Companies are increasingly embracing sustainable business model innovation (SBM-I) to simultaneously address environmental and societal challenges and create competitive advantage. But those efforts often run into significant constraints stemming from the underlying structure, resource and capability bottlenecks, and other limitations of the broad socio-economic ecosystem in which companies operate.

Overcoming these constraints to develop scaled, sustainable solutions often requires coordination, collaboration, and co-designing of solutions by multiple actors in the ecosystem, including suppliers, customers, employees and governments. For example, when Unilever first committed to use only cage-free eggs for their Hellmann’s Mayonnaise in North America by 2020, there simply were not enough cage-free hens in the US to meet their demand. As a sustainability pioneer, they had to rebuild their supply chain working with independent third-party verifiers to improve supplier practices, ultimately achieving their commitment three years ahead of schedule. Today, we see companies like Tesla actively reshaping their ecosystem to ensure greater sustainability and competitive advantage.

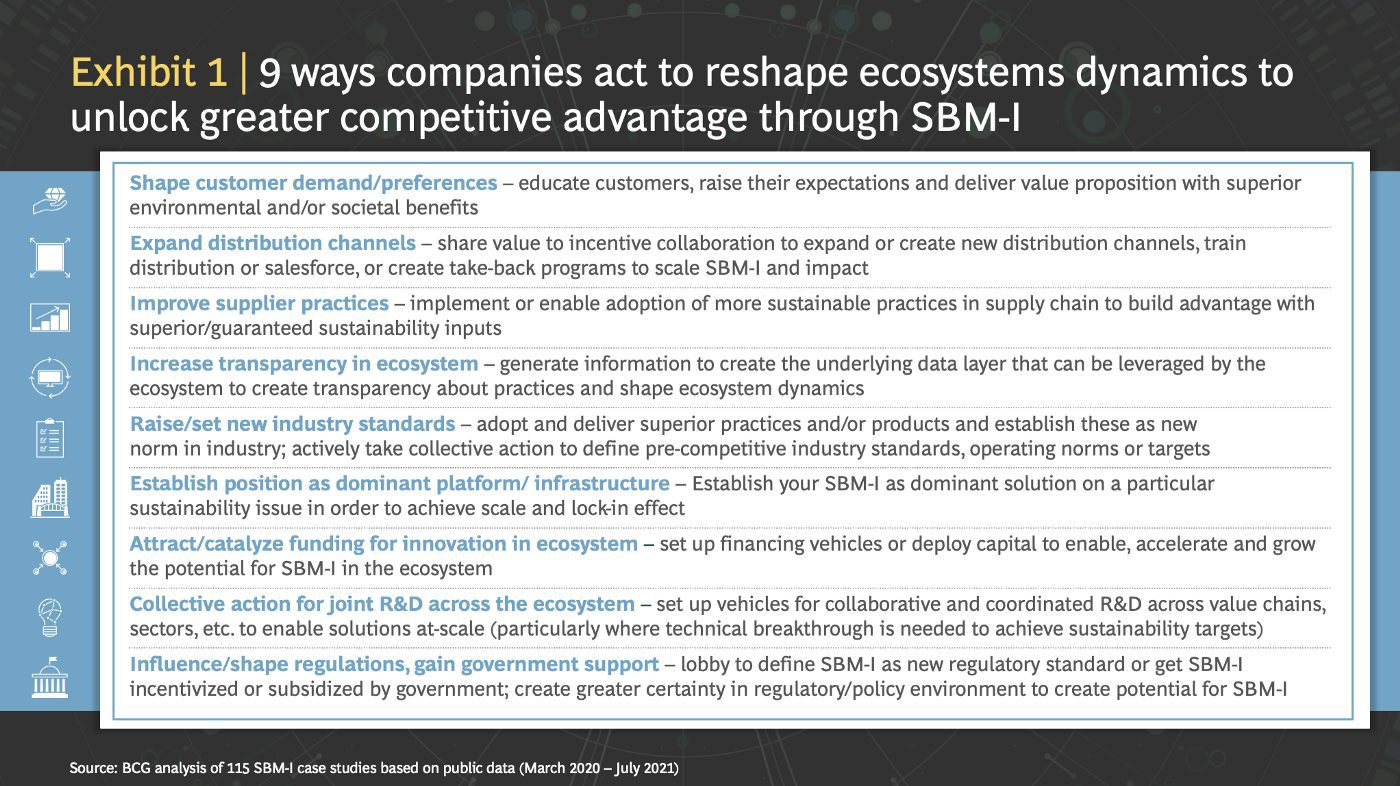

But how can companies reshape the dynamics of their socio-economic ecosystem? As we’ve previously outlined, companies should start by systematically mapping their ecosystems to determine where there are meaningful constraints to SBM-I. Our research of 110+ in-depth case studies identified nine ways in which companies can then remake their ecosystems to unlock those sustainability constraints. (See exhibit 1)

Some companies, it turns out, are already putting these approaches into action. Over 90% of SBM-Is we studied are reshaping the dynamics of their ecosystem in at least one way. Meanwhile, sustainability front-runners use combinations of 4 or more of these modes to alter ecosystem dynamics. In particular, front-runners are far more likely to seek to establish themselves as the dominant platform or infrastructure than other SBM-Is.

The nine modes we observed were:

1. Shape customer demand and preferences. Companies can educate customers and raise their expectations to demand products and services that generate superior environmental/societal (E/S) benefits. For example, Docomony, founded in Sweden in 2018, has created the “DO” mobile banking platform to track and offset consumers’ CO2 emissions, and also offers its “DO Black” credit card which limits spending when a carbon threshold is reached. With these two products, Doconomy educates and incentivizes customers to significantly change their spending habits and demands, for example by buying from more sustainable merchants.

2. Expand distribution channels. Companies can expand or create new channels to distribute products or recycle products at their end-of-life by sharing value to incentivize collaboration. This can include training new salesforces to distribute products in rural environments or creating take-back programs to scale recycling programs. Interface, the world’s largest manufacturer of modular flooring, is now offering the world’s first ‘carbon negative’ flooring products which are made from recycled contents and bio-based materials and store carbon — preventing its release into the atmosphere. The company has expanded its supply of recycled materials, including by working with coastal communities to collect and recycle fishing nets into yarn and establishing programs to recycle vinyl-back carpet tiles.

3. Improve supplier practices. Companies can work with suppliers further up the supply chain to adopt more sustainable practices. For many SBM-Is this creates advantage through guaranteeing a supply of more sustainable inputs. For example, Primark partners with the NGO CottonCollect to train women smallholder farmers in India to adopt sustainable farming practices that boost yields while reducing the use of chemical pesticides, fertilizer, and water intensity. This effort has helped the company expand their supply of sustainable, organic cotton used in its “Primary Cares” line.

4. Increase ecosystem transparency. Trust within an ecosystem is critical to creating the right incentives and verifying the inputs used in sustainable products. Companies can generate data and analytics that create transparency about sustainable production practices (for example child-free labor); environmental and societal impact (for example the. carbon content of inputs); and certifiable origins of sustainable products (for example sustainable fisheries). In Singapore, Sembcorp developed a blockchain Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) platform that aggregates RECs and allows companies to purchase them to offset their carbon footprint. The platform boosts transparency, integrity, and competitiveness in the renewable energy market.

5. Raise or set new industry standards. Companies can adopt more sustainable practices and/or deliver more sustainable products — and then advocate and catalyze alignment around these solutions to establish them as new norms in the industry. This also includes working collaboratively to set new industry standards among players across the value chain. Finnish oil and gas company Neste, for example, has become a leading player in renewable fuels and chemicals and currently Chairs the Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB). In that position, the company has participated in the establishment of RSB’s globally recognized industry standards and certifications for sustainable biofuels.

6. Establish position as dominant platform or infrastructure. Companies that can make their platform or infrastructure the primary means for solving a specific sustainability issue can enable sustainable solutions to achieve scale while locking in their competitive advantage. Consider, TEESS a 50–50 joint venture of Total and Envision. TEESS combines Total’s robust experience in energy production and commercial operations with Envision’s AIoT Operating System (EnOS), the world’s largest IoT energy platform, to develop on-site, distributed generation, solar projects for B2B customers in China.

7. Attract or catalyze funding for ecosystem innovation. Companies can set up joint-financing vehicles and/or mobilize and deploy capital to enable, accelerate and grow sustainability innovations within the ecosystem. For example, BNP Paribas has pioneered Sustainability-Linked Loans (SLLs), which allow companies to lower their cost of funding based on the achievement of certain sustainability targets and KPI’s.

8. Collective action for joint R&D across the ecosystem. Companies can establish vehicles for collaborative and coordinated research and development of scalable solutions, efforts requiring alignment across many players within the ecosystem. Often this R&D focuses on fundamental components of underlying industry infrastructure that must be re-invented to enable greater sustainability for all parts of the value chain. Collaborators contribute financial resources, complementary capabilities, and expertise talent. For example, established in 2020, the Maersk Mc-Kinney Moller Centre for Zero Carbon Shipping to conduct joint R&D on priority areas that are needed to decarbonize the maritime industry.

9. Influence or shape regulations, gain government support. Companies can work with regulators and policymakers to establish new regulatory standards or make policy changes to directly subsidize, incentivize and de-risk sustainable business models and sustainable innovation. For example, in the run-up to COP26 many corporate-led sustainability alliances have begun to call for clear government policy on carbon pricing. Recently, the CEO Climate Dialogue, a corporate sustainability alliance that includes oil and gas super majors, utilities, and chemicals companies called for significantly reduced emissions and for market-based policy approaches that assign a cost to greenhouse gas emissions.

In order to maximize the advantage found in sustainability, companies must quickly establish where and how they need to reshape their ecosystem for advantage. Depending on the constraints at issue, they can then adopt one or more of the nine modes outlined above to alter ecosystem dynamics. The best approach to executing each mode may differ. For example, companies that want to reshape an ecosystem by changing supplier practices may decide to build partnerships on their own with NGOs or may decide to take collective action through a sustainability alliance, working with their competitors to influence supplier practices. In other instances, for example, companies aiming to attract funding for ecosystem innovation, it may be necessary to build an entirely new “business ecosystem” — a specific form of collective action wherein a dynamic group of independent businesses create products or services that together constitute a coherent solution to a marketplace or consumer need.

There is no doubt that driving ecosystem-level change is a complex undertaking. But companies that understand how their broad ecosystem needs to evolve — and know the right means to drive that change — will emerge as winners in the race for SBM-I.