This research was published on July 16, 2020

In normal times, the public debt does not feature much in conversations with investors and business leaders, who tend to view it as a detail of the macroeconomic context. But coronavirus has made the macro context critical to companies’ outlook, and public debt — which has jumped near record levels in many economies including the U.S. — attracts much concern. This is understandable, since sovereign debt problems could create a more toxic business environment than even a deep recession. Has debt risen too far too fast, and should we worry about it?

While public debt is discussed widely in the current context, it is also widely misunderstood. It’s tempting to think that more is worse, that higher levels go with greater risks, that a recession must make debt less sustainable, and that there must be a critical level of debt that marks a breaking point.

In reality public debt is far more complex and debt levels are a poor indicator of economic risk. Paradoxically, the Covid-19 crisis will likely strengthen the debt capacity of certain economies, particularly the U.S., and the biggest risk near-term is too little, rather than too much debt.

To see how Covid-19 drives sometimes surprising public debt dynamics globally and locally, we must consider the interplay of growth rates and interest rates, the influences on the relationship of these two variables, particularly during and after moments of crisis, and what the balance of risk will likely be between too little and too much debt — particularly if there is risk of politicizing deficits and debt levels during the upcoming U.S. election.

WHY DEBT LEVELS ARE A RED HERRING

While habitual use of public debt to generate artificially higher growth is ultimately problematic, it’s worth remembering that more debt is better than less debt in times of crisis, such as this one. When the real economy is in freefall, rising debt levels can contain the collapse of firm and household balance sheets and foster recovery. In fact, the failure to use fiscal policy helped push the U.S. economy into depression in the 1930s , and swift and strong policy responses by central banks and governments have so far prevented even worse (systemic) meltdowns today.

Yet, despite such necessary spikes, debt levels (the debt-to-GDP ratio — total public debt divided by total national income) are watched carefully and widely warned against now. There is often talk of “thresholds”, i.e. levels that will trigger debt crises or a slump in growth. Yet, while the desire for a simple metric is understandable, public debt does not work as mechanically as this.

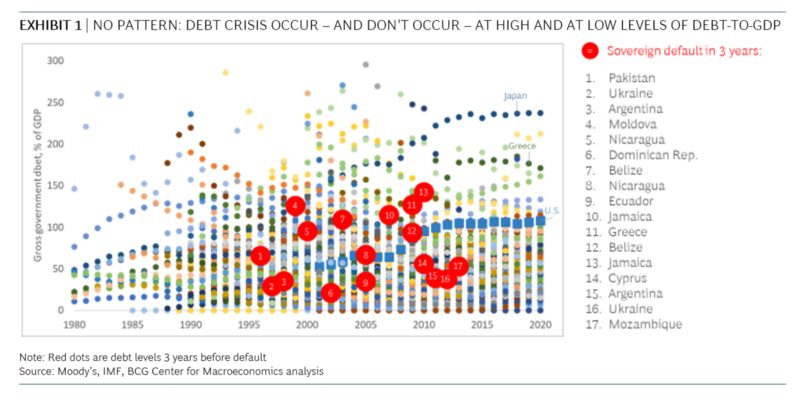

Consider the public debt levels for 190 countries over 40 years along with recorded sovereign defaults (Exhibit 1). There is no correlation between debt levels and defaults. Instead, the data tell us, quite clearly, that sovereign debt crises occur — or do not occur — at high levels and at low levels of debt.

INSTEAD OF DEBT LEVELS, FOCUS ON “R-MINUS-G”

The difference between an economy’s nominal interest rate and nominal growth rate offers a much stronger framing of risk.

As long as nominal interest rates are below nominal growth (i.e. r-g<0) there is no additional burden in keeping debt-to-GDP levels stable. Put simply, all interest can be paid by issuing new debt and the debt ratio would still fall. Alternatively, the debt ratio can be kept stable even while adding new debt unrelated to interest (to the tune of the difference of r and g times the debt ratio). And if the debt ratio can be held stable with little effort, there are fewer reasons to be worried about sustainability and crisis.

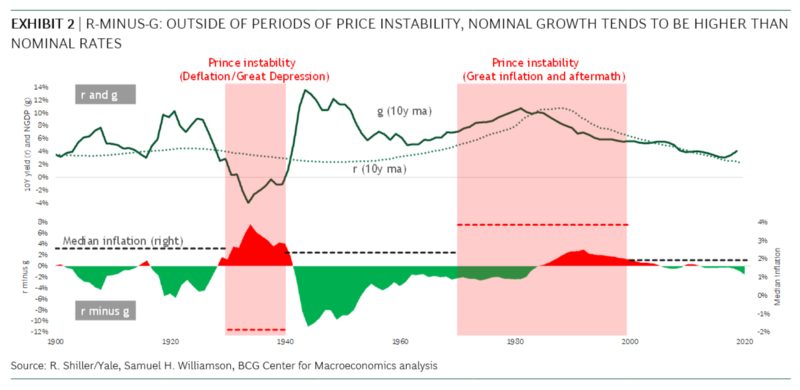

Is r-minus-g < 0 a normal or an exceptional state of affairs? The U.S. economy over the last 120 years tells us that nominal growth exceeding nominal rates is the norm. In fact, r>g is the anomaly, which has occurred only around periods of price instability (specifically, deflation in the 1930s or in the aftermath of too high inflation — the 1980s and 90s). In fact, this favorable backdrop (r<g) is common in many parts of the world.

It’s worth noting that r-minus-g can be favorable (i.e. the spread is negative) for different reasons: either because growth is very strong or because rates are very low. While it is intuitively preferable to have a negative r-minus-g spread because of very strong growth, one resulting from very low rates has the same mechanical impact on debt dynamics.

TO ASSESS COVID-19 IMPACT, LOOK AT DRIVERS OF “R-MINUS-G”

To assess how Covid-19 impacts a country’s sovereign debt capacity and risks, we must take two analytical steps: first, understand the drivers of r-minus-g, and second, analyze if Covid-19 can impact those drivers and thus an economy’s r-minus-g dynamics. A handful of drivers shape r-minus-g:

1. Inflation regime

Low inflation and inflation expectations deliver low nominal interest rates. When they are low and stable, inflation risk premiums (as opposed to just inflation compensation) will be low on public debt, helping rates stay low relative to growth (favorable r-minus-g spread). Thus, the inflation regime is crucial to delivering a favorable r-minus-g regime.

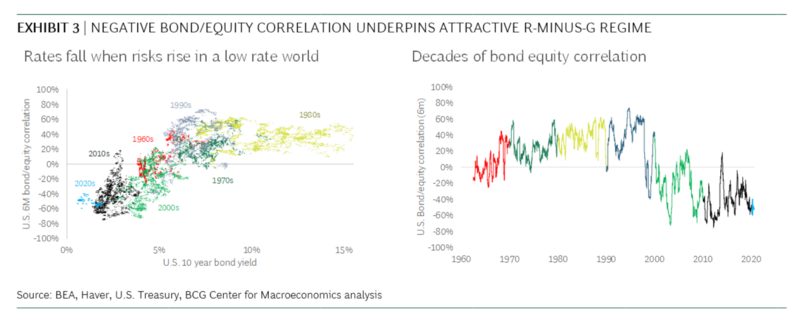

2. The correlation of risk and interest rates (bond/equity correlation)

Negative risk/rate correlation describes economies where interest rates fall (bond prices rise) during periods of crisis, such as the current one. In other words, because the public debt of some economies provides valuable insurance against falling risk assets (such as equities), demand for such debt is higher. The price for this insurance comes in the form of lower rates received by investors on that public debt, helping drive a favorable r-minus-g spread.

3. Global demand for currency

Rates can also be pushed down by demand that is driven by reasons other than return. Reserve holders, i.e. those countries holding a specific currency, such as the U.S. dollar, to provide themselves with a backstop in a crisis, are a key example. The more debt (currency) that is held by reserves holders, the lower the rate is likely to be and thus a more favorable r-minus-g spread. So, the question is whether there is reserve currency status, how strong it is, and whether a crisis can change it.

4. Supply side drivers (trend growth)

We must not forget g in r-minus-g. If growth falls below rates, as it surely does in times of contraction such as the current recession, that seems like a problem. However, what matters is not the short run but the longer term, i.e. whether rates will fall further and for longer than growth or not. But changing long-run growth is hard. Nominal growth (g) is the sum of trend growth and realized inflation. And trend growth doesn’t typically change over short periods of time or because of shocks. Rather, it is a function of slowly-changing drivers (labor input, capital input, and productivity growth), suggesting even a severe shock will have a hard time pulling down trend growth.

PARADOXICALLY, COVID-19 STRENGTHENS SOME COUNTRIES’ DEBT CAPACITY

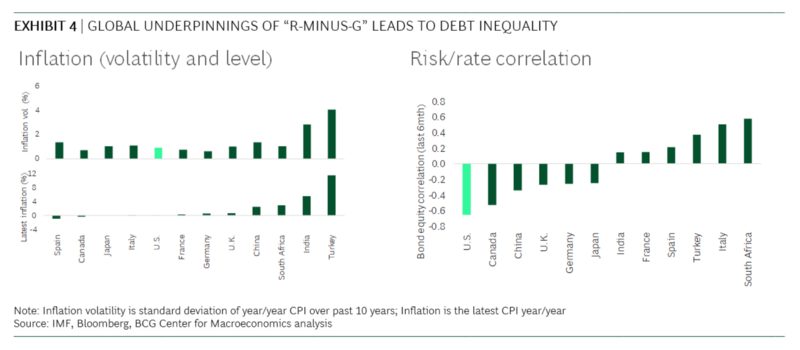

If we consider the drivers above, it becomes apparent that Covid-19 will likely spawn significant debt inequality in nations’ capacity to sustain debt — even as debt levels are going up everywhere.

Paradoxically, some economies’ debt capacity will likely rise with Covid-19 — irrespective of their debt levels — as rates will be suppressed for longer than growth (contributing factors are fears of deflation, higher demand for the insurance provided by negatively correlated assets, increased demand for reserves after a crisis, and policy rates staying low). For other economies, it will be the opposite, potentially pushing their economies into debt defaults, currency crisis, and inflation. Largely speaking, it’s the wealthiest economies that benefit, underlining the inequality of the crisis.

To illustrate, consider the U.S. case, though this describes numerous other economies too. There is much concern about U.S. debt levels (81% of GDP, and 108% if we include debt that the government holds itself). While such numbers are high relative to most of the country’s history, the narrow focus on debt levels is blind to the fact that r-minus-g is quite favorable for the U.S. and Covid-19 likely makes it even more favorable in the medium run.

If we consider the drivers of r-minus-g outlined above we can see why:

- In the U.S., the inflation regime has a strong foundation with deeply anchored expectations. The risk of a structural inflation break is very low. If anything, fears tilt towards deflation, plausibly putting a negative inflation risk premium on interest rates;

- Risk/rate correlation is deeply negative, and indeed the insurance value of public debt (rates) has been exhibited in the current crisis when equities crashed, and U.S. debt rallied (yields fell from 1.92% at the start of the year to 0.54% in early March);

- The value of holding U.S. dollar reserves in the rest of the world was proven again as the crisis pushed the dollar higher, and it’s worth noting that there is no viable competitor for the primary reserve currency;

- Lastly, trend growth (i.e. growth outside of cyclical fluctuations) is unlikely to be affected by Covid-19. The crisis will deliver a one-off hit to capital formation as businesses fold, capex falls, and the capital stock grows by less. However, permanently changing the supply side drivers (labor, capital, and productivity) is a high bar, even for a severe crisis.

COVID’S IMPACT FURTHERS DEBT INEQUALITY GLOBALLY

Yet, there are many weaker economies with unfavorable r-minus-g dynamics or whose favorable dynamics could flip to unfavorable (the crisis flipping r to be greater than g). It is important not to equate unfavorable r-minus-g dynamics with “emerging economies”. There are advanced economies with unfavorable r-minus-g (e.g. Italy), and there are emerging economies with very favorable r-minus-g (e.g. China).

The truly unfavorable and risky situations are those economies where rates exceed growth by a large margin — South Africa comes to mind. In many such economies the drivers outlined above work in opposite directions: unstable inflation, positive risk-rate correlation, and, contrary to reserve currency status, such countries must build reserves and worry about outflows. Also, while r-minus-g captures debt risks far better than just debt-to-GDP levels, the framework faces its own limitations as national idiosyncrasies can play a large role. For example, reliance on foreign currency debt, such as Turkey’s, adds dimensions of vulnerabilities not captured by domestic currency r-minus-g.

THE RISK NEAR-TERM IS NOT “TOO MUCH”, BUT “TOO LITTLE”

As economies begin to reopen and the risk of extended first waves, second waves, and new lockdowns persist, debt will continue to play an important role in containing the damage and shaping the recovery. In other words, the balance of risk is in favor of too much rather than too little, certainly in those economies whose debt capacity is likely to grow as argued above. In assessing the role of debt in the months ahead, the key analytical risks are:

- Underestimating the importance of debt growth to recovery and the risk of politicization in an election season — the bipartisan efforts in March could falter and turn further debt growth (i.e. stimulus) into a political football.

- Mistaking debt-to-GDP levels as a measure of debt sustainability, when in fact it is a poor indicator of risk. Assessing nominal interest rates and growth rates and the forces influencing their spread is a stronger lens on debt risk.

- Inferring country risk from economic development levels: there are advanced economies with weak debt capacity and emerging economies with strong debt capacity.

We continue to believe that the COVID crisis will not translate into a regime break (See: HBR — The U.S. is Not Headed Toward a New Great Depression) as policy makers and politicians ultimately have strong incentives to avoid that devastating outcome. But as the crisis passes and the critical need for stimulus lessens, the balance of risks will shift away from “too little” and towards “too much”.

At first this will come from the falling benefits of stimulus but when the economy re-gains a strong footing new risks may emerge. This will be particularly true if aggressive stimulus remains in place and pushes on the inflation regime of low, stable, and well-anchored inflation expectations. While cracking the healthy inflation regime would take time (years) and is a high bar (repeated policy errors), it is not implausible in an age of “compulsive stimulus” and any crack in price stability would severely undermine debt capacity. At that point the balance of risks would be the opposite from what they are today and the economic consequences severe. While today it remains clear that more debt (stimulus) is safer than less, that does not mean debt growth can continue into perpetuity.