The looming demographic crisis faced by developed countries is borne out by alarming statistics. By 2050, all 38 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) will have aging populations; in all but 5 of those countries, 21% or more of the population will be aged 65 or older.

This trend carries critical implications, including possible labor shortages, declines in productivity and innovation, and shrinking domestic demand, among others. But aging populations—in effect, populations in decline—do not just create headwinds for GDP growth. They also have a profound impact on citizens’ overall well-being, a metric we assess through factors such as mental and physical health, human connections, and job engagement. At the same time, economic growth and well-being are linked—with both negative feedback loops and synergies between the two. The good news is that this interplay creates opportunity—the countries that best understand the dynamics have the greatest chance to forge a winning path forward.

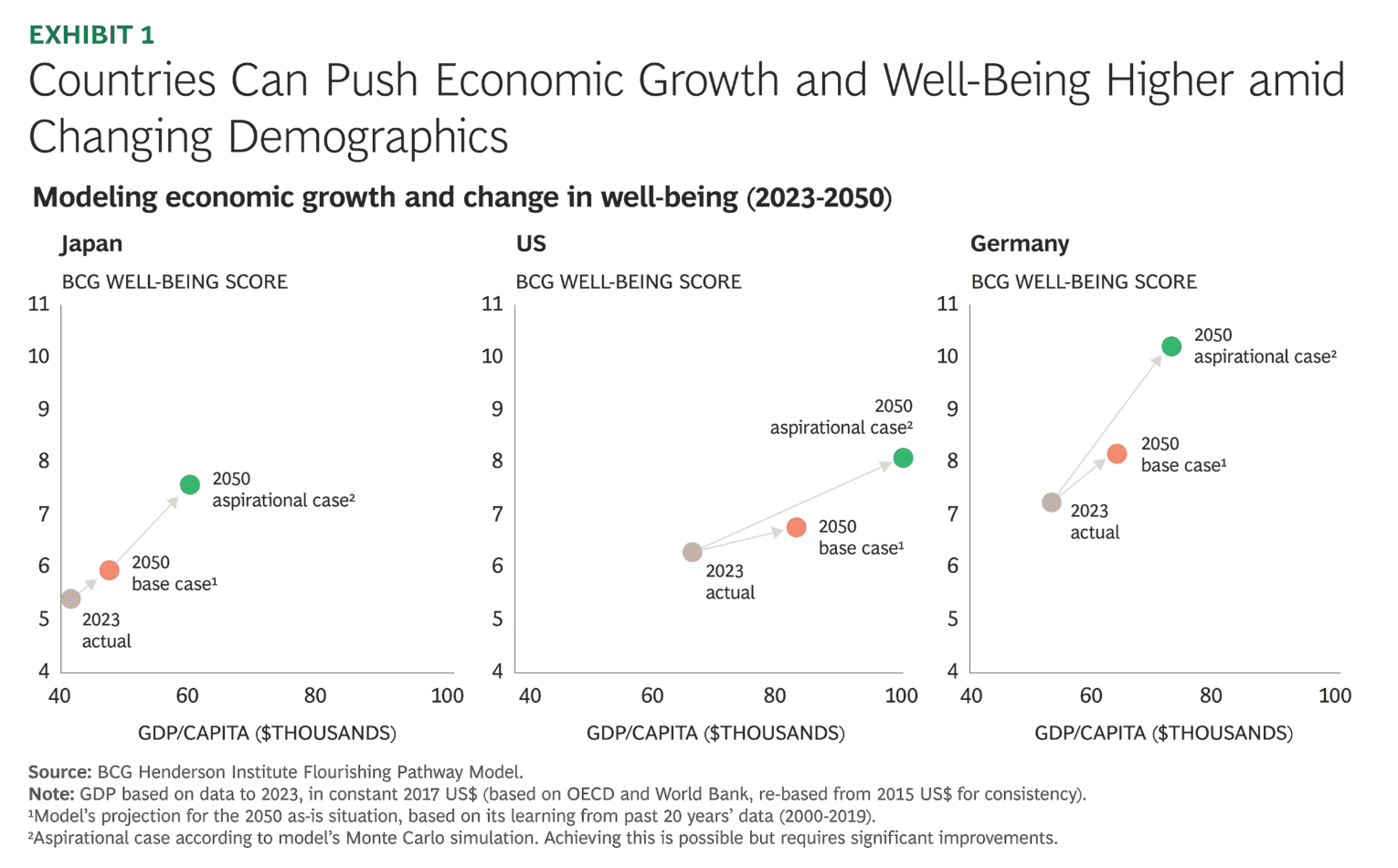

To understand both the challenges and opportunities ahead, the BCG Henderson Institute (BHI) developed a proprietary neural network model. The model, which draws on 40 indicators for 13 OECD countries for the past 20 years, can project an individual country’s economic performance and its citizens’ well-being through 2050 under thousands of different scenarios.i Leveraging the model, we can assess how economic growth and well-being would evolve through 2050 under both a business-as-usual approach (our base case) and one in which actions are taken to optimize for both factors (the aspirational case). A look at both scenarios for Japan, the US, and Germany points to ways countries can potentially drive meaningful improvement in the pathway ahead. (See Exhibit 1.)

A deep examination of Japan, which has been grappling with an aging population for decades––longer than most other OECD countries—yields further insight. The Japanese government has developed a broad-based strategy to address its demographic challenge, actions likely to move it closer to the aspirational case in the coming years. But our work found that Japan and countries like it can do even more to enhance their trajectory.

Our model is not intended to be crystal ball or to direct government policy. Rather, it identifies the levers that could play a role in shifting a country’s trajectory. Most important, our work reveals that demography is not destiny. Countries can build a future in which both their economies and citizens thrive. Moreover, our research reveals a vital role for the private sector; corporate action not only can help ensure that companies have the engaged, productive workforce they need in the future, but it also can contribute to building a more vital, prosperous society.