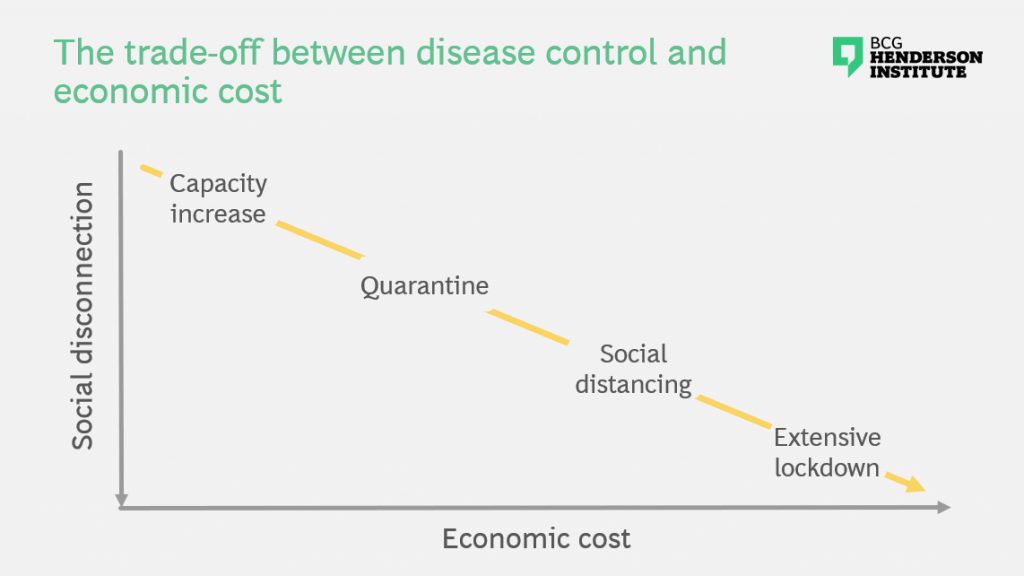

Controlling COVID-19 has proven to be very hard. We now know that one of the few effective measures we have to reduce the spread of the infection is strict social distancing, applied early. Unfortunately, social distancing applied monolithically creates a second serious problem: it prevents the flow of people and goods and puts the economy into a coma, potentially damaging livelihoods for millions.

Furthermore, this dilemma is likely to be with us for some time, since most estimates suggest we are unlikely to develop a vaccine and deploy it at scale in less than 18 months; and recent studies indicate that, while the disease has infected many more people than official statistics show, it’s nowhere close to a level that might confer population immunity. We are therefore entering a protracted period of uncertainty where we have to deal with the trade-off of economics and health.

Our current policy toolkit offers no ethical or politically viable way of balancing lives and livelihoods. Premature release of restrictions on interaction could easily reignite exponential growth of infections, as has happened already in Hong Kong and Singapore. Indefinite lock-downs, on the other hand, could cause unprecedented economic damage. Furthermore, even if we could in theory make such a tradeoff, we currently have no way of calibrating and managing it, as it is beyond the reach of our experience and our models.

We therefore need to innovate to break the tradeoff. This requires new integrated strategies that address both the health and economic dimensions of the challenge. And it should include not only technical solutions to breaking the tradeoff, but also the imperatives for coordinated collective action, which address the known hurdles and constraints we face today. This is necessary because the political, economic, and social dimensions of the problem are critical and highly interconnected, and because deficiencies in any geography could easily undermine overall effectiveness. In other words, to solve the biggest dilemma of our time, we need a holistic approach.

General strategies for disease control

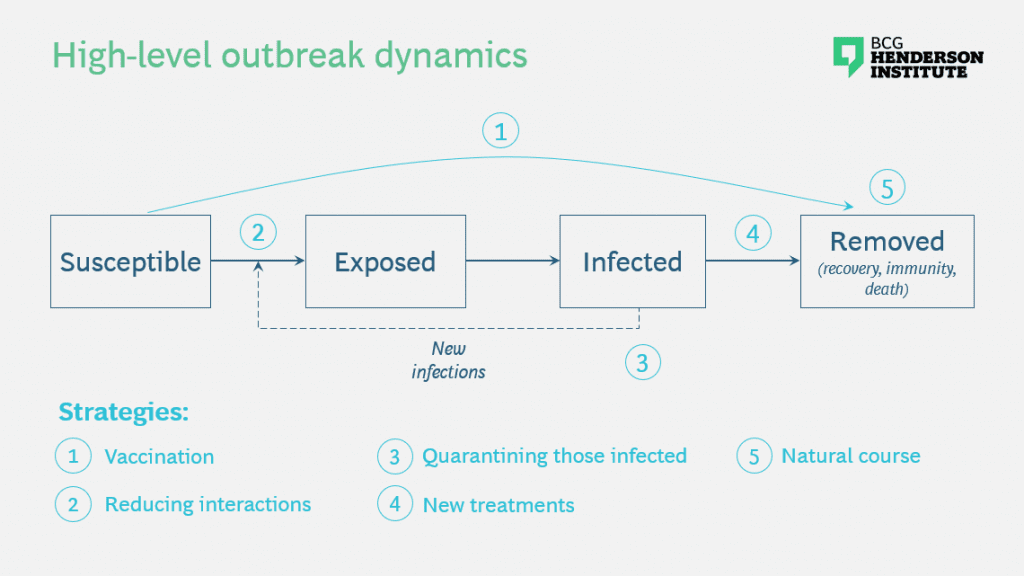

Epidemiologists model diseases by looking at the dynamics of different subpopulations of individuals, distinguished by their health status, demographic features and other characteristics. In the simplest case, we can distinguish between those who are Susceptible, those who are Exposed, those who are Infected (whether they are symptomatic or asymptomatic) and those who are Removed from the susceptible population by acquired immunity (recovery or vaccination) or death.

The simplest strategies to apply at the level of the population are 1) vaccinating people so they are no longer susceptible; 2) reducing the likelihood of exposure by limiting physical interaction and improving hygiene practices; 3) quarantining infected individuals to reduce their interactions with the susceptible population; 4) developing new treatments to increase recovery rates of those who are infected; and 5) allowing the disease to take its course thereby accelerating the acquisition of population immunity.

Unfortunately the first measure may be at least 18 months away from becoming feasible; the third is hard once community infection has set in, especially because many infections are asymptomatic;[1]See for example “Universal Screening for SARS-CoV-2 in Women Admitted for Delivery” (New England Journal of Medicine, April 2020) https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2009316 the fourth will likely require several months of drug trials and scaling up production if a successful candidate is found; and the fifth is untenable because of the very high human costs given current penetration and mortality rates. Societies have thus far chosen the second strategy of widespread social distancing as being the most feasible. It has proven effective when applied early; but it has already created unprecedented economic damage, as we can see from record unemployment rates, rising bankruptcies, and declining stock prices and GDP forecasts.

Therefore, companies and societies can’t continue to rely on this strategy indefinitely while merely waiting for an “all-clear” to return to business as usual. Instead, we need to design new strategies that will allow some activity to resume while also effectively addressing the health risks that remain while the virus is active.

Possible strategies to break the trade-off

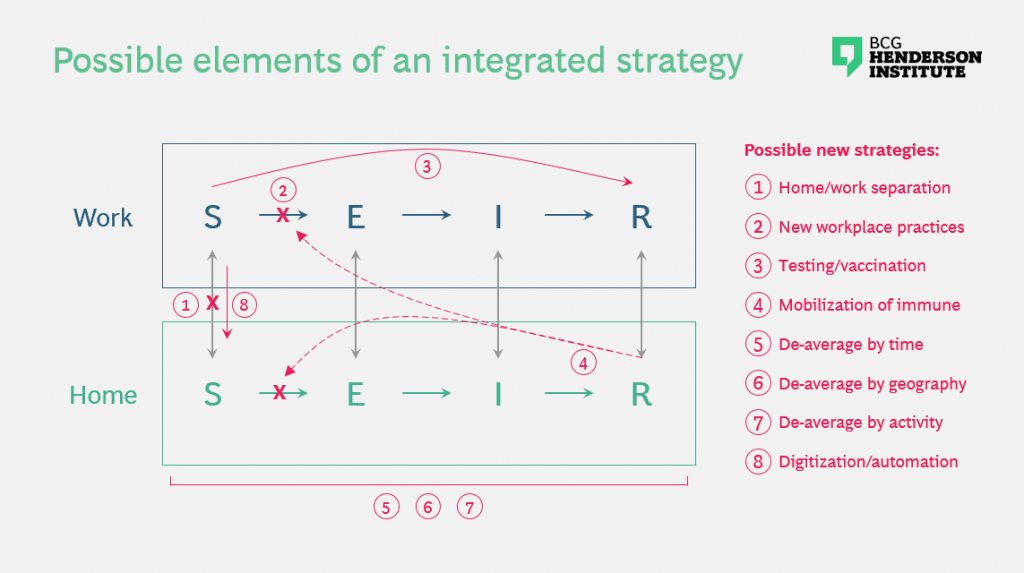

To generate new strategies that address the dilemma between disease control and economic viability, we need to bring the interplay between home and the workplace into the picture. Simplifying slightly, we can think about the dynamics and interactions of S, E, I and R populations in both arenas and frame potential strategies that allow the human interactions necessary for economic activity which do not undermine disease control.

In the spirit of seeding new ideas, we present a few possibilities that could fulfill this aim. None are easy, or tried and proven, but unprecedented problems require new solutions.

- Balanced separation of home and work. Shelter-in-place has generally implied sheltering at home, precluding any work that involves physical proximity. However, a few companies, like the Italian energy company SNAM, have set up dormitories and support structures to maintain key corporate facilitates, thereby preserving social distancing while enabling essential activities like the distribution of energy and necessary goods.

- New workplace practices that minimize infections. One characteristic of resilient systems is modularity — firebreaks that prevent problems in one part of a system from bringing the system down. Some companies have already begun to create non-overlapping teams to run essential facilities at different times. Combined with sanitization between shifts, strict hygiene and interaction protocols, and greater selectivity of who is admitted to critical facilities, this can reduce the odds of exposure at work by ensuring that an infection in one team does not spread to the other team.

- Testing and eventually vaccination in the workplace. If economics is the science of scarcity, we will surely be faced with a situation in the coming months where the most important scarce goods become personal security and health status information. To the extent that testing and later vaccination capacities are limited, it makes sense that we apply those scarce resources where they can have the greatest benefit — such as healthcare workers and those charged with bootstrapping the economy.

- Selective mobilization of the immune. With sufficient testing, we can identify Recovered individuals and release them back into the workplace, provided they are immune and no longer infectious. A more powerful variant of this strategy is to direct these individuals into roles that involve physically interacting with Susceptible or Infected individuals, such as in healthcare, deliveries, and personal services. Not only does this allow more interpersonal interaction to occur, enabling more economic activity than does strict isolation, but it also enhances disease control by creating an “immunity shield” between infected and susceptible individuals.[2]Weitz, “Intervention Serology and Interaction Substitution” (April 2020) https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.01.20049767v1

- Deaveraging across time. The premature release of social distancing controls could have disastrous consequences, but if downward trends in diagnoses, hospitalizations, and deaths continue, we will eventually arrive at a point when the relaxation of controls makes sense. However, there will be a non-negligible risk of recurrence, especially given our incomplete understanding of the epidemiology. With the right metrics and sufficient agility, we could release controls while maintaining the ability to reimpose them rapidly enough to contain the disease if necessary.

- Deaveraging across geographies. Nationwide social-distancing policies have the merit of consistency but the demerit of very high economic cost. The trajectories of different cities and countries will likely continue to be very different. By de-averaging geographically, measures can be applied where they are needed and relaxed in other places. This would similarly require again extensive testing to understand outbreaks in progress and the agility to reapply measures as needed. It would also require some well coordinated constraints on travel between certain regions.

- Deaveraging across activities. As we reach the point at which relaxing controls makes sense, not all activity will be able to restart at once. We will therefore need to deliberately allocate labor and resources to activities that are most essential to rebooting the economy, while continuing to limit activities that have a substantially elevated risk of re-accelerating the outbreak (for example, events with thousands of spectators).

- Accelerating digitization and automation. Much knowledge work can be done from home, and the current extended period of social distancing is accelerating the adoption of digital products, services, platforms and remote working. While some activities will always inherently require physical interaction, more digital adoption in other areas will reduce the risks associated with returning to work. Given plausible scenarios of up to a 2 year period of ambiguity before the disease is controlled, it seems feasible that accelerated digitization and business model innovation for minimal contact could be catalyzed with sufficient effort.

Requirements for collective solutions

Many of the above strategies are not feasible within our current constraints. Given the stakes, however, it makes sense to revisit what we consider to be feasible. When faced with an existential threat, societies have sometimes been able to achieve seemingly impossible goals in short periods of time — for example, the rapid reconfiguration of US industrial production in the run-up to World War II, or the international agreement to protect the ozone layer by phasing out production of chlorofluorocarbons. Today, potential areas for rapid mobilization include a massive acceleration of viral and antibody testing, and the development and rollout of anti-viral treatments and vaccines — which would each dramatically increase the range of available strategies for restarting economic activity.

In other words, breaking the trade-off between health and economic outcomes requires not just new technical strategies, but also collective action and mobilization against common challenges. This presents a number of additional challenges, many of which are common to other tough collective problems, like climate change. Successfully overcoming them will necessitate meeting several key requirements:

- Knowledge. Many promising potential strategies require applying measures selectively to certain segments of the population. But without knowing which individuals are susceptible, infected, or immune, we have little choice but to be monolithic in our policies. In particular, large-scale viral and antibody testing are essential to progress. While the barriers to acceleration — investment, regulation, logistics, materials, and coordination — might seem insurmountable under normal circumstances, we need to question them given what is at stake and set aspirations that might seem unreasonable. If we can put a man on the moon, or eliminate smallpox, why could we not accelerate testing 10- or 100-fold?

- Learning. There are many unknowns with respect to the characteristics of the virus, the effectiveness of different strategies, and how social and economic systems will behave in response to different interventions. As scientific research continues to accelerate and countries reach different stages at different times, we will certainly be exposed to many opportunities to learn. However, whether we do learn collectively, effectively and rapidly is not guaranteed. To date, it appears that we have not been able to fully apply what has been learned from science and from other countries’ experience to our collective benefit. We therefore need to strengthen our learning mechanisms by looking widely for signals, filtering solutions in an agile manner, and amplifying what we know. To do so we need to create knowledge structures and a source of truth or credibility.

- Education. This in turn sets up the need to educate policymakers and the general public on the lessons learned and required behaviors. Without the backing of policymakers and the cooperation of the general public, any sufficiently complex strategy that needs to be applied broadly is bound to fail.

- Coordination and consistency. A small amount of leakage between different cities, states, or countries could easily undermine the effectiveness of any strategy, and the cost of failure is high. Coordination between various governments, employers, and societies is essential, particularly if de-averaging measures are to be applied. The margin for error is reduced with any strategy that involves finer distinctions in time or space. At the highest level, a global problem requires a global solution, rather than fragmented solution elements applied differentially in different places.

- Governance. Coordination and consistency in turn require governance. We don’t really have global governance that is strong enough for the tough global problems we face, including COVID-19. Indeed, the institutions that we have are currently subject to criticisms, and there is a rising current of blame allocation and nationalism that could defeat our efforts to solve our challenges. It may seem unrealistic to assume that we can do anything about this in the short term, but unreasonable times require unreasonable measures. The pivotal variable here is leadership. Who will lead us to a common solution, and will we demand and create such leadership?

- Compliance. The enemy — the virus — has the potent weapon of exponential growth, which means that a tiny leakage from control measures, such as infected people traveling undetected between geographies, can undermine any policy and spell disaster. We therefore need the knowledge and authority both to create and to enforce compliance. South Korea and China have shown that technology can help achieve this. Privacy norms vary across nations, of course, but new solutions may be able to avoid an either/or choice between privacy and health outcomes. We may however be forced to recalibrate the balance between privacy and health, if we want to defeat the disease.

- Agility. Generally speaking, the larger the organization, the less nimble. But coming back to the virus’ weapon of exponential growth, a week of indecision can quadruple the size of the problem. We need to cut through bureaucracy and make sure that we are able to act promptly within and across governments and companies.

- Resource allocation. We likely can’t have testing and vaccines everywhere we need them in one fell swoop. We will therefore need to prioritize where we apply measures and resources first, requiring strong leadership and education.

- Incentives. We need to create incentives for those who bear the brunt of the cost or risk, to encourage them do so in our common interest. Otherwise deep social divisions could open up which undermine progress.

To avoid immense health or human costs, we will need to go beyond the essential first steps of mitigating the outbreak and develop new strategies that can allow us to resume some economic activity. However, technical solutions will do minimal good if we are not able to apply them effectively and consistently. Therefore, the problem needs to be looked at holistically, across geographies and constituencies and overcoming hurdles to collective action. And leaders from science, business, and government need to urgently come together to develop such common strategies and platforms for cooperation.