build cross-sector” — compete by creating new models that include the public and social sectors to improve the company’s business and societal proposition, particularly in emerging and rapidly developing economies. For example, work alongside government bilateral aid institutions and NGO development organizations to improve the agricultural capacity of small farmers so they become reliable sources of agricultural inputs to the agro-processing value chain; partner with global environmental organizations and governments to promote the reuse of ocean plastics as feedstocks to production systems; partner with governments to strengthen and corruption-proof social safety nets through digitization and electronic payments; or partner across sectors to restructure recycling systems to enable higher penetration of waste-to-value business models. Extend this into industry coalitions for collective action that reshapes broader rights-to-operate and generate new opportunities.

All seven types of S-BMI create new sources of differentiation, operating advantage, network dynamics, and societal value — enabling more durable and resilient businesses benefiting shareholders and wider society. But to assess and improve the performance of these business models and communicate their value, we need to expand today’s scorecards.

3. Change scorekeeping and transparency.

Mangers will need new scorecards for a fuller equation of business value to assess and reward performance and inform decision making. While today’s ESG measures are a start, their mindset and use, as for most non-financial reporting, remains anchored in compliance, not business advantage. Consequently, scorecards and reporting must go beyond mapping general ESG materiality. Instead, they should focus the business and its stakeholders on insightful metrics that directly connect the company’s unique purpose and business models to the way the company creates differentiated value and societal impacts — its full business value (FBV).

These metrics will assess performance throughout the value chain — from procuring inputs, to owning the post-use cycle, and the company’s full societal footprint. As with financial performance, good companies will integrate these metrics into their managerial software — operating plans, target-setting, investment decisions, executive compensation, and employee recognition. Further, the company will promote radical transparency of its FBV scorecards fully reflecting them in investor relations and corporate communications, quarterly calls, and annual meetings, and making them integral to marketing, social media, public relations, and government affairs. As such, stakeholders will see the company in new ways and its advantages relative to peers on new dimensions.

4. Lead a purpose-filled organization.

Talent prizes purpose. Consequently, winning and engaging the best talent in the ’20s depends on reinforcing a motivating purpose that captures the bigger ambition of the business beyond profit and gives employees meaning in their work. Research shows that companies with a motivating purpose have higher employee engagement, and that higher engagement correlates to better financial performance. So purpose is a win for recruiting employees with “mission-mindedness” and enhancing the organization’s energy and performance.

But building a stronger organization with the right capabilities will take rethinking the skills and capabilities that can really differentiate company performance on both financial and societal metrics. The organization can no longer delegate sustainability and social responsibility to individual departments; rather, those mindsets need to be fully integrated into operations and decision making. That requires augmenting line businesses with nontraditional business skills — finding people capable in systems thinking, anthropology, social dynamics, behavioral economics, sustainability, and development policy.

Those workers will become part of agile teams that conceive innovative operating models optimizing for both operational effectiveness and societal benefit within value chains, markets, and customer segments. That requires developing and rewarding new ways of working that are more flexible, embedding rapid cycles of learning and deployment, and reaching into the wider business and societal ecosystem to create positive change and performance. Successes in doing so create the stories that bring purpose alive for the organization and energize its culture.

5. Build corporate statesmanship.

It will take the scale and capacity of entire industries and their ecosystems to help solve society’s biggest challenges, such as reducing plastic or food system wastes. Thus, farsighted leaders will turn threats to their industry’s right-to-operate into opportunities to reinvent and expand their industry. Rather than ignoring these risks or mobilizing their government affairs groups to block change, they will instead practice strategic statesmanship and build coalitions for collective action within their industry, and sometimes across industries, to find and scale new solutions.

As in their own companies, they will articulate a compelling purpose and vision for how the industry and ecosystem could expand the total value delivered to society, while also assuring the industry’s longevity, profitability, and resilience. As corporate public goods, they will promote platforms that foster pre-competitive R&D, scale solutions, expand access and inclusion, accelerate industry learning and standards, and build capacity in the larger industry ecosystem. They will seek new partnerships with the public and social sectors that could multiply what the industry could accomplish alone and shape new models of collective action for positive societal change.

6. Elevate board governance.

Boards need to build new capacity to responsibly guide management toward setting an ambition for the full role the corporation will play in society during the ’20s. As with current management, most directors spent their careers focused on financial performance, with some sidelined activities in CSR and sustainability. However, to steer the company in this new era of business and hold the CEO accountable for the company’s financial, environmental, and societal performance, boards will need to be educated on the societal needs and SDGs; they will need directors with different skills and life experience in the social sectors; and they will need to restructure committees, charters, and policies to provide oversight on social performance. They will need to challenge long-held views about the boundaries and time horizons of business, about what makes a good CEO, about new risks and rights-to-operate, and about measuring performance, and they will need to expand their view of managerial competence beyond the ability to hit annual business targets. And they will assess whether management is building a more resilient and adaptable company delivering for shareholders and society even at the cost of optimizing today’s business model.

It is an exciting era for leaders, business and society. The above agenda challenges us to re-conceive business, commit to purpose, and pursue sustainable business model innovation. Doing so will open up new opportunities for growth, shareholder value, and benefits to society and the planet. CEOs and their boards can wait to be pushed into this agenda by competitors, customers and regulators. Or they can embrace it proactively, and use it to reinvent the company, reshape the industry, propel the stock, deliver remarkable impact, and leave a notable legacy of corporate public good.