Around the globe, average lifespans are increasing—a clear advancement for humanity—and fertility rates are falling, which is also a positive development, to the extent that it reflects greater freedom of choice on childbearing. However, taken together, these trends are creating an aging global population that is expected to result in significant economic and societal challenges, driven by a declining labor force, increased health expenditures, and higher pressure on social safety nets.

The impacts of societal aging are already unfolding: This year, China experienced its first population decline in more than 6 decades, and Japan, where nearly 30% of the population is already 65 or older, is experiencing labor shortages, increased financial uncertainty among older people, and a contraction of the domestic consumer market. These effects have been particularly acute in rural areas throughout Japan, where it is now common to see empty houses or shops and abandoned farmland.

While the causes and impacts of this demographic challenge have been widely discussed, there is a dearth of solutions that could ensure a flourishing aging society and economy. To make progress on this front, we assembled a group of thought leaders from academia, healthcare, the public sector, the arts, and the corporate world in our 2023 Meeting of Minds.

The participants included:

- Aisha Dasgupta, Demographer

- Partha Dasgupta, Frank Ramsey Professor Emeritus of Economics, University of Cambridge

- Nicholas Eberstadt, Henry Wendt Chair in Political Economy, American Enterprise Institute

- Sam Karita, Managing Director and Senior Partner at BCG and leader of the BCG Henderson Institute Japan

- Simon Levin, James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University

- Wolfgang Lutz, Founding Director of the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital and Professor of Demography at University of Vienna

- Nicole Maestas, Margaret T. Morris Professor of Health Care Policy, Harvard University

- Hiroaki Miyata, Professor at Keio University’s School of Medicine

- Yumiko Murakami, General Partner of MPower Partners, former head of the OECD Tokyo Centre, and former MD at Goldman Sachs

- Martin Reeves, Managing Director and Senior Partner at BCG and Chairman of the BCG Henderson Institute

- Haruka Shibata, Professor at the Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies at Kyoto University

- Gary Shteyngart, New York Times bestselling author of Super Sad True Love Story, Absurdistan, Little Failure, and The Russian Debutante’s Handbook

- Feng Wang, Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Irvine

Below, we summarize key insights from the meeting, which include a more nuanced understanding of the challenges, a view on the elements of potential solutions, and the implications for businesses and their leaders. (For those interested in further reading, we are sharing the provocations written by each participant, related to their unique area of expertise.)

A nuanced understanding of the challenges of demographic aging

Globally, increasing lifespans and falling fertility rates are creating aging populations. Over the past century, average lifespans have increased significantly around the globe. For example, in the U.S., average life expectancy at birth rose from 46 to 76 years between 1900 and 2021. Key factors underlying this development are improved healthcare (such as the availability of antibiotics and vaccines), hygiene and sanitation, and food safety practices such as dairy pasteurization and water chlorination.

In parallel, fertility rates have been declining sharply: In the U.S., childbirths per woman have more than halved since 1960, from around 3.6 to 1.7 today. This is driven, among other factors, by the increased availability of contraceptives, higher labor force participation by women, lower infant mortality, and changing social and cultural norms, including choosing to have fewer children to offer improved opportunities to each (for example, education).

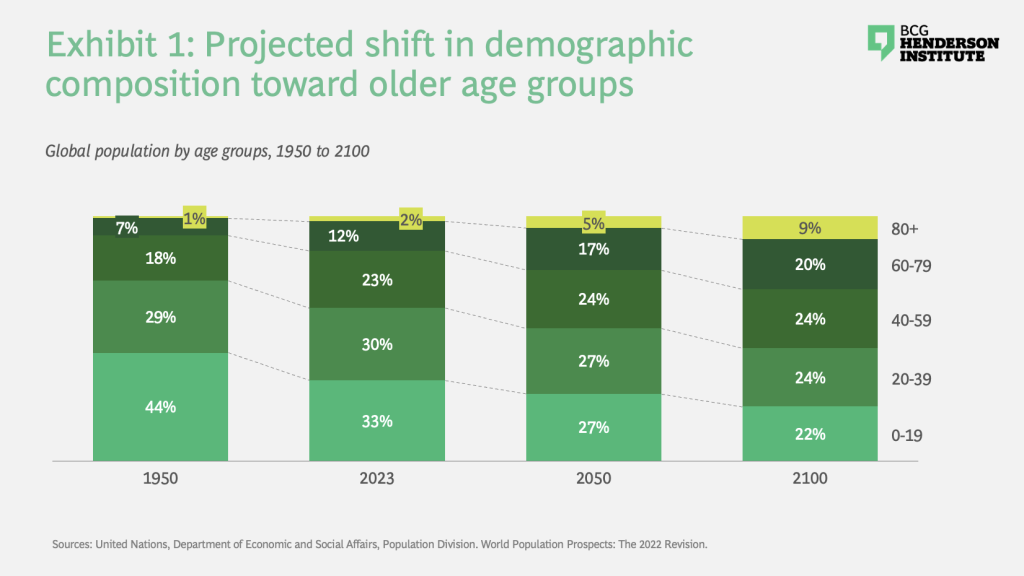

Together, these trends are creating an aging population: The global median age has increased from 22.2 in 1950 to 30.5 years today. While people aged 19 and younger are still the largest age bracket (compared to those 20–39, 40–59, and 60+), their share of the global population has fallen dramatically since 1950 (from 44% to 33%). By 2100, the largest of the above brackets will be those aged 60 or older (see exhibit 1).

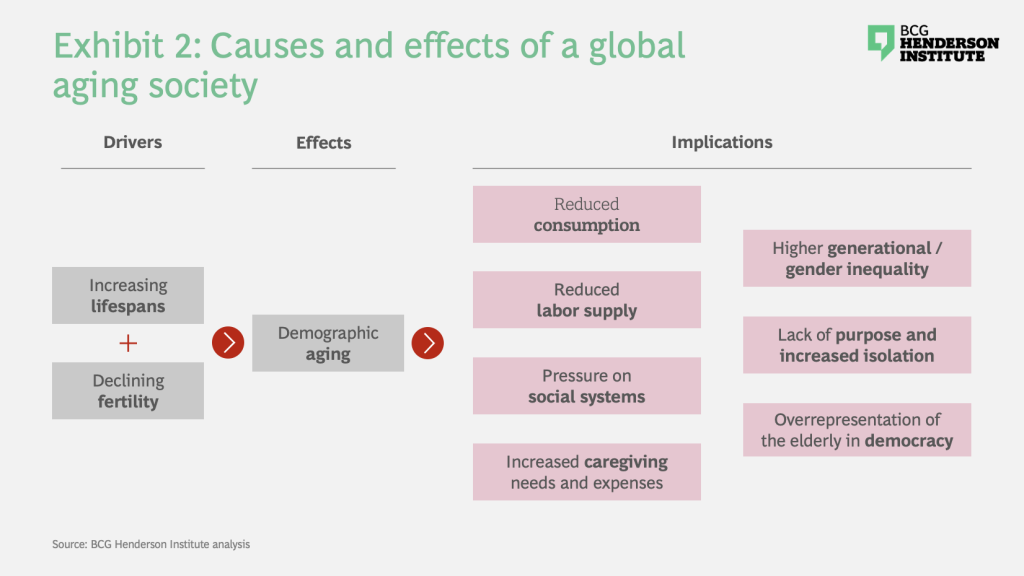

Our society’s demographic transition will create significant challenges (see exhibit 2, below, for a simple summary):

- Lower labor supply: Aging populations will cause decreases in labor supply (under current patterns of age-specific labor force participation) in many regions: Across OECD countries, the population aged 15–64 is projected to shrink by more than 92 million people by 2050 (for reference, the total OECD population stands at ~1.3 billion).

- Declining economic growth: Some researchers fear that, together with a diminishing workforce, a shrinking consumption base may significantly reduce economic growth: One study suggests that in the period from 2005 to 2050, the OECD countries could experience a 25% drop in economic growth from changes in population age structure alone.

- Pressure on social safety nets: Programs such as pension systems will be stretched, due to a rising number of pensioners and a longer duration of retirement. Within the EU, one study is projecting the old-age-dependency ratio (the ratio of people above 65 to those aged 15 to 64) to rise from 0.31 in 2019 to 0.57 by 2100.

- Pressure on healthcare and caregiving systems: More care will be required to treat higher rates of disability, dementia, and other illnesses associated with old age—both in terms of acute and long-term institutional care as well as home-based care from family or friends.

- Potential for increased gender and generational inequality: The burdens of caregiving fall disproportionately on women, often pulling them out of the workforce at critical career stages, which may exacerbate the gender pay gap. Aging may also create or highlight imbalances in wealth and prospects between generations.

- Overrepresentation of elderly in democracies: An increased proportion of the elderly in society, combined with the higher rate with which older people vote in democratic systems, may result in an overrepresentation of the elderly in democracies, possibly biasing policies toward their interests.

- Increased loneliness, social isolation, and feelings of purposelessness: Aging societies may experience an “epidemic of loneliness” due to an increasing proportion of people who become socially isolated after the loss of loved ones or retirement. Older people may also find it more difficult to find meaning in life, potentially contributing to an additional “epidemic of purposelessness.”

While the preceding conventional description of the causes and impacts of demographic aging is broadly accepted, our meeting highlighted several nuances that contribute to a deeper understanding of the challenge.

Measuring and forecasting the challenges of aging is itself a challenge. In general, future policies, global disruptions, and trends around fertility (or anything dependent on human agency) are hard to predict, raising concerns regarding the reliability of demographic forecasts. Specifically, any projections of the dependency ratio based purely on chronological age—such as the study for the EU referenced above—are incomplete. When layering in factors such as labor force participation, education level, and expected migration patterns, projections suggest that for many countries or regions (such as the EU), the dependency and productivity concerns of an aging population might not be as pronounced as originally expected.

While this more nuanced understanding does not absolve us of the need to face the challenges of the aging society head on—particularly since many of the effects are not linked to dependency, but instead to issues like health care or inequity—it can help us assess and frame the size and urgency of the challenge and decide where to focus our efforts.

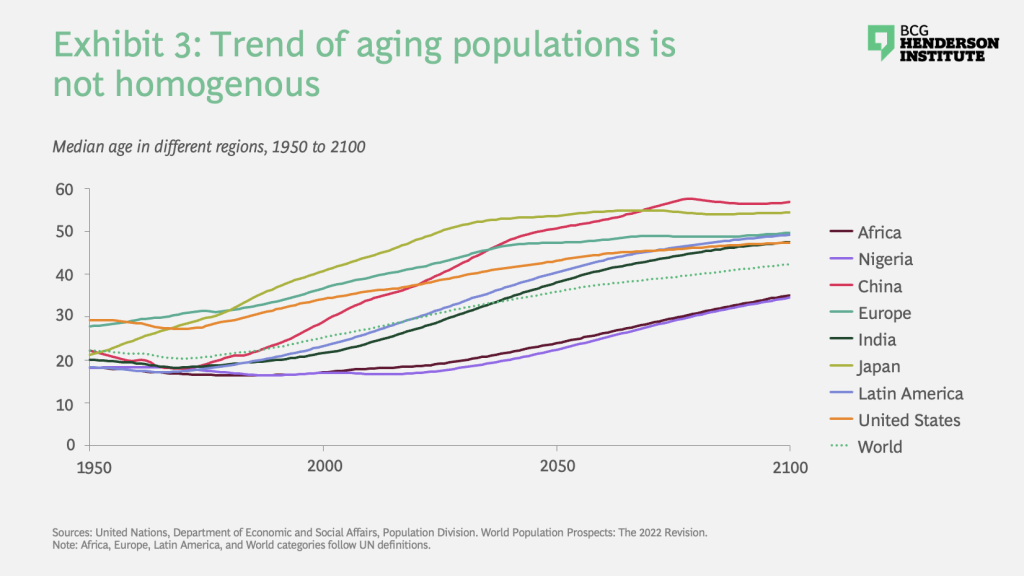

Aging and its challenges are not homogenous around the globe. Populations are aging worldwide, but this trend is not homogenous (see exhibit 3). Currently, aging is furthest progressed in Japan and Europe, but China is expected to overtake both in terms of median age before 2100. Meanwhile, populations of countries like Nigeria and others in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), Yemen, Afghanistan, and Pakistan remain significantly younger on average—though they are all predicted to see significant increases in median age. Underlying this data are differences in life expectancy. In SSA, life expectancy has increased by 9 years, to 60, in this millennium alone, but still lags behind many of the most developed parts of the world. Fertility rates have dropped by 1.1 since 2000 across SSA, but still hover at around 4.6 today.

In countries like Nigeria, then, the main demographic trend over the coming decades will not be population aging, but rather population growth—which itself is expected to present serious challenges for poverty reduction and the provision of governmental services, infrastructure, and housing, and to increase pressure on the environment. As such, any careful analysis should account for the heterogeneity of aging patterns.

Emerging elements of solutions for creating a flourishing aging society

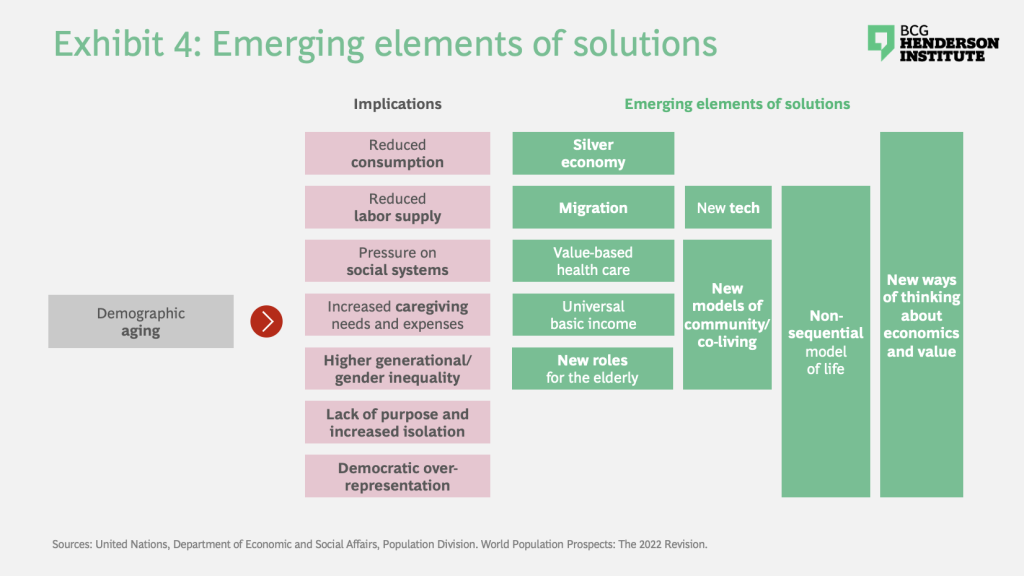

How can a society and economy continue to flourish in the context of an aging population? Below, we summarize emerging elements of a potential vision, arranged in ascending order of novelty and breadth of implications: from basic ideas like harnessing the power of migration or adapting products and services to an aging consumer base, to more speculative and far-reaching ideas, like abandoning the sequential model of life (see Exhibit 4, below, for a simple summary).

1. Migration as a talent gap solution.

The heterogeneity of global aging patterns creates one potential solution element: Migration. Workers can move to areas with labor shortages, which can also provide benefits to origin countries, such as reduced population pressure, increased remittances, direct investment, or development aid, and a transfer of skills and knowledge. However, countries of origin can also experience significant downsides, including the flight of human capital (“brain drain,” which has occurred in Romania) or a marked overall population decrease (which has happened in Bulgaria).

Executing on this solution is difficult in a world in which racial and religious tensions continue to be high in many regions, and in which protectionist tendencies are on the rise, making policies around immigration highly contentious. Public backlash to immigration reforms in Japan, primarily driven by concerns about effects on domestic workers, are a recent example.

Additionally, migrant workers have often been subject to reduced welfare, human-rights abuses, and increased risks of severe harm at work. International collaboration is needed to guarantee basic rights and welfare for such migrant workers and their families, possibly through the creation of a global social safety net. Finally, even with appropriate systems in place, migration can only serve as a stopgap, given the global nature of the demographic aging problem in the long run.

2. The silver economy.

One of the most common worries about the aging population is that it will lead to a contraction of consumption and the disappearance of markets. However, shifting demographics will also create new opportunities based on the needs of the elderly through what has been called the “silver economy.” For example, as the Japanese population aged, the domestic diaper market shifted from the traditional target group (parents of young children) to older adults, who used the products for incontinence control. Japan-based player Unicharm came to dominate this market while U.S.-based P&G exited—likely too early—upon observing that its traditional target group had diminished.

Given that wealth is becoming increasingly concentrated with the elderly, companies should be actively creating opportunities to provide new products and services to older people—with key sectors being assistive technologies, travel and leisure, health and other caregiving, financial services, and real estate.

3. Technology to improve productivity and personalize products and services.

Decreases in workforce productivity because of aging can be offset by technological innovation. Some advancements will increase the productivity of all workers, for instance, AI tools like Github’s co-pilot improving the efficiency of programmers. Other innovations may allow older people to engage in work they may otherwise have aged out of, for example, Hyundai Motor Group has developed an exoskeleton vest that assists industrial workers.

More radically, significant resources are being poured into overcoming the health effects of aging altogether, or at least substantially reducing them—even if for now, this still seems like science fiction. For example, Altos Laboratories, which seeks to identify cell rejuvenation techniques, recently closed the largest startup funding round in history at US$3 bn. Controlling the aging process could allow for maintaining productivity independent of chronological age.

Finally, AI is poised to support the customization of products and services to the particular needs of older people, for example, in healthcare and education. Both are crucial areas in an aging society, which will require lifelong reskilling and in which the elderly are likely to have very diverse patterns of consumption. However, in an age of increased loneliness and social polarization, we must be prudent that the increased use of AI does not lead to an addiction to chat bots, which may lure people in with easy sociability, but are unlikely to replace human-to-human relationships.

4. New ways of working and living for the elderly.

The decrease in productivity associated with demographic aging can also be counteracted by reimagining ways in which the elderly can contribute value to the economy. For example, given their experience, many older people could take on roles as advisors, mentors, and consultants. Other kinds of non-physical work, such as writing or editing, planning or designing, and coding may also be suitable for elderly workers. To support these possibilities, employers will need to rethink their hiring and on-boarding strategies, provide opportunities to support learning of relevant skills, and offer flexible or remote work arrangements.

Beyond work, society’s elder members may also be well-positioned to help meet the increased need for caretaking of both the old and the young—focusing on emotional as well as physical needs. An additional benefit of creatively reimagining roles for the elderly is that it may help them unlock a renewed sense of purpose and fulfillment.

5. New forms of community and co-living.

Multi-generational households have existed in many cultures for centuries, and are now becoming increasingly popular in developed nations, including the U.S. The benefits of multi-generational households for the elderly include increased financial stability and family companionship. Elderly members of these households can also provide important services in the form of childcare, social interaction, and emotional support. An alternative to this model (as well as to formally planned retirement communities) are so-called NORCs, or naturally occurring retirement communities. In these communities, which are increasingly common in places like New York City, older people attempting to “age in place” (for instance, in a set of apartment buildings) by attracting a range of health care and social services to support their lives.

A more creative way of organizing aging communities is the establishment of so-called “paradise zones”—an extension of the already popular concept of a retirement village. The idea is to create small cities designed to cater specifically to older adults, taking advantage of economies of scale by providing expansive elderly-friendly public transit or health monitoring services. Taking this idea to the next level, we could imagine “silver innovation zones” developing around these communities, in which academic, governmental, and private players come together to develop and scale new technologies and services to support the elderly.

An even more radical shift would be a model that explicitly competes with the traditional family unit, for example, by practicing care for the elderly (or for children) collectively, rather than within each family, thus reducing the burden of care commitments and providing enhanced flexibility. A variation of this kind of model is already practiced in many Israeli kibbutzim.

6. New models for careers and lives.

As lifespans extend, the traditional, sequential model of life—consisting of childhood, education, work, and retirement—may no longer be sensible, and alternative, non-linear models may become preferred. These may involve, for example, multiple and alternating episodes of education and career changes before retirement. Such ideas are described in Mauro Guillén’s recent book The Perennials. To enable these new models of life, we may need to reevaluate many of our existing societal and business systems, such as Japan’s inflexible work and promotion culture and employers’ strategies for recruiting and upskilling older employees.

More radically, with technological advancements like generative AI potentially poised to replace jobs in large numbers, it may be time to reimagine what living a meaningful life outside of work and career looks like—at any age. In a potential future where labor demand is reduced, this might result in a leisure-based economy, which is centered upon helping people to pass their time meaningfully, perhaps by providing educational and other personally impactful experiences.

7. New social and institutional policies and approaches.

To support the kinds of initiatives needed to adapt to the aging society, we need to consider new social and governmental policies and approaches. For example, supporting a non-sequential model of life may mean offering easier and cheaper access to education at different stages in life. It will also mean reassessing the design of social safety nets and, implicitly, the underlying intergenerational contract.

Governments will, of course, play a pivotal role in enabling these transitions. New policies to support the aging society will come in many different forms. They will include programs to encourage financial and digital literacy as well as life-long financial planning to bridge the financial and digital divides. As the demand for caretaking increases, government policies might also support flexible leave or the provision of social security credits for in-home caregiving. Moreover, it could mean new policies to support non-traditional family models, including childless couples, single parents, multi-generational households, and various forms of elderly communities. As we reevaluate the role and function of our social safety nets, governments will also need to consider whether self-financed retirement systems or more general social safety nets, like a universal basic income, will better support the aging population.

Given the scope of required policy changes and their interlinkages, there may indeed be a need for a clean-sheet, integrated approach to system design. A successful precedent for such an approach is e-Estonia: When Finland decided in 1992 to replace its analogue telephone exchange with digital connections, it offered the old system to the former Soviet state Estonia for free. Estonia declined, instead deciding to leapfrog this development by building its own extensive and modern digital network. Through a series of successful public-private partnerships and major investments, Estonia has now become a global leader in digital-first government.

Governments will need to become more adaptable in order to navigate the unpredictable and hard-to-influence demographic shift: They will need to move from a classical, planning-based approach to governance, which is predicated on a stable and predictable environment, to one that focuses on adaptivity—experimenting with new policies, creating strong selection mechanisms, and quickly scaling what works.

Finally, governments will need to assess and address the increased inequities that are likely to be produced by the aging society. For example, increased demand for caregiving is likely to disproportionately affect women, while migrant policies are likely to have a disproportionate effect on racial minorities and people from the Global South. Governments must find ways to address the inequities and imbalances that arise and work toward just treatment for all.

8. New conceptions of the economy, its goals, and our role in it.

The above measures may in turn require reconceptualizing how we think about economic progress. Indeed, one of the key drivers of the challenges associated with aging societies is the standard assumption that economic growth, measured in terms of changes in GDP, is the right goal to aim for. It is because of this assumption that contractions of consumption or labor supply are perceived as problematic. Moreover, since GDP only measures those goods and services to which we, as a society, have assigned a price, this leads to an undervaluation of things like caregiving services provided within a family setting. For the same reason, a pure focus on economic growth comes at the cost of natural ecosystems and our climate, which we accept harming (potentially irreparably).

An alternative framing of the economy, and its goals and metrics, may be necessary and possible. For example, adopting a measure of inclusive wealth—accounting for human, social, public, and natural capital—might induce corporations and consumers to price in their impact on our limited natural resources and for services rendered to one another. Caring for people and the planet could become part of the objective function, a good to be embraced and valued rather than an invisible externality or constraint.

As an example, consider the nation of Bhutan, which tracks its Gross National Happiness—an index that incorporates factors such as psychological well-being, health, education, cultural and ecological diversity, as well as living standards—to ensure that advancements in economic productivity are accompanied by social progress and environmental sustainability. The index, introduced in the 1970s, continues to be refined in terms of data collection and variable definition.

One important aspect of such a reconceptualization specific to our healthcare systems would be further embracing and operationalizing a value-based approach, in which healthcare delivery systems are organized to maximize outcomes for patients while minimizing the costs of achieving these outcomes. By assigning a value to healthcare outcomes, trade-offs become more explicit and resources can be allocated more efficiently.

Implications for businesses and their leaders

Corporations are already being affected by the demographic shift, which will ultimately create meaningful changes in all facets of business: Changes in labor supply and productivity will necessitate adaptations in hiring processes and workforce management; shifts in the consumer base will affect demand and unlock new pockets of innovation potential; differences in global aging patterns will necessitate rethinking geographic prioritization; and new societal challenges and inequities will reshape the public perceptions of the role of businesses in society.

As such, businesses will need to play a crucial role in developing and implementing the emerging solutions. Below, we outline five imperatives that business leaders should take to heart today.

Put demographic aging on the agenda. Demographic aging and its implications are not yet a part of the strategic agenda of most businesses. The dimension on which businesses have made the most progress is the inclusion of older workers, but even here, concerns of ageism still abound, and few businesses dare to make significant changes to how they hire and train workers, what flexibility they offer in terms of work hours or workplace, or how they will use technologies to support specific groups of workers. And crucially, given further shifts in family and life models associated with the demographic trend, businesses need to consider such changes not just in relation to their oldest employees, but to all workers. Beyond people matters, many firms will need to fundamentally reconceive their business models to meet or create new patterns of demand or to comply with new conceptions of the economy and what constitutes value.

All this requires, first and foremost, a mindset shift in which the issue of demographic aging is met with the same fervor that businesses have started to display toward other megatrends, like AI and climate change.

Calibrate the impact on your business. Demographic aging is not uniform across the globe, and neither are its impacts or the reactions from policymakers and society (for example, countries like Japan are struggling with migration, while Canada has embraced it). As such, companies need to take a de-averaged approach to identifying the impacts that will affect them—directly, as well as in their supply chains and business ecosystems—and the opportunities that will arise across the workforce, consumers, and broader society. Additionally, businesses should start regularly monitoring how these developments play out. They should consider, for example, how the composition of their target consumer group, employee base, and the recruitment pool is changing.

Shape the new reality. Sitting back, waiting for demographic shifts to play out, and adapting as they unfold is a recipe for being disrupted—as the example above of Unicharm and P&G in Japan indicates. Instead, businesses need to create new markets by proactively imagining and testing solutions that could entice a changing consumer base. For example, U.S. company Silvernest recognized the growing trend of older adults who have spare rooms in their homes and are looking for ways to generate extra income or seek companionship. It created an online platform that matches homeowners, typically older adults, with compatible housemates, who could be other older adults or younger individuals seeking affordable housing options.

Collaborate with policymakers. Governments will have to make meaningful changes to policies and social systems. Rather than merely anticipating these changes, companies should take the opportunity to shape them by collaborating with public agencies. Doing so will ensure they stay on the vanguard of change and are able to anticipate new rules and standards—as well as the risks and opportunities they will create—in a timely manner. Moreover, taking an active role will ultimately lead to better policies, because businesses can help governments road-test ideas as they are being developed and provide important feedback to the policy process. Businesses can also learn from one another in the scope of this shaping process, exchanging best practices.

Raise awareness. A key issue of demographic aging, like other slow-moving developments such as climate change and biodiversity loss, is that their impacts are not playing out quickly enough to be consistently present in the public mind. As French demographer Alfred Sauvy noted his 1957 work La Population, politics and the economy are the second and minute hands on a watch face, while demography—the hour hand—moves slowly. Yet, “the short hand of the watch is the most important, even if it seems immobile.” This is further complicated by an inconsistency of narratives related to demographic aging around the globe, stemming from different levels of progress on the aging curve.

To ensure that all stakeholders take steps proactively to embrace the opportunities and meet the challenges of demographic aging, businesses need to help raise awareness of the topic, anchoring it on the societal and political agenda. This does not imply CEOs should simply speak out on the issue of demographic aging. Rather, they should make noise through action: For example, announcing provisions for older workers, support for new life models, or new products and services tailored toward the elderly will attract public attention and inspire reactions from competitors and policymakers.

Demographic aging will shape society around the globe in the coming decades. To make sure it does not have deleterious consequences for humanity, or an unnecessarily painful adjustment period, we need to proactively adjust our institutional frameworks.

While the emerging solution elements provide inspiration for agencies and businesses about potential end states in which we have created a flourishing aging society, they do not yet tell us much about the transition process, which will likely produce surprising new challenges and interdependencies. As such, continually enhancing our understanding of the nuances of the challenge will remain crucial, as will enhancing the flexibility of governments and businesses to adapt to and shape the coming changes.

Further reading

Participants prepared written provocations related to their unique expertise in advance of the Meeting of Minds discussion. These were used to seed the conversation and enable focus on points of intersection, commonality, and debate across fields.

About the Meeting of Minds

The Meeting of Minds is a multi-disciplinary meeting of leaders in business and science discussing major issues in society and business, hosted by the BCG Henderson Institute. Previous meetings discussed topics such as the value of diversity, what we learned from the COVID crisis, and strategizing and managing on multiple timescales.