This is the first in a series of articles about the future of technology in Europe and the lessons from China to build its economic sovereignty.

For decades, the European economy has been characterized by industry and, even today, its importance cannot be overstated. According to the European Commission (EC), industry accounts for 80% of Europe’s exports and private innovations, and in sectors such as automotive, building materials, and luxury goods, European players are global leaders. However, times are changing, and the current COVID-19 crisis is a dire reminder that the level of digitization of firms coincides with both their resilience to such unexpected events and their competitiveness in a new business reality centered on Digital. For instance, this crisis highlights how advanced robotics can enable companies to continue operating autonomous factories in spite of containment measures, how machine learning and data analytics allow us to detect early signs of changes in customer preferences, and how AI-augmented supply chain management increases a firm’s agility in responding to fast and drastic changes in supply and demand.

Assessing the level of Europe’s digitization should start at the source, with the tech industry, in which Europe is clearly lagging behind. All Tech Giants are based in the US and China, and they also have acquired the most promising European startups (e.g., Skype, Deepmind) over the last years, leaving Europe with very few “unicorns” today (only 11% of the worldwide total). Furthermore, the tech industry can no longer be regarded in isolation. It is telling that in only five years’ time, Alibaba managed to create the world’s largest money market fund.[1]It was the largest at some point in 2019, after which it shrank due to regulatory pressures aiming to decrease systemic risks. HBS professors and acclaimed authors Marco Iansiti and Karim R. Lakhani are accurate when they say, “We cannot escape the fact that digital and analog worlds are becoming one. We are not looking at the ‘new economy,’ we are looking at the economy.” So, as Europe’s industrial players need to make the move to digital, how can they avoid following the same unsuccessful trajectory as its Tech industry?

Especially in light of the grave economic consequences of COVID-19, the time for Europe to act is now. In previous crises, the key to thriving in the post-crisis world has been to make transformational moves, taking into account long-term goals. Digitizing will be this type of move for European industry players. If they fail to make this digital transformation, they will wake up in a new reality, where the logic of competitive advantage will inevitably be different.

Industry in Europe lacks digital applications

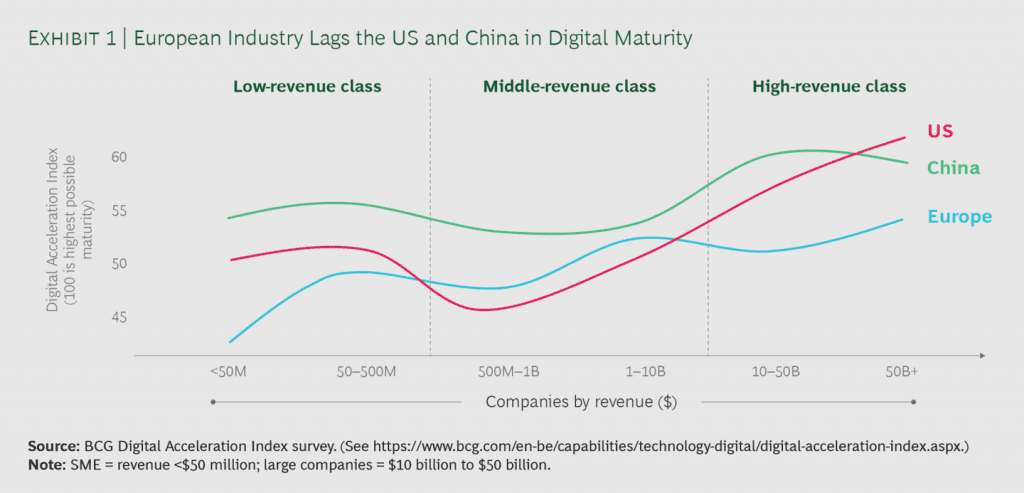

BCG research sheds light on companies’ digital maturity across regions.[2]This research asks companies to self-evaluate their digital maturity, along a variety of dimensions (business strategy, core operations and functions, digital business growth, ability to leverage … Continue reading Exhibit 1 is clear — and worrying for Europe. In the low and high-revenue classes, the difference in digital maturity is vast. And while Europe performs better in the middle-revenue class, it still trails China. These findings resonate with the European Investment Bank’s analysis that digital adoption in EU companies is growing but largely trails that of their US counterparts, across sectors. With Europe’s reliance on vertical industry players, missing this wave of digitization is not an option. The EC rightfully stresses that “the slow uptake of digital technologies poses a risk to the European Union’s ability to compete in the global economy.”

The question is what causes this disparity? It is not that European small and midsize entities (SMEs) are different in nature. When surveying thousands of SMEs across China, the US, and Europe, we find that they all face very similar issues hampering further digitization: a lack of financial resources, technical capabilities, and talent. So if the difference is not in initial SME capabilities, what then is behind this disparity in digital maturity?

Two elements drive China’s strong performance

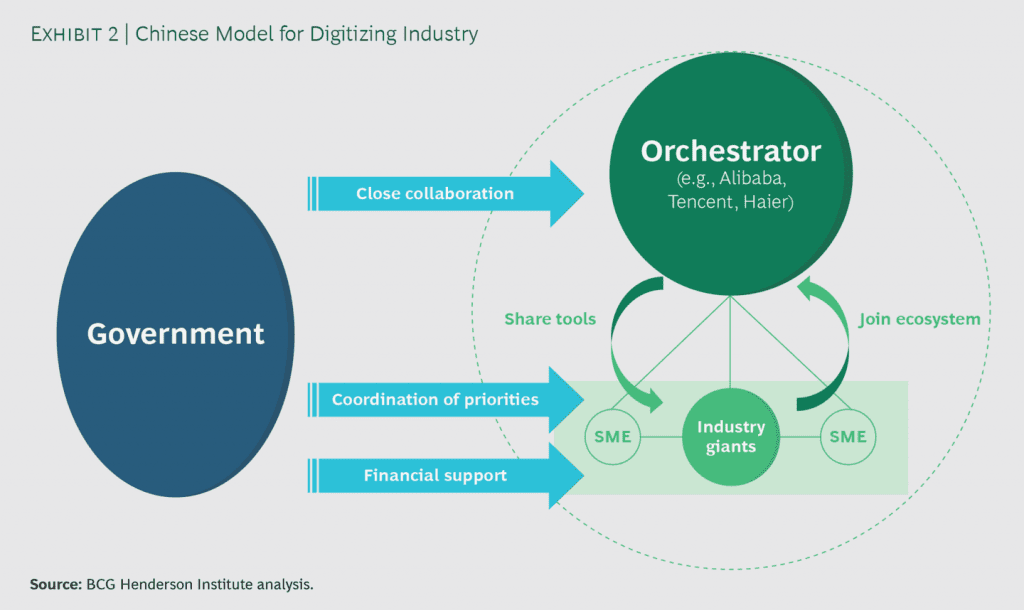

In the US, a Schumpeterian “creative destruction” process — companies that are losing their competitive edge are swiftly replaced by more productive ones — operates relentlessly. Laggards either upgrade their digital capabilities or risk being disrupted. Although this Schumpeterian process has also played a role in China, comparatively more focus has been placed on transforming traditional industry players. Europe needs exactly this type of change, with its current strong industrial position and lack of technology scale-ups. To plan for this type of transformation, a full understanding of what drives China’s success is helpful (Exhibit 2).

As so often in China, governments play a critical enabling role. The central government is responsible for coordination. It sets the overall ambition, distributes funds, and ensures coordination. The difficult choices it makes are crucial to this coordination. To avoid wasteful duplication, it gives support only when an industry has a comparative competitive advantage in a certain location. To the contrary, if there is no comparative advantage, the location’s focus needs to shift to other economic activities. In this way, the central government ensures an adequate amount of competitive industrial ecosystems arises across the country.

Nevertheless, provincial and regional governments do play the most active role. They independently plan and implement digitization strategies. They follow three key principles:

- Plans are grounded in the central-government ambition, in line with its priorities.

- The governments cooperate closely with digital orchestrators.

- SMEs are heavily supported with grants and financing.

This approach has tremendous impact. For example, the Guangzhou provincial government works with Alibaba on a large-scale, smart-manufacturing plan, which aims to bring 20,000 companies to the cloud by mid-2021.

The strongest digitization pull on industry players comes from Chinese digital orchestrators such as Alibaba, Tencent, and Haier. Here we define digital orchestrators broadly, including purely digital players but increasingly also hybrid ecosystem orchestrators. Many examples of platform orchestrators digitizing SMEs have made headlines over the past few years. The most high-profile ones are Alibaba and JD.com, which are digitalizing the fragmented Chinese retail industry. By offering digital infrastructures to shop owners for free, these digital giants managed to digitize over one-third of China’s 6 million stores in less than 2 years. In return, shop owners agreed to share data, reinforcing the digital ecosystems and serving as fulfillment and delivery centers. Haier is another great example with its COSMOPlat platform, which integrates more than 4 million SMEs to foster mass customization in manufacturing.

But this pull is not limited to SMEs — it has impacted industrial giants in meaningful ways as well. Indeed, as most of their up- and downstream partners turn digital with the help of orchestrators, these larger companies are indirectly forced to follow suit. Failing to do so may eventually result in ecosystem exclusion.

Through its strong focus on government coordination and digital orchestrators, China develops a win-win-win:

- Chinese industrial players digitize faster.

- Central and local governments sustain local employment.

- Digital giants reinforce their ecosystem.

Europe falls painfully short where China excels

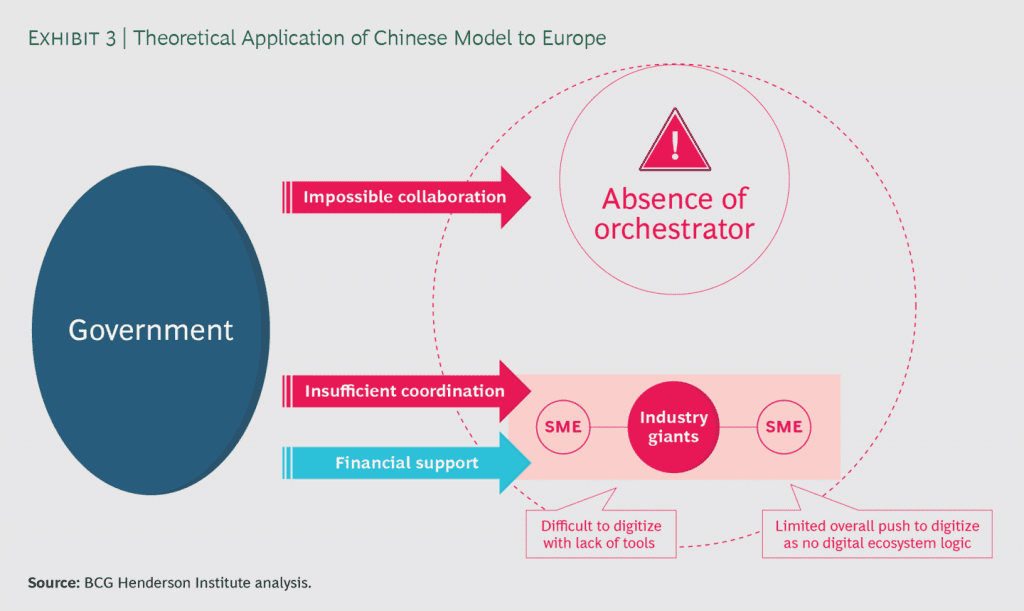

There is no such “win-win-win” in Europe (Exhibit 3), as Europe fails on the dimensions that enable the Chinese model. First, European government action is too fragmented. Europe is aware of the critical need to digitize its industry. “A Europe fit for the digital age” is one of the key priorities of the new EC, and the EU’s budget appropriation to drive the digital agenda for 2021–2027 is 1.6 times higher than before.

Nevertheless, the lack of central coordination, planning, and prioritization hinders the actual impact of any actions taken. Indeed, as Marc Andreesen notes, Europe doesn’t need 50 Silicon Valleys. It needs distinct variations, each focusing on its comparative advantage. The EC’s Digital Innovation Hub (DIH) initiative is revealing. The organization spent €500M to support the set-up of DIHs, which help SMEs to test digital technologies and train the companies in the use of these new technologies. Now, the EU is home to 450 digital hubs, more than twice the number in China. This regional focus (“one hub per region per industry”) has spread resources too thin, resulting in subscale efforts and duplication.

Second, European digital ecosystem orchestrators do not exist, which has negative consequences. One issue is that European SMEs experience less of a natural pull to digitize. Therefore, they are required to act independently in a bottom-up manner, resulting in slower increases in digital maturity. In addition, European industry players end up overseas when looking for partnerships. This puts them at a disadvantage, as they have to operate according to foreign standards and regulations.

Europe urgently needs to address these two problems if it hopes to maintain the competitiveness of its industry. How can it do so?

Action from both public and private sectors is required for Europe to succeed

First, European governments should immediately start creating the conditions for European homegrown platform companies to emerge, rise, and thrive. To do so, the EC should:

- Build a true “Digital Single Market” that goes beyond fundamentals such as infrastructure. A good example is the Common European Data Spaces proposed in the European data strategy, but more such efforts are needed and implementation will be key.

- Drive regulation to foster European digital sovereignty. A digital single market can be a fertile breeding ground for platform companies only if it presents a level playing field. When foreign platform players operate in Europe, they should do so on European terms, following European rules and values.

- Support an adequate number of digital ecosystems per industry on a European level. Countries need to stop fragmented pilot projects in each country. Two or three leading digital ecosystems per industry in Europe is the highest level of fragmentation it can afford. As in the Chinese example, difficult choices need to be made based on comparative advantage.

- Align on roles between the EU and local governments. The Chinese model where the central government decides priorities, allocates funds, and coordinates can serve as an inspiration. If this type of model is not followed, duplication and red tape may even make the situation worse.

Still, as Volkswagen CEO Herbert Diess pragmatically points out, today “we don’t have the big tech companies here and you need tech companies to partner with. Therefore, either we can go to the US West Coast or we can go to China.” Until such European Digital Giants emerge, Europe needs a concrete workaround to “catch the train” of Digital in Industry and keep it from falling further behind. A preferred option would be the “Europeanization” of foreign digital players, ensuring immediate impact whilst reducing over-reliance on foreign technology. To stay in the lead in their relationship with foreign Digital Giants, companies and governments should jointly:

- Ensure European IP and co-creation. Working closely together with foreign partners on R&D is key to achieving the appropriate knowledge transfer.

- Protect European digital jobs once created. Since 2011, US digital titans have acquired more than 60 leading-edge European technology companies like Skype and Deepmind. This problem will continue as long as no pan-European VC or Nasdaq-like stock exchange is established.

- Push for “made in Europe for Europe.” While the origin of foreign digital players will remain non-European, localizing (part of) the value chain should be incentivized. Many players have made commitments (e.g., Microsoft and the Brussels region have partnered to sustain the development of the IT sector in the Brussels area), but more needs to be done.

This challenge is not just one for Europe’s industry players. To continue thriving in Europe, digital ecosystem orchestrators need to rethink the way they operate. Committing to European value creation needs to become a principle guiding strategic choices, rather than a compliance effort.

Furthermore, independent from government action, European industrial players urgently need to become fully digital-ready. To reach that stage, they should:

- Merge digital and vertical capabilities and disrupt their own sector. Ping An, a traditional insurance player in China, presents a good example: it joined forces with Tencent and Alibaba to initiate China’s first pure digital insurance company.

- Be ready for ecosystem cooperation, beyond traditional partnerships. BMW and Daimler’s archrival partnership is a step forward, yet is still conservative. Further sharing of data to integrate a larger dealer or supplier network in one ecosystem could be the next step.

During the 19th century, China was the biggest economic power with one-third of global GDP. But it missed the second industrial revolution and became a colony. Let’s not allow Europe to follow the same path in the 21st century by missing the digital revolution and becoming a digital colony of the US and China. Europe has great assets, but only if united: it is the leading region in terms of the absolute number of AI talent, and at least one-third of the 40 top universities in AI research are European. We believe that, to address Europe’s digitization trap, policy makers and companies have a joint and coordinated role to play. And there is an urgency to act. Europe can succeed, only if it can embrace the change. As Lampedusa wrote: “If we want nothing to change, we need everything to change!”